Indians in the Old South

by George Sabo III France turned over administrative control of the Louisiana Territory to Spain in 1763, but relations between Indians, Euroamerican settlers, and governing officials remained much the same as they had been under the French regime. Despite continuing declines in population, the Indians of the Mississippi Valley were still a vital economic, political, and social force in the life of the region.

This mutually dependent relationship between Indians and Euroamericans changed when the United States acquired the Louisiana Territory in 1803. The United States wanted land for its own growing population. Unlike the earlier colonists, they did not need Indian alliances to ensure the integrity of territorial claims. Nor was Indian participation necessary for the expansion of plantation agriculture across the South. With the Louisiana Purchase, the status of Indians quickly changed from valued economic and political partners to a dwindling group whose presence on the land conflicted with United States plans.

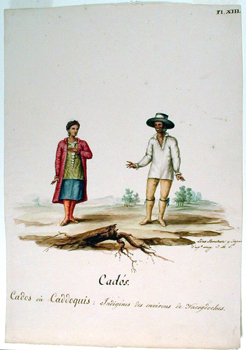

The influx of Indians from east of the Mississippi created many difficulties for Indians whose homelands were located west of the great river. In 1808, the Osages were forced to cede their lands in northern Arkansas and Missouri to make way for displaced Cherokees and Shawnees. The Arkansas Territorial government then forced Quapaws to leave their homelands along the lower Arkansas River and move onto Caddo lands farther south along the Red River. Unfamiliar with their new environment and hit by a series of floods, the Quapaws lost crops over successive planting seasons and became destitute. Some Quapaws determined to persevere in their Red River settlement while others decided to return to the Arkansas River. Neither group succeeded in establishing security. The Arkansas River group moved to Indian Territory in 1833 and joined a Creek community, while the Red River group was removed to another reservation. A year later, the federal government found that Wharton Rector, the agent in charge of their move, had led the Red River Quapaws to the wrong location so they had to move again. No compensation was made for lost homes, land improvements, and crops. Throughout the colonial era, the Osages managed a lucrative trade empire that controlled the movement of commodities between the Great Plains and major French and Spanish trading houses in St. Louis. This empire fell apart when the United States took control of northern Arkansas and Missouri. The region plunged into violence as immigrant tribes and white settlers fought the Osages for control of the land. Forced by government treaties to give up nearly all of their original homelands, the Osages in 1825 were moved onto a reservation in Kansas, where attempts to resume their former way of life were thwarted by the near extermination of buffalo at the hands of white American hunters.

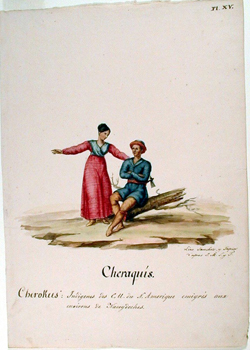

Removal of Osages and Quapaws from the central Arkansas River region made way for a large group of Cherokee immigrants, who took up residence in the Dardanelle region, near modern-day Russellville, after treaty negotiations with the federal government were completed in 1817. These “Western Cherokees” established a series of farming communities led by a group of strong Cherokee leaders including Duwali, Takatoka, Tolontuskee, and John Jolly. These communities pursued an agricultural routine much like that of their white American neighbors, growing corn and other crops on lands they tilled using horse-drawn plows. On the other hand, Indian social organization was based on traditional rules of kinship and community leadership. The Cherokees continued to perform traditional celebrations like the annual Green Corn ceremonies to renew social and spiritual relationships. In 1820, John Jolly succeeded in convincing the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions to send missionaries and teachers to Arkansas. From 1820 to 1828, Dwight Mission provided religious service and educational training for the thriving Cherokee community. Demands by white Arkansas settlers for access to their lands forced the Cherokees to cede the reservation in 1828. That year the community relocated to a new reservation farther up the Arkansas River in Indian Territory.

The new communities established in Indian Territory were intended as refuges where Indians could take up a new livelihood patterned after the rural agricultural ways of the dominant white American society. Support in the form of money, farming equipment, and seed stock was sent to the reservations, but much of this was diverted by unscrupulous Indian agents and other privateers. The U.S. government also passed a series of laws designed to eradicate vestiges of Indian cultural traditions. Circumstances grew even worse for Indians during the Civil War. Union troops held much of Indian Territory at first, but Confederate forces took control after 1861. A Confederate Indian army was drafted by General Albert Pike, an Arkansan appointed by Jefferson Davis to be the Indian Territory commissioner. Led by the Cherokee General Stand Watie, the Indian army (comprised mainly of eastern Indians who had been brought to Oklahoma during the Trail of Tears) harassed Union forces along the Arkansas River between Little Rock and Fort Smith. Many other Indians, including Caddos, Osages, and Quapaws, sought the protection of Union forces in Kansas. After the war ended, Indians returning to their reservations found their properties and improvements in a state of devastation. To make matters worse, U.S. Indian agents reduced federal assistance and seized additional lands in retaliation for the Indians’ “support” of the Confederacy. Once again, the Indians were left mainly to their own resources to pick up and start from scratch.

|

||||||||

|

|