The Chronological and Cultural By George Sabo III The first people to settle the mid-South were Paleoindians, who descended the Mississippi Valley from the Great Plains about 12,000 years ago. Upon reaching what is now Arkansas, Paleoindians first occupied the Delta region bordering the Mississippi River. Descendants of these immigrants then expanded into other parts of Arkansas, including the Ozark and Ouachita Mountains and the Gulf Coastal Plain. In mountainous western Arkansas, Paleoindians entered habitats where rock art could be created. At the moment, we cannot say whether Paleoindians created any rock art in Arkansas. In many parts of the western United States, rock art depicting Ice Age animals, such as mammoths and mastodons, must be the work of Paleoindians. We have not identified any rock art illustrations of Ice Age animals in Arkansas; all the animal images so far recorded represent modern species.

The waning of Ice Age conditions brought many environmental changes. Forests and prairie grasslands expanded, providing a range of edible plants. The Pleistocene megafauna went extinct, but there was rich hunting of animals such as buffalo, deer, rabbits, squirrels, and turkeys. Rivers and streams, no longer icy cold, filled with fish, shellfish, turtles, beavers, otters, and waterfowl. Archeologists call this time period, from 10,000 to 2,500 years ago, the Archaic Era. The ancient Native Americans who lived during this period, descendents of the Paleoindians, developed diversified hunting and gathering economies. We cannot positively assign any Arkansas rock art to this period, but archeologists who study rock art on the American Great Plains recognize an "early hunting tradition" of images depicting economically important animals and an occasional hunting or trapping scene (e.g., Keyser and Klassen 2001). This Plains rock art tradition began during the Archaic Era, as revealed by radiocarbon dating of rock art pigments. It is reasonable to suggest that some Arkansas rock art animal images might represent a related tradition of similar age.

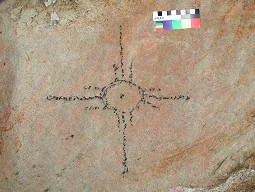

During the latter part of the Archaic Era, beginning around 4,000 years ago, Native Americans began to domesticate some grain-producing plants. Among the cultivated plants were lambs-quarters, knotweed, sumpweed, sunflower, maygrass, and little barley, plus several kinds of squashes. The addition of gardening to the economy and the presence of small village settlements signify the next era of prehistory, called the Woodland Era, and dating from 2,500 to about 1,000 years ago. Some rock art images of economically important plants may date to this era. An important material development of the Woodland Era was the invention of fired clay pottery. People used ceramics for any purposes, including cooking dried grains into porridges and stews. Much Woodland pottery is plain or minimally decorated, but by Middle Woodland times various decorative motifs based on geometric and curvilinear designs were common, especially on vessels used in mortuary ceremonies. Rock art motifs of similar geometric and curvilinear designs might date to this period. The final episode of prehistory in the Southeast is the Mississippian Era. Mississippian Indians performed many ceremonies connected with agricultural cycles and social events. These ceremonies used a variety of material objects decorated with religious symbols, such as the cross-in-circle motif representing the center of the three-layer universe.

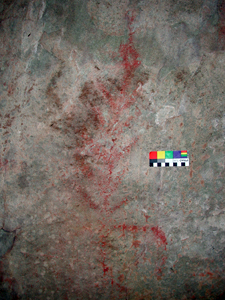

Much Arkansas rock art illustrates similar motifs. For example, the cross-in-circle motif is found at numerous rock art sites and is similar to designs painted on late Mississippian pottery. We have recorded a large body of such correspondences, and can infer a relationship in time and cultural tradition between the makers of the pottery and the makers of the rock art. The arrival of European explorers in the Mississippi Valley, beginning with Hernando de Soto's 1539–43 expedition, brought disease and strife to a region already suffering the effects of intense and protracted droughts. Colonization by France, Spain, and England in the eighteenth century further reshaped the cultural landscape and brought new economic opportunities to surviving American Indian communities. Horses, firearms, and battle with Euro-Americans are frequent subjects of historic era rock art in many parts of the country. In Arkansas, Jerry Hilliard identified one rather poorly-preserved pictograph image that appears to show a horse and rider.

Many Arkansans, from the nineteenth century to the present, have felt compelled to leave their names or initials on exposed rock surfaces, often at or near Native American rock art sites. We call modern examples made with spray paint or marking pens graffiti, and unfortunately these markings often deface earlier rock art. In some cases, purposeful vandalism of ancient rock art clearly was the motive. On the other hand, many nineteenth and early twentieth century personal inscriptions provide an interesting and useful form of documentation about the historic settlement of Arkansas.

People continue to make rock art today. Occasionally we find very recent examples, made perhaps by individuals seeking spiritual fulfillment or simply a way to express their artistic talents. It is important for archeologists to document these examples, so that future researchers do not mistake them for historic Indian or prehistoric rock art.

References Cited Keyser, James D. and Michael A. Klassen |

| Home | Quick Facts | Interpretations | Articles | Technical Papers | Resources | Database | Just For Kids | Picture Gallery | Buy the Book! |

|

Last Updated: April 17, 2007 at 11:01:39 AM Central Time

|