Archaic Period Cultures: Holocene Hunters and Gatherers

8500-600 B.C.

by George Sabo III

Arkansas Indians responded to Holocene environmental changes during the Archaic era with new strategies for harvesting nature’s bounty. Population growth continued, and patterns of settlement and land use became more sedentary. Other cultural changes were part of the package.

A proliferation of flaked stone tools—including many kinds of projectile points and other implements used to cut, scrape, engrave, drill, and abrade or polish—testify to the increasing diversity of tasks and a desire for more specialized tools to accomplish them. Milling basins and grinding stones demonstrate the growing reliance on wild plant foods, which needed to be processed by removing their shells and husks. Bone fish hooks, harpoon heads, and net weights show the importance of fishing. Bone and antler needles and awls used for making tailored clothing have been found at a few sites, along with preserved examples of skins sewn with deer sinew thread. Other garments were made from woven plant fibers. Archaic Indians wore bone and shell bracelets, necklaces, pendants, and other adornments. Woven mats and baskets served a variety of needs.

|

|

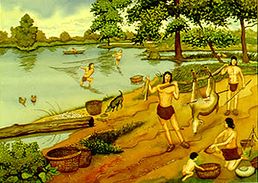

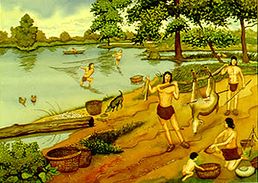

Archaic lifeways, by Dan Kerlin. Courtesy of the University of Arkansas Museum.

|

Preserved plant and animal remains provide direct evidence of the more diverse food getting economies. Deer was the most important game animal, providing meat and marrow plus antler, bone, hides, hooves, and sinew for the manufacture of other items. Turkey, opossum, squirrel, and rabbit were taken, along with fish, shellfish, and turtles. Plant foods, especially nuts and acorns, became an important dietary staple. Hickory nuts have a high fat content, which made them an important food for Archaic Indians whose active lifestyle required a higher intake of fat than lean animal flesh could provide. This broad spectrum food getting economy was in place throughout the Mid-South by 6000 B.C. Group choices and preferences gave rise to local variations in Archaic food-producing strategies.

Most Archaic communities followed a common settlement pattern first developed by their Dalton predecessors, featuring permanent base camps surrounded by a variety of special purpose sites. Archaic Indians built circular dwellings with light pole frameworks, bark-covered or mud plastered walls, and grass thatched or bark-covered roofs. Dwellings were dispersed among outdoor activity areas for food preparation, manufacturing, and other tasks. Men, women, and children ranged out from their base camps to nearby localities where they hunted, gathered wild plant foods, quarried stone or other materials for tool making, and collected wood for fuel and building needs.

|

|

Different styles of Archaic projectile points representing separate regional groups.

|

Over time, population growth gave rise to an increased number of Archaic Indian communities occupying an ever changing landscape. An interesting social phenomenon developed, in which settled communities began to use distinctive styles of dart points, basketry, and clothing to signal their identities. Archeologists believe that this use of material items to communicate social identities arose in response to growing needs to regulate interaction among groups living in close proximity to each other. Key to this use of material items is the concept of style, which we define as an appearance given to an object that is intended to communicate some form of information, such as individual or group identity.

One example of this phenomenon is seen in the development of the Middle Archaic period Tom’s Brook culture (archeologists named this culture after a tributary of the Arkansas River where the remains of this group were first recognized). These people lived in more-or-less permanent camps throughout western Arkansas, from the Arkansas River all the way south to the Red River, between 6000 and 4000 B.C. Like other Indians of the time, the Tom’s Brook people hunted with the dart and throwing stick, but they tipped the ends of their darts with a distinctive stone projectile point that archeologists call Johnson points. These points, with broad, triangular blades and heavily ground, straight-sided stems, were made only by Tom’s Brook people and are thus diagnostic markers of their presence on the landscape. After 4000 B.C., the occurrence of a different projectile print, called the Big Creek point, signals a new group of people in western Arkansas. Archeologists are unsure whether the Big Creek culture represents a development from the Tom’s Brook culture, or alternatively a new group of people coming into the region from elsewhere.

Climate changes after 7000 B.C. affected Archaic land use patterns. During the Holocene Climatic Optimum (also referred to as the Altithermal, Hypsithermal, or "Great Warming"), average temperatures rose as much as 4 °C and there were corresponding decreases in annual rainfall. This brought hotter, drier conditions to many mid-South localities that lasted until about 3000 B.C. Decreases in ground water and standing water, reduced vegetation cover, and erosion diminished the availability of both plant and animal resources in many regions, making life hard for Archaic Indians. Some areas, especially broad river valleys surrounded by sheltering uplands, provided better conditions, so Archaic communities began to concentrate in those areas.

|

Gathering seeds, by Dan Kerlin. Courtesy

of the University of Arkansas Museum.

|

With populations concentrated in the fertile river valleys, Archaic people met the challenge to feed themselves by increasing their use of seeds, grains, and nuts, which could be collected in season and stored for later use. At the same time, they began to alter the habitats surrounding their settlements. Clearing of vegetation around the village and foot traffic churned up the soil and exposed it to sunlight, which in turn attracted weeds and grasses that prefer disturbed areas. Many of these plants—including chenopodium, knotweed, sumpweed, maygrass, and little barley—provide abundant, highly nutritious seeds. Archeologist Gayle Fritz studies the process by which Archaic Indians began to alter the annual reproduction cycles of these species by weeding out smaller plants and sowing the stored seeds of large, prolific plants. These practices imposed selective pressures that favored plants with desired characteristics. In time, this selection led to the evolution of domesticated strains, not only of the above-mentioned species but also sunflower and several varieties of squashes. These domesticated plants had greater food value—but at a cost: they needed to be planted and tended by people in order to grow. Despite the requirement for human intervention, the expanded range of nutritious, storable plant foods, and the advent of gardening as a new food producing strategy, combined to form a more diversified food base that supported growing populations.

