Rock Art Documentation in Arkansas: By Introduction A major initiative of the Arkansas Archeological Survey's rock art project was to develop a database of rock art sites. To begin, we compiled existing data on Arkansas rock art from various sources, including the state site files, published and unpublished reports, and field notes. Since the information on rock art had never before been systematically organized, we needed to develop a set of data recording forms. These were based on forms originally designed by Loendorf & Associates for recording rock art in the American West. Linda Olson used our draft forms in May 2000 for a detailed rock art documentation workshop at two sites in Petit Jean State Park, as part of an Arkansas Department of State Parks and Tourism project funded by a grant from the Arkansas Natural and Cultural Resources Council. In fact, we tried several draft versions of our forms to transcribe data from existing sources and to record new data in the field before arriving at a suitable format that would ensure standardized documentation and facilitate encoding of rock art data into the Survey's AMASDA computerized site record system. The new forms supplement the primary AAS site record forms. Part of our process to develop the forms was a four-day field trip in June 2001, during which a crew from the Arkansas Archeological Survey (Mike Evans, Jerry Hilliard, Jared Pebworth, Larry Porter, George Sabo III, and Michelle Berg Vogel) documented rock art at seven previously known sites in Petit Jean State Park. The park has several rock art sites within its boundaries, ranging in size from Rockhouse Cave, a very large shelter with over 100 images, to small shelters that contain only one pictograph. This report provides a brief discussion of our fieldwork procedures, and acts as a useful guide for other research teams using the Survey's new rock art record forms. Copies of the forms and instructions can be downloaded from the Resources section of this website. Part One: Site Selection and General Procedures The June fieldwork began with a records search in the Arkansas Archeological Survey Registrar's Office, which generated a complete list of sites in the Petit Jean State Park. We selected several sites as candidates to test out our new forms. Rock art at these sites had never been systematically documented. Each site contained less than a dozen rock art elements, a number we felt we could handle for testing the new forms in a reasonable time frame. Proximity to hiking trails was a second consideration, since we planned to map the sites and surrounding terrain with surveying instruments that we had to carry in on foot. We then made a day trip to the park to make a final determination of how many sites we could document in one week's time.

While each site offered a different challenge, we followed a basic set of procedures. We first produced detailed maps of the shelters and their surrounding terrain using a Topcon Electronic Total Station. Then we plotted on these maps the locations of individual rock art elements. We also took basic dimensions of each site with a measuring tape: shelter length along the dripline; shelter depth at the midpoint from the back wall to the front edge of the dripline; and shelter height from ground surface to the tallest part of the ceiling at the dripline. Following the mapping, we filled in site and rock art details on the new recording forms. Part 1 of the form covers basic information such as site type and dimensions, identity of the recorder(s), and ambient light and weather conditions at the time of recording. Part 2 provides for a general description of the rock art at the site as a whole, and contains a series of checklists to ensure that the data will be consistent and complete for all sites. Parts 3 and 4 have space for additional comments and interpretations and a photo log. Part 5 is for details of individual rock art elements and panels using a combination of checklist, verbal, and pictorial descriptions. One person can complete the form but we found that two people work more efficiently. The advantage is not only in terms of speed but also in the quality of the resulting information. One person taking measurements and working close to the rock art can often see things that a recorder standing farther back cannot see. Likewise, the recorder has a different perspective and can often detect markings that are not obvious close up. Detailed recording of elements and panels using Part 5 of the form followed a specific procedure to fit the database requirements of our project. First, we assigned consecutive numbers (1–n) to all rock art elements observed at a site. Next, we also numbered consecutively any panels that were recognized. The criteria we used to define panels were 1) the presence of two or more elements together on a uniform rock surface, or 2) spatial proximity of elements intentionally joined together in an apparent group or thematically related. The images comprising each panel also retain their previously assigned element numbers. After recording element and panel data onto the forms, we took black and white photos, color slides, and digital images of all elements and panels, using a scale bar in each image. (The scales we use are available through IFRAO at http://www.cesmap.it/ifrao/ifrao.html). Part 4 of the rock art form is a field photo log. Part 5 includes space for a quick sketch of each rock art element and checkbox notations linking that element back to the photo log and to other graphics created in the field, such as drawings or tracings. We found it helpful to add a sketch on graph paper showing the spatial relationships of individual elements at a site or within panels. We next made tracings of selected rock art elements. Ideally tracings are made of all elements at a site, but sometimes this is not possible. Some elements cannot be traced because of inaccessible location, because they are too faded to see the pigment through the tracing film, or because the rock surface on which they occur is unstable. Time may also be a factor. In general, we traced as many elements as time allowed. For very faded elements, we made sketches instead.

