|

The Mississippi Period: Southeastern Chiefdoms

A.D. 900 - 1541 by George Sabo III Archeologists use the term "Mississippian" to refer to cultural developments in the Southeast between A.D. 900 and the 1539-1543 Spanish expedition led by Hernando de Soto. This was a time of expansion: population and town and villages numbers increased, as did the extent of agricultural production. Some communities numbered in the thousands, and tens of thousands of people lived at the Cahokia site near modern St. Louis.

Indian communities in many parts of the Southeast turned from mixed economies to agricultural economies between A.D. 900 and 1200. From A.D. 1200 on, corn, beans, and squash were the staple crops in many areas. Corn, which can yield abundant harvests with simple agricultural techniques, is deficient in lysine, an amino acid that humans require. Meat, fish, and some plant foods including beans contain lysine. Indian stews mixing corn, beans, and squash with bits of deer or turkey meat or fish provide a nearly complete nutritional complex. While most Mississippian Indians were farmers, archeological evidence indicates that some people specialized in other occupations. For example, Ann Early studied pre-contact salt making at the Hardman site in southwestern Arkansas. Here, artesian springs bring briny water to the surface from salt deposits deep below the ground. The briny water was boiled in specialized clay pans placed on rocks over large hearths. The residue was packaged in skins or pottery vessels for trade to communities lacking access to natural salt sources. Salt is an important nutrient that must be added to diets based mainly on agricultural produce.

Chiefdoms are unstable forms of society, given the inherent competition between communities and their leaders. In the Mississippi Valley, competition over agricultural lands frequently led to warfare between groups. Warfare among Southeastern Indians was very different from European warfare with its ordered ranks of soldiers facing off across open fields of battle. Indian fighting generally consisted of skirmishes, in which small groups of warriors struck quick and damaging blows. This inevitably produced a retaliatory attack. The overall result was endemic violence, though on a limited scale, and shifting alliances among neighboring towns and villages.

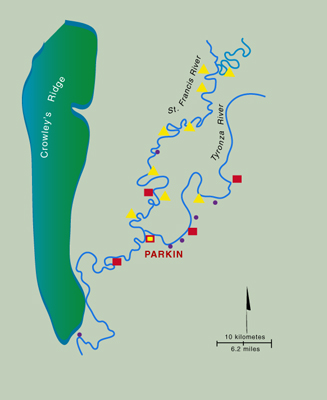

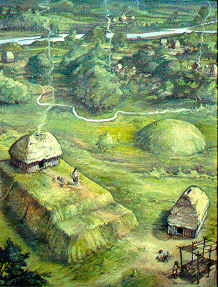

Community patterns separated common households from elite residential compounds within the Nodena and Parkin towns. Smaller satellite villages surrounded these towns. During times of warfare or strife, the regional population took shelter in the fortified towns. People also gathered at the larger towns for community rituals and ceremonies. In historic Southeastern Indian towns, such rituals were performed to renew and reaffirm relationships between humans and the spirit world.

The Parkin site is preserved today as part of Parkin Archeological State Park. Additional information about the Nodena site is available at the Hampson Archeological Museum State Park. Be sure to visit the Virtual Hampson Museum, a state-of-the-art website where you can view 3D images of Nodena phase ceramic vessels, tour a 3D visualization of the Upper Nodena village, and learn more about the Nodena people and their place in Arkansas history. Another type of agricultural chiefdom developed among the late prehistoric Caddo Indians in the Red River Valley in southwest Arkansas and adjacent parts of Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas. Ann Early and Frank Schambach study Caddo landscapes consisting of individual temple mound sites surrounded by dispersed family farmsteads. There is no evidence of fortification or of community field agriculture. Instead, scattered family farmsteads each had their own dwellings, granaries and other facilities, crop fields, and wood lots. Houses were circular in shape and entirely grass thatched, built on frameworks of tall upright posts drawn together at the top. Seventeenth century Caddo Indians were still building them, and European witnesses described them as resembling tall, grass-covered beehives. The compounds of Caddo leaders were distinguished by the presence of one or more platform mounds supporting temples and mortuary structures. Like their contemporaries in the Mississippi Valley, some Caddo leaders were able to extend authority over the leaders of neighboring communities, building hierarchically organized, multi-village chiefdoms. Unlike their Mississippian counterparts, Caddo leaders did not manage the economic resources of their communities. Production of essential goods was under the control of individual families, who provided for the material support of their leaders. Caddo ceremonialism also involved unique ways of maintaining and celebrating relationships with ancestral and spiritual communities.Much of what we can learn about the expansion of social ranking in Mississippian societies comes from the treatment of the dead. The locations of burials and the kinds of funerary objects interred with the dead show that Mississippian social distinctions surpassed the status differences represented in Woodland era burials. Highly ranked persons were given special grave sites, such as mortuary buildings on the surfaces of platform mounds. Elaborate funerary objects signifying elite status often accompanied the remains of these individuals. In some cases, the remains were later reburied, along with the funerary objects, in nearby earthen mounds. One of the most spectacular examples of this practice is the so called Great Mortuary at the Spiro site in extreme eastern Oklahoma, just a few miles west of Fort Smith, Arkansas. Here, the remains of numerous individuals representing many previous generations were reburied beneath a conjoined, three peak mound. The incomplete remains of several individuals were laid to rest on cedar pole litters, covered with countless shell beads, embossed copper plates, engraved conch shells, well made and elaborately decorated pottery vessels, bows and quivers of arrows, polished monolithic (i.e., blade and handle all of one piece) stone axes and maces, and other offerings indicative of high devotional value. Many funerary items from the Spiro site were decorated with motifs representing the local expression of a ceremonial complex that drew participants from a wide area. Communities from the Atlantic and Gulf coasts to the edge of the Great Plains to as far north as the Great Lakes took part in this ceremonial complex, which originated around A.D. 900 near the Cahokia site. Cahokia, in the following centuries, became the largest city and ceremonial center north of Mexico. Ceremonial items made around Cahokia were decorated using a specific set of design criteria called the Braden style. Wide distribution of Braden style artifacts across the Southeast by A.D. 1200 shows how the style spread outward from the Cahokia area in the centuries immediately following its origin. After A.D. 1200, regional styles derived from the Braden style show up, especially around major centers at the Spiro site in Oklahoma, the Moundville site in Alabama, the Etowah site in Georgia, and the Lake Jackson site in Florida.

Not all Mississippian people relied on corn, beans, and squash. Many parts of Arkansas and the mid-South were unsuitable for intensive field agriculture. This was true, for example, in the lower Mississippi Valley region (extending into Southeastern Arkansas), where a civilization called the Plaquemine culture thrived mainly by hunting, gathering, and fishing. Archeologists believe the Plaquemine people were the ancestors of historic Tunica Indians. Across much of the Ozark and Ouachita mountain regions, other small scale hunting, gathering, and gardening communities persisted throughout the Mississippian era. Different orientations to the land and its resources did not prevent these groups from maintaining economic and ceremonial ties with their agricultural neighbors in adjacent regions. In the western Ozark Highlands, for example, Marvin Kay and George Sabo studied mound centers constructed by local Mississippian communities. Mortuary ceremonies at these mounds celebrated connections between the living community and ancestor spirits. Details of mound construction and burial practices indicate that the Ozark communities were affiliated with Arkansas River Valley groups that built and used the Spiro site. The presence of various non-local raw materials at Ozark mound centers further suggests that these sites served as nodes in the long distance trade networks that supplied the exotic materials to manufacture the specialized funerary objects and prestige goods seen in abundance in the Mississippian “heartland” areas. These connections made it possible for many late prehistoric communities, regardless of their size and location, to participate in pan-regional religious systems and other widespread traditions of Mississippian culture. Some Mississippian chiefdoms persisted into historic times. Most well known are the Natchez and Caddo chiefdoms encountered by Spanish and French explorers in the early 18th century. By that time, however, most mid-South and Southeastern societies were less complexly organized than their predecessors. The environmental consequences of population concentration and overfarming played some role in these changes. Soil nutrients and timber resources were depleted. David Stahle’s studies of tree ring data collected from across the Southeast indicate an extensive drought in the late 15th century, which added to the stress on an agricultural system lacking large-scale irrigation. Warfare between groups and transmission of Old World diseases moving ahead of direct contact with Europeans might also have contributed to declines in some areas. Despite these unfortunate events, the long trajectory of American Indian history created a legacy in the land that influenced subsequent European exploration and settlement in the mid-South. The economic opportunities that 17th and 18th century European explorers and settlers found in the Arkansas region were very much the product of the long term adaptations of earlier Indian communities.

|