Another interesting new development was mound construction. At several sites across the Southeast, Archaic communities began to construct mounds of earth and shell, sometimes in clusters of a half dozen or more, as early as 5000 B.C. Marvin Jeter has studied Archaic mounds in southeastern Arkansas, dating to around 1200 B.C. These mounds do not contain burials or support buildings of any kind. Their placement on distinctive topographic features near local population centers suggests that they marked ritual places or community ties to a local territory. In either case, these mounds represent an early manifestation of a practice to which later Southeastern Indians devoted considerable time and effort—namely, shaping the local terrain to project social identities and community relationships directly onto the earth.

|

|

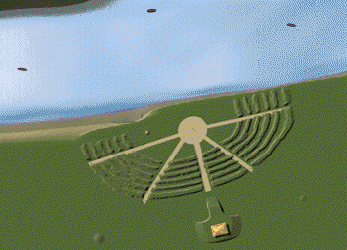

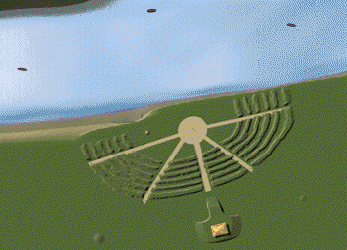

Artist’s concept of the Poverty Point Site.

|

The Poverty Point site near Epps, Louisiana represents the greatest Archaic period expression of this practice. Occupied between about 1600 and 1100 B.C. by as many as five thousand people, the site has numerous earthworks including several artificial mounds and six sets of concentric earthen embankments. The embankments, each about 6 feet high and 60 – 100 feet wide, form an immense semicircle some four thousand feet in diameter. These embankments supported an unknown number of pole frame houses. The largest mound, located at the “top” of the embankment complex, is a T-shaped earthwork that stands more than 60 feet high and measures almost 640 feet across along both its north-south and east-west dimensions. Once seen as a gigantic bird effigy, recent investigators like Jon Gibson and T. R. Kidder suggest alternative interpretations that are based, in part, on modern excavations that show the entire complex was rapidly constructed. One interpretation is that the mound and surrounding embankments represent the cosmological “earth island.” Another possibility is that the construction of these massive earthworks was itself a re-enactment of a primordial emergence event. These themes are prominent elements of historic Southeastern Indian mythologies, so if Gibson’s and Kidder’s suggestions have merit, the implication is that the roots of historic and modern Southeastern Indian cultures penetrate much more deeply into the past than we formerly suspected.

|

|

Poverty Point locust effigy beads.

|

According to archeologist Jon Gibson, a vast trade network emanating from Poverty Point drew the participation of dozens of communities in the central and lower Mississippi Valley. This trade generated a widespread distribution of artifacts made from a variety of imported materials, including shell, copper, and varieties of stone brought from considerable distances. These materials were used to make carved beads and figurines depicting humans, insects, animals, and birds. These objects represent an expansion in the use of artworks to symbolize relationships between human and nonhuman beings.

The Poverty Point site was abandoned around 1100 B.C. Trade links connecting regional communities came to a temporary halt. Recent studies by T. R. Kidder of the impacts of global climate changes suggest that the onset of cooler, wetter conditions played a role in these events. Severe flooding throughout the Mississippi Valley may have reduced fish harvests on which Poverty Point people depended. Many communities responded by abandoning long-occupied settlements, including the Poverty Point site, to relocate in areas where other food-getting activities were still reliable.

|

|

Poverty Point figurine.

|

The Archaic era leaves behind an interesting record of important cultural achievements. New strategies for harvesting an increasingly wide range of animals and plants supported growing populations and permitted many communities to become increasingly sedentary. Stylistic differences in material items emerged as a new way for groups to project their social identities. The environmental consequences of sedentary living along with the need to expand food production led to the domestication of several indigenous plant species and the advent of gardening. Increasing complexity of community organization prompted a variety of social experiments culminating in the Poverty Point culture and its innovations for organizing human labor to build monumental earthworks and manage the regional distribution of valued trade goods. Artistic representations in a variety of media, from portable artifacts to large mounds, symbolized relationships connecting humans with nonhuman animal and spirit communities. Elaboration of these trends produced the cultural manifestations of the subsequent Woodland Era.

Further Reading:

Fagan, Brian

2008 The Great Warming: Climate Change and the Rise and Fall of Civilizations. New York, Bloomsbury.

Gibson, Jon L.

2001 The Ancient Mounds of Poverty Point. Gainesville, University Press of Florida.

2006 Navel of the Earth: Sedentism at Poverty Point. World Archaeology 38:311-329.

Kidder, T. R.

2006 Climate Change and the Archaic to Woodland Transition (3000-2500 Cal B.P.) in the Mississippi River Basin. American Antiquity 71(2):195-231.

Schambach, Frank

2006 Tom’s Brook Culture. The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture. Encyclopedia of Arkansas Link

Trubitt, Mary Beth

2006 Archaic Period. The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture. Encyclopedia of Arkansas Link

|