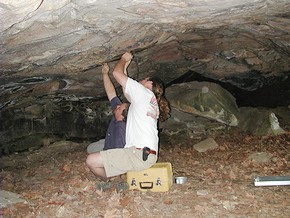

Tracings are a valuable tool because they provide full-scale representations of the rock art and sometimes more precise depictions of the relationship between elements at a site than can be achieved through photography or drawings. If we think of rock art elements as artifacts, tracings provide a handy means to take these artifacts back to the lab. The equipment we use for tracing includes clear acetate (Mylar) film, duct tape, colored Sharpie markers, and adhesive tape. Tracings should always be executed with the utmost care, because the procedure requires contact with the rock art and surrounding surfaces. If the rock art at a site is particularly delicate, tracing may not be appropriate. Most of the rock art at Petit Jean State Park is relatively stable and could be traced without causing damage. Even so, care must be taken not to affect the rock art in any way. Tracings should be executed as swiftly as possible while still endeavoring to create an accurate image. The acetate film should be affixed to the rock surface using as little tape as possible. It is very important to use an adhesive that does not leave a residue and tape NEVER should be applied directly over a rock art image. We found that duct tape held the acetate film securely in place without leaving a residue. The most time spent on a single tracing during this project was about three hours. We were able to limit the time spent on large tracings by having more than one crewmember work together. Different colored pens can be used to depict different aspects of the rock art and the surrounding surface. For example, we used a black pen to trace the actual rock art pigment, a blue pen to trace natural features in the rock, a red pen to trace cracks or crevices, and a green pen for lichen. A color key was added to the label on each tracing. The label also included basic information such as site number, rock art element and panel numbers, and date and names of crew members working on the tracings. One problem with tracings (as well as sketches and drawings) is the tendency people sometimes have to embellish an image by filling in lines that are not really there. To avoid this, we strictly followed (and recommend) a basic guideline of tracing or stippling only over visible pigment. This avoids the impressionistic or imaginative additions and transformations that have sometimes brought confusion to the general knowledge about rock art sites. Tracings, sketches, and scale drawings are useful complements to photographs and slides, which can be strongly affected by light conditions, shadows, and angles. Each type of pictorial record adds something unique to the database. The AAS Rock Art Survey in Petit Jean State Park Day 1

In May 2000, trained volunteers thoroughly documented the rock art at Indian cave (3CN17) as part of the Arkansas State Parks conservation effort. They did not map the site, however, so our first task on Day 1, after driving to Petit Jean State Park from Fayetteville, was to produce a detailed map of this site and its surrounding topography using the Total Station. In the process, we mapped in the locations of each previously recorded rock art element in the shelter, and discovered two additional elements. This is fairly common during rock art fieldwork; elements are often overlooked due to weather and lighting conditions. Faded elements are difficult to see. It may take multiple visits by several different observors before all the rock art at a site is discovered. Day 2

We spent our second day in an area of the park where three rock art sites are clustered in a hollow; we documented all three in a single day. One site, 3CN155, is a small shelter on the east bluff line of the hollow. The other two sites, 3CN125 and 3CN157, are on the opposite side of the hollow across a small drainage. We set up a mapping station in the middle of the drainage to map all three sites and the surrounding area. Two crew members spent approximately six hours completing this task. 3CN155 is a small shelter with a low overhang (6 m long, 3.2 m deep, and 1.55 m high). The rock art at the site consists of four red pictograph elements: two sunburst images and two plant-like images. The sunbursts are outlined figures, and the plant-like images are solid. The elements are next to each other on the same rock face (on the slanted ceiling toward the front of the shelter). At this site, we did not assign a panel number in the field, though it is possible that one or two panels could be defined. We made a sketch on graph paper showing all the elements in relation to each other, and two tracings: one of elements 1 and 2 (a sunburst and a plant-like image) and another of elements 3 and 4 (the second sunburst and plant image).

