The Narrows Rock Art in Archeological Context by Jerry Hilliard A contract between the Ozark-St. Francis National Forests and the Arkansas Archeological Survey resulted in 1995 Archeology Week excavations at The Narrows, a rock art site in Crawford County, Arkansas. The work was conducted to assess past looting activities and to identify any remaining intact cultural deposits. Areas of undisturbed midden, rich in botanical, faunal, stone tool, and ceramic material, were discovered. One feature, interpreted as a dump of refuse from cleaned-out hearths within the shelter, was identified. It contained a large amount of fire-cracked rock, charred nutshell, and burned bone. Radiocarbon dating indicates the refuse in Feature 1 ranged in age from A.D. 1195-1495 (2 sigma, 95% probability); the most likely date for the episode that created Feature 1 is around A.D. 1435. Our most exciting discovery consisted of pigment-stained stone fragments, abrading tools, and hematite, an assemblage we linked to rock art production at the site. A date for creation of the rock art was established by association with these artifacts. The rock art was produced in the course of fall/winter occupation by a small number of people related in material culture to Arkansas River Valley Spiro and/or Fort Coffee phases. Introduction

The Narrows shelter (3CW35), located just below a ridge crest east of Mountainburg, is locally famous for its unique rock art panels of human figures. The site's location just below a county road has made it a favorite place for visitors over at least the last 60 years (Figure 1) . Unfortunately, a number of these visitors have scratched their names on the walls and haphazardly dug into the archeological deposits, partially destroying an important archeological resource. Despite efforts by the Ozark-St. Francis National Forests to stop these activities, they continue to occur. Investigations conducted in 1995 were planned in response to a looting and vandalism history so severe, it was apparent the scientific record of the shelter interior might soon be lost entirely. These investigations produced the first direct association in Arkansas between rock art and nearby archeological deposits in a primary and datable context. In this paper, we briefly review the history of archeological work at The Narrows and establish a cultural context for the unique rock art at the site. Previous InvestigationsThe Narrows was officially recorded as an archeological site in 1934, when a crew under the University of Arkansas Museum Director, Samuel C. Dellinger, visited the site and made brief notes (University of Arkansas Museum Field Book No. 14, page 50). They found 28 metates, or grinding basins, on the surface, named the site ?Narrows Bluff Shelters,? and remarked on its ?hieroglyphics.? Their visit may have been precipitated by the Civilian Conservation Corps' discovery of the site during construction of State Highway 348, located just above the shelter. The CCC built a native stone stair and walkway to the site for tourism purposes. Local residents have referred to the site for many years as ?Indian Writing Rocks? as well as The Narrows. In August 1955, Clyde Dollar made the first of many visits to the site, culminating in excavations that took place intermittently between November 1, 1957 and April 1958. Dollar's notes, brief report, and excavated artifacts were submitted to the University of Arkansas Museum on April 29, 1958 (University of Arkansas Museum files, 3CW35). His 1957-1958 excavations were halted by overseas service in the army. Dollar wrote a second, similar report dated May 7, 1962, in which he described the site and his excavations and gave recommendations for preservation and further work. Additional investigations of the site were not conducted until the late 1970s, when Gayle Fritz and Robert Ray of the Arkansas Archeological Survey visited a number of rock art sites in the state. The work by Fritz and Ray was the first comprehensive study of Arkansas rock art. Their survey culminated in a thematic nomination of Arkansas rock art sites to the National Register of Historic Places in 1981. They later published their descriptions and interpretations of The Narrows rock art, as well as other sites (Fritz and Ray 1982) Fritz and Ray viewed The Narrows as unique among the rock art sites they inventoried, particularly with respect to the number of anthropomorphs and the fact that most of these occur in one large panel (Figure 2) . Describing this panel, Fritz and Ray wrote:

The largest anthropomorph is 60 cm tall including a headdress with spiked elements (possible feathers?) radiating upward and outward from the top of the head. The right arm holds a long, slightly curving spearlike object which ends in two prongs. The five figures across the top row and nine or 10 figures across the bottom row of the panel range from 25 to 36 cm in height. They were created by pecking with some abrasion, and black pigment was applied to the pecked-out areas. Several have spots of red pigment under the arms and between the legs. The figures in this panel are all stylistically similar although some variation exists with respect to position of the arms. Most hold elbows straight out, upper arms parallel with shoulders, with forearms hanging down vertically. Several, however, have arms forming curves rather than right angles, and the arms on one figure circle around to the hips. Bodies are generally rectangular with a few being more ovoid. Legs flare slightly outward in an inverted V-pattern. Feet, where they can be detected, are turned outward (Fritz and Ray 1982:241-242).

Fritz and Ray also described three other areas of petroglyphs at The Narrows. A smaller group of figures is 65 cm east of the main panel; another single anthropomorph is 3 m east of this second group. West of the main panel are two distinctive anthropomorphs, both with bodies solidly pecked but no pigment added. The lower of these two figures is 30 cm tall and wears what has been interpreted as a headdress depicted by five vertical lines extending from the top of the head (Fritz and Ray 1982:243). Two more distinctive features of this figure are the right hand with four exaggerated spread-out fingers, and the left hand holding a paddle or fan-shaped object (Figure 3) . A number of other very faded anthropomorphs occur under these two figures. Two geometric designs also are seen at The Narrows: an incised cross inside a slightly irregular circle, and a simple incised cross with horizontal bar. Fritz and Ray characterized The Narrows petroglyphs as stylistically similar to Plains rock art. This interpretation is based on the predominance of anthropomorphs arranged into horizontal panels, and the rectangular body form (Fritz and Ray 1982:244). As noted by them, and in more recent studies (Sherrod 1984; Hilliard 1989), influences of both the Plains Tradition and the Eastern Woodland styles appear to be represented in Arkansas. 1995 Investigations

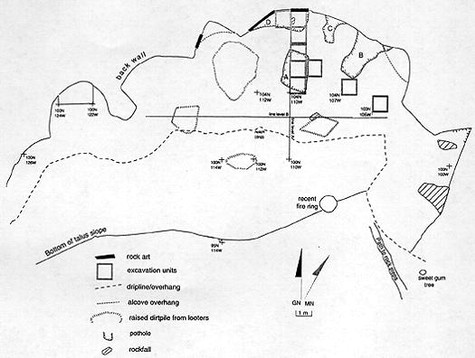

The 1995 excavations were planned for Arkansas Archeology Week (April 3-8), an annual public education event involving many kinds of activities around the state to enhance awareness and support for archeology in Arkansas. A challenge cost-share agreement between the Arkansas Archeological Survey and the Ozark-St. Francis unit of the U.S. Forest Service funded the work. Much of the site plan map and grid unit layout were finished by the end of March. We also made logistical plans for visitor tours, submitted press releases to local newspapers, and printed a flyer for distribution to visitors. School group tours were organized by the Boston Mountain Ranger District. In addition to these scheduled tours, approximately 100 ?drop-in? visitors viewed the site during Archeology Week. The placement of excavation units was based on our judgmental assessment in order to retrieve the most information in a very limited time period. To achieve this goal, we cleaned out a looter's pothole in the approximate center of the shelter, establishing a straight wall that provided a convenient stratigraphic profile to guide the work in other excavation units. This pothole had been mapped by the Forest Service in a previous assessment of looting (Pfeiffer 1994); it apparently was dug sometime between 1992 and late March 1994. A 1 meter wide trench was laid out perpendicular to the back wall of the shelter, intersecting the looter hole near the front of the shelter (designated A on the map below). Use of trench excavations in rockshelters is one of the most effective ways to gain meaningful information of site stratigraphy and feature content (Straus 1990:287). Additional excavation units were planned for an area east of the trench, and to its west in a natural alcove. These units were placed to examine different areas of the shelter interior and to determine the extent of damage from looting. The unit in the alcove was believed to be in one of Dollar's 1957/1958 excavation areas.

Soil matrix was troweled or shoveled, depending on the nature of strata encountered. A soil profile was initially established based on the units that comprised much of ?pothole A.? Excavation proceeded by following these soil strata as determined from the pothole profile. In every 1 x 1 meter excavation unit, a sample of soil matrix was collected from each 5 cm level within a stratum. These samