|

First Encounters

Hernando de Soto in the Mississippi Valley, 1541-42 by George Sabo III The Mississippian Indians living in Arkansas and the mid-South experienced their first encounters with Europeans when the Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto entered the Mississippi Valley in 1541. Soto sailed in 1539 from Cuba to Tampa Bay along the west coast of the Florida peninsula. From there, he set off on a four-year exploration of the interior Southeast. His goals were to establish Spanish claim to the lands he explored, impose dominion over native communities, and seize gold and silver as he had done years earlier in Middle and South America. Soto died before his expedition ended. He established no lasting Spanish claims, his army inflicted severe harm on many Indian communities while conquering none, and he discovered no gold or silver among Southeastern Indians. The bedraggled remnants of his army escaped down the Mississippi River to Mexico in 1543.

These actions brought varied Indian responses. Some, curious to learn more about these strange visitors and their odd but intriguing possessions, welcomed the Spaniards despite the obvious risks. Others, who had already heard more than they cared to know about Soto’s cruelties, either abandoned their villages as soon as the Spaniards drew near, or set ambushes hoping to steer Soto’s force in another direction. This tactic seldom worked. Many groups had no forewarning of Soto’s approach and were surprised by the Spaniards’ sudden arrival. These groups, for the most part, were isolated from their neighbors by geographical or language boundaries.

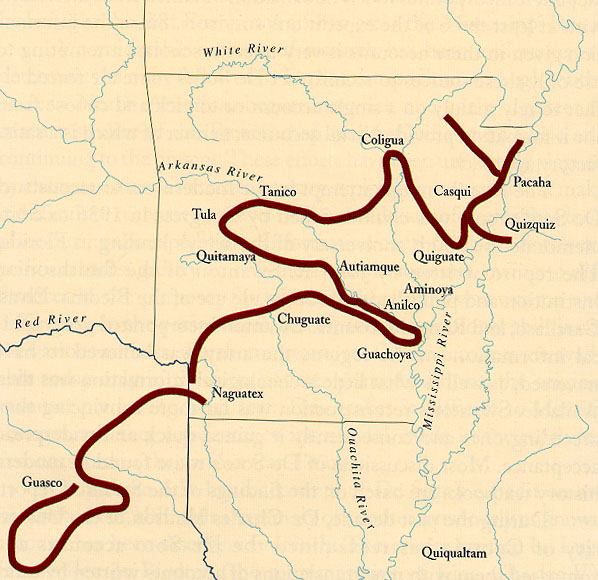

The chiefs of Casqui and Pacaha attempted to secure alliances with Soto by offering him marriage to Indian noblewomen. Intent on pursuing his quest for gold, Soto declined these offers and instead sent groups of soldiers to explore the nearby countryside. Finding nothing of interest, the army traveled south along the St. Francis River until they reached the province of Quiguate. The main town of this province was said to be the largest of all the fortified, agricultural towns the Spaniards visited in the Mississippi Valley. There they learned about another province, called Coligua, located in mountainous lands to the northwest. Since gold and silver are often found in mountainous regions (though not in the Southeastern United States), Soto pushed on to that province, crossing wet, uninhabited lands for a week before reaching the “River of Coligoa” (the White River near modern Batesville) along the eastern edge of the Ozark Mountains. The Coligoa Indians had not expected the Spaniards, which suggests there was no regular communication between their area and the Mississippi Valley. But neither did these Indians possess any gold. From Coligoa the Spaniards marched in a southwest direction, passing through several more provinces before entering the Arkansas River Valley. There, they found the town of Tanico (probably another Tunica community) in the province of Cayas. Cayas was a well-populated, agricultural area, but here the Indians lived in scattered farmsteads that were very different from the large fortified towns of the Mississippi Valley. Modern archeologists believe that the province of Cayas may have been located in the Carden Bottoms area, where excavations by Skip Stewart-Abernathy documented Indian settlements dating to the sixteenth century. From Cayas, the Spaniards continued up the Arkansas River (their “River of Cayas”). They entered the northern Ouachita Mountains south of modern Fort Smith. Tanico guides led them to the Tula Indians, whose language the Tanico Indians did not understand. Modern scholars believe the Tula were the ancestors of historic Wichita Indians who spoke a Caddo dialect. The Tula Indians used long lances to hunt buffalo, which proved remarkably effective against the charging Spanish cavalry. Both sides suffered significant losses in their battle, but Soto took no gold and precious little food.

With the prospect of cold weather and the hunger of his men and horses worsening every day, Soto led his forces back to the Mississippi Valley, to the main town of Autiamque. There they endured the hard winter of 1541-42, during which their translator, Juan Ortiz, passed away. From that point on, communication with the Indians grew increasingly difficult. In the spring of 1542, Soto moved his army to the town of Anilco. This is probably the Menard-Hodges archeological site along the lower Arkansas River. The town’s residents fled just before the Spaniards arrived. While the Spaniards were there, the Indians frequently returned at night to steal back their corn. Finding insufficient food at Anilco, the Spaniards moved to Guachoya, located along the Arkansas River just above its confluence with the Mississippi. Soto sent out a cavalry detachment, hoping they would discover a route to the sea, but they returned a few days later, having traveled in circles through swamplands. Growing increasingly alarmed at the plight of his army and his failure to find gold, Soto sent an Indian messenger to a powerful chief who lived farther down the Mississippi, demanding that the chief present himself and bring along samples of his province’s most valuable riches. The chief sent the messenger back, saying that he would comply only when Soto dried up the great river. This rebuke sent Soto into a rage. He ordered a brutal attack upon the unsuspecting people of Anilco. Hundreds of men, women, and children were so horribly slaughtered that even many of the Spaniards were shocked. Soto, fallen ill with fever, died a few days later. To conceal his death, his companions wrapped his corpse in blankets and slipped it into the Mississippi River.

The Soto expedition’s chroniclers produced the first eye-witness accounts of Mississippian Indian societies in the sixteenth century. Yet, these accounts raise as many questions as they answer. Who were the Indians mentioned in the Soto accounts? Groups such as the “Chicazas” and the “Tanicos” can be linked to the Chickasaws and Tunicas mentioned in later European accounts. But what about the Indians of Aquixo, Casqui, Pacaha, Anilco, Coligoa, and other “provinces” whose names fail to appear in later historical records? Who were those Indians? Archeologists and historians have made some headway in answering this question and have determined, for example, that the Indians of Quizquiz were probably Tunicans and the Tula and certainly the various groups in the Red River Valley were Caddoan speakers. The identity of many others remains a mystery. The impacts of Soto’s expedition on Mississippi Valley Indians must have been devastating, as communities were attacked, plundered, and disrupted in a variety of ways. Here, too, many questions remain. Soto’s army certainly inflicted much harm on the Indians, but climate reconstructions by dendrochronologist David Stahle show that the mid-sixteenth century was also a time when severe and prolonged droughts prevailed, which added a separate level of stress on Indian communities. It is very likely that the compound effects of the Spanish presence and unfavorable climate changes wrought the most lasting effects.

For example, Indian depopulation during the era of first encounters is often attributed to the introduction of European diseases against which Indians had no immunities. Did Soto’s expedition introduce such diseases? Biological anthropologists Barbara Burnett and Katherine Murray suggest that by the time Soto reached the Mississippi Valley, his army probably had long rid itself of potent germs and viruses. But they also acknowledge that Indian population declines did occur in the Mississippi Valley. They attribute the cause of those declines to cultural stresses linked to interaction with the Spaniards and dietary stresses resulting from crop losses. These two factors sufficiently reduced birth rates among young Indian women to result in overall population declines. Other topics raise similar debates: What impacts did the introduction of Spanish trade goods have on Indian communities? To what extent did Soto’s expedition result in population movements and changes in relations between groups that were formerly allied or previously engaged in hostilities against each other? In what ways did the arrival of Europeans alter Indian views of the world? We continue to search for answers to these questions, but one conclusion is certain: when the next set of Europeans entered the Mississippi Valley at the end of the eighteenth century, they observed a profoundly different cultural landscape.

|