Elements 1 and 2 were in similar condition, more distinct and less faded or damaged than elements 3 and 4. Our impression was that perhaps elements 1 and 2 were executed at or around the same time, while the same could have been true for elements 3 and 4. Our grouping for the tracings reflects this impression. Recording at this site took between one and two hours, and each of the tracings took 45 minutes to one hour for one individual to complete. The location of the rock art in 3CN155 made tracing the elements a challenge. The shelter is low and the rock art is on a slanted part of the ceiling near the front. A large tree just in front of the area containing the rock art added to the difficult setting.

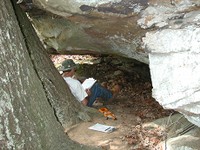

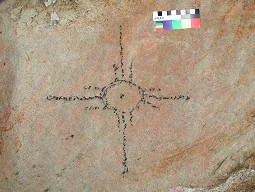

The second site, 3CN125, is another small, low shelter (13.6 m long, 5.2 m wide, and 1.75 m high) with both clear and faded rock art elements. Unlike 3CN155, the rock art at this site is mainly located on the ceiling inside the shelter, so it is not immediately obvious to a visitor. The most prominent element is a zoomorphic (animal) image often interpreted as a beaver because of what appears to be a wide flat tail. Due to the low ceiling, light conditions inside the shelter are poor. We used portable photo reflectors to bounce light off the ceiling and back walls. We found 17 elements on six panels. Aside from the "beaver," much of the remaining rock art at this site was difficult to see and to isolate into distinct forms. We made tracings of the zoomorph and some of the other elements. For those elements too faded to see through the acetate, we made sketches instead. One element recorded at this site is a modern graffiti, a big red "S" scratched or rubbed onto the ceiling of the shelter. We believe it is important to document such graffiti so that vandalism and other disturbances can be monitored in the future. The last element recorded at 3CN125 was noticed by a crew member standing outside the shelter and quite some distance away. This element is located on the shelter exterior in a small natural indentation or "cup" on the rock face. It is a small rayed figure, possibly a sunburst or star. The uneven surface prevented us from making a tracing. This was a great example of the value of teamwork when surveying rock art sites. A crew of five worked on this site for about four hours.

The third site, 3CN157, is a long, low overhang with a small alcove at the south end that contains two elements. Work at this site was difficult because the elements are badly faded. The rock is also iron rich and red stains appear naturally on many rock surfaces, making it difficult to distinguish stains from pictographs. Upon careful examination, we decided that at least two faded rock art images are present. One person spent about 45 minutes documenting basic site and element information. We drew a field sketch, but did not make tracings.

Day 3

On the third day we again documented three sites, this time spread over quite a distance. Although located in the same hollow, they could not be mapped from a single instrument station. We began at 3CN127, a shelter that is 25.4 m long, but only 4 m deep and 3 m high. The rock art is concentrated in an area about 2 m long at the eastern end. We examined other rock surfaces and crevices, but found nothing else. We counted ten elements, divided into two panels, at this site. Panel 1 has eight elements and Panel 2 has two small faded elements; Panel 1 was the main focus of our efforts. Panel 1 has two nearly identical images interpreted as "masks," and a third that is very similar but more faded, perhaps because it was created at an earlier time. Other elements in this panel are two very faded handprints and some partially faded images of indistinct form. We were able to trace Panel 1 in its entirety because all of its elements were concentrated on an accessible vertical surface. Two crew members completed this tracing in approximately two hours. The benefits of the technique soon became apparent: two faded handprints that were very difficult to see with the naked eye, and nearly impossible to capture in a photograph, showed up very clearly on the tracing. Although some images remain enigmatic, the tracing allowed us to "collect" the entire panel in a form that permits further studied in the lab.

