|

Indians Today

by George Sabo III Modern American society is comprised of many “sub-cultures” or ethnicities. There are people who trace their roots to African nations, the Middle East, India, China and Japan, Indonesia, England and Ireland, other European nations, Mexico and South America, and the Pacific Islands. We are truly a nation of immigrants. But most of us are late-comers compared to American Indians, who represent hundreds of ethnicities tracing their presence in North American back to time immemorial.

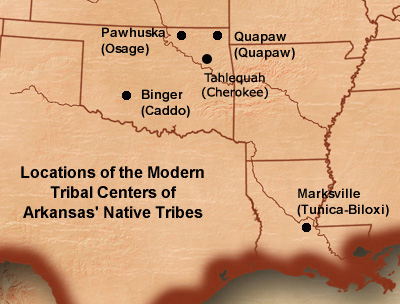

Some American Indians are your neighbors, enjoying occupations as doctors, lawyers, teachers, and workers in numerous manufacturing and service industries. Other Indians live in rural areas that once were part of nineteenth century reservations. In some of these areas today, the population is largely comprised of Indians who pursue agricultural livelihoods much like those of other rural Americans. Modern descendants of Arkansas Indian nations—Caddos, Cherokees, Osages, Quapaws, and the Tunica/Biloxi—live all over the United States but most reside in Oklahoma and Louisiana. Each of these nations maintains an administrative center in Oklahoma where their government offices are located. The Caddo Nation complex is located near Binger; the Cherokee Nation is headquartered at Tahlequah; the Osages are in Pawhuska; and the Quapaw Tribal Center is in Quapaw. The Tunica/Biloxi headquarters are located in Marksville, Louisiana.

Tribal governments offer a variety of programs to assist community members. Most Arkansas Indian governments operate a range of federally assisted programs for their communities, including Head Start/child education, adult education and vocational training, elderly health and nutrition, housing, legal aid, medical, police, social services, and transportation. Funds from other sources, including gaming receipts, are used to support other ventures. The Caddo Nation, for example, runs a small bison ranch on its Binger complex. They also operate a Caddo Heritage Museum which offers exhibits, educational programs, and library services. The Cherokees are building a new health center in Muskogee, Oklahoma, and they also provide language and traditional skills classes at a variety of locations including public schools in northeast Oklahoma. An on-line Cherokee language class and news podcasts are available on the Cherokee Nation website. The Cherokee Nation also offers a college scholarship program for its students. The Tunica/Biloxi run a museum at their tribal center that offers state-of-the-art artifact conservation services, and they operate a financial assistance program for qualifying home buyers.

Tribal museums and cultural centers play an increasingly important role in this process, providing new uses for ancient artifacts and historical documents. These materials—typically associated with the studies of archeologists, anthropologists, and historians—can also put modern Indian communities directly in touch with their heritage. As tangible symbols of ancestral accomplishments and experiences, artifacts and documents offer unique prospects for educational enrichment, cultural appreciation, and modern artistic expression. In recognition of the many values of heritage materials, modern Indian communities are strongly committed to implementing the provisions of the Native American Grave Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990. NAGPRA establishes a cooperative process between Indian nations and museums and federal agencies through which cultural materials including human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and emblematic objects of cultural patrimony can be returned to descendant groups, including culturally related tribes. Caddos, Cherokees, Osages, Quapaws, and the Tunica/Biloxi tribe all have NAGPRA programs for repatriating archeological and historical materials. In many cases, arrangements are worked out whereby museums and federal agencies continue to maintain repatriated collections on behalf of the tribe, though these materials are now available for tribal programs as well as for scholarly research. Another result of NAGPRA repatriation efforts is the development of closer relationships between Arkansas Indians and the scholarly community. Indian communities are beginning to play a more active role in archeological, anthropological, and historical research projects. This broadens the scholarly field of inquiry and provides a wider range of ideas and perspectives against which evidence and information can be evaluated. At the same time, closer engagement with the work of scholars enriches the Indians’ connection with their past. Indians and scholars both benefit from this new relationship, and Arkansas Indians gain another way to maintain ties with the lands their ancestors once occupied.

|