Kathleen Cande and Skip Stewart-Abernathy

Artifact of the Month - September 2018

Amidst discussions of lost crops and accompanying loss of income, the appearance of a series of boats on the bottom of the Mississippi River in West Memphis during the drought summer of 1988 was a bit of good news. Since the boats were on the Arkansas side of the river, they belonged to the state of Arkansas. The Arkansas Archeological Survey committed to documenting and excavating the remains of eight boats revealed in this low-water event. Survey archeologist Skip Stewart-Abernathy directed the project, and edited a book about it, Ghost Boats on the Mississippi, which can be found in our Publications catalog.

This type of unexpected find and the ensuing excavations are often called “salvage archeology.” With the boatwrecks site, the urgency was not only caused by fear of the water rising, but also the damage done by people digging around the wrecks and taking pieces away. In a salvage project, every effort is made to record and document as much as possible in a short period of time.

There were scores of visitors to the site during our work from late June through mid-August 1988. The Mississippi River was 40 feet below the normal top of its riverbanks. This exposed a long segment of sandy beach where the boat remnants lay. The two best preserved boats were a wooden model barge and several sections of a stern-wheel steamboat. Staff from the Arkansas Archeological Survey and trained volunteers from the Arkansas Archeological Society worked to excavate, photograph, and document the unusual finds. The model barge had been constructed from pine lumber, something that is rarely preserved on a terrestrial archeological site. Excavations of part of the steamboat crew cabins revealed wooden framing, a stool, and fabric from window curtains. There were tomato seeds preserved inside a glass ketchup bottle.

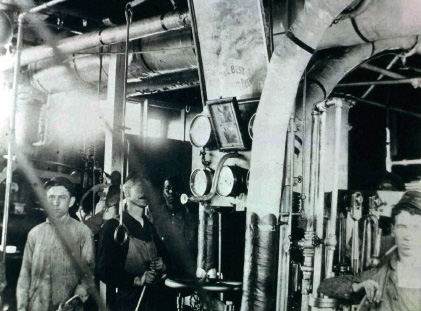

One of the most exciting finds was a brass steam gauge. It was in very good condition, and the manufacturer’s name was on the dial. It was found in an excavation unit near where the boiler would have been in the wreckage of the steamboat. It is an Ashcroft brand steam pressure gauge, manufactured by the L.M. Munsey manufacturing company of St. Louis, Missouri. Its trademark indicates that it was made according to a patent granted to the E. H. Ashcroft firm of Boston in 1876. An advanced version of the basic gauge design is still produced by Ashcroft today (Ashcroft 2018).

Although it was impossible to determine the name of the wrecked steamboat, we know that it sank in the 1920s because of maker’s marks on fire bricks from the boiler room. So the steam gauge was made well after the patent date. It may even have been used first on another steamboat and salvaged to be reused in this boat. After the excavations, the steam gauge was cleaned and conserved by the Memphis Pink Palace Museum staff.