The two remaining sites, 3CN126 and 3CN128, each contain only one rock art element, so the work proceeded easily and quickly. Most time-consuming was the topographic mapping of these shelters and their surrounding terrain. The two rock art elements were clear but somewhat faded, so we made tracings of each. The element at 3CN128 is a line drawing enclosing a series of dots. An area of rock art at the lower part of the element had broken away from the wall taking with it the edge of the art. Our tracing accurately shows this feature. The element at 3CN126 is a simple outline of a circle with two flattened elliptical protrusions. Measuring and filling out the forms at each of these sites took only an hour or so. Mapping took about two hours at each location.

We also recorded graffiti at 3CN126, including some interesting recent rock art done in a style to imitate Native American art. This was a ten-pointed star resembling a Southwestern motif, freshly drawn onto the shelter ceiling with charcoal. Because of the careful execution, the medium, style, and design of this element, there is a very real possibility it could be mistaken for authentic Indian rock art by future investigators. Full documentation at this time creates a record of its recent origin. (It was known from previous observation that this image must have been made within several weeks of our visit.) Other graffiti was rubbed onto the rock surface in red. Although we could tell it was modern, future visitors to the shelter might not be able to make this determination. This is why we strongly advocate that all modern graffiti at rock art sites be carefully recorded and clearly identified on the site forms and in the computer database. Day 4

On our final day of fieldwork we visited 3CN130. Like 3CN127, this is a long shelter with rock art concentrated in one area. This site contains one of the few known petroglyphs (carved rock art) in Petit Jean State Park, in addition to a considerable number of well-preserved pictographs. All the pictographs are on the shelter ceiling. The petroglyph is on a horizontal shelf in the same area as the pictographs. We counted 14 elements distributed amongst four panels, defined as groupings on distinct rock surfaces. After documenting each element, we recorded additional information for the panels, and made tracings. Tracing a petroglyph is a bit different than tracing a pictograph. Instead of outlining or stippling over areas of pigment, we traced inside the pecked or incised design. Some researchers will trace each individual peck mark, a method requiring a great deal of time and patience but resulting in extraordinary detail. We followed a less demanding approach that still provides a useful and accurate result: we carefully stippled the outline of the pecked area, then added stippling within the outline to indicate the complete area of the petroglyph. One person spent about 45 minutes tracing the petroglyph in this way.

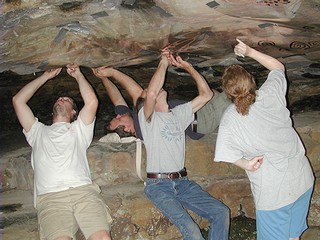

The composition of pictographs on the ceiling at this site is complex. The individual elements include motifs such as swirls, curved lines, dots, and handprints. One element is a long, wavy dotted line stretching more than one meter along the ceiling. The dim light in the shelter and the position of some of the art on the ceiling meant that drawing and photographing the elements in relation to each other was very difficult. Nevertheless, we succeeded in making a tracing of the entire ceiling. This required several contiguous Mylar sheets, which we marked at the edges to show where the sheets conjoined. Tracing this large area — roughly two by three meters — engaged the entire six-person crew for approximately one and one-half hours.

Summary The fieldwork at Petit Jean State Park provided valuable experience in meeting the many challenges of documenting rock art, and gave us ideas for improving the new recording forms. We were able to maintain and refine a basic plan that is now the recommended procedure for recording rock art sites in Arkansas. This plan consists of the following general steps, each one facilitated by the new AAS Rock Art Site Record Supplement (which can be downloaded along with a set of instructions from the Resources section of this Web site):

The organization of the Rock Art Site Record Supplement reflects this basic process and will aid in collecting the appropriate information for each rock art site that is documented in the future. |

| Home | Quick Facts | Interpretations | Articles | Technical Papers | Resources | Database | Just For Kids | Picture Gallery | Buy the Book! |

|

Last Updated: April 23, 2007 at 3:42:41 PM Central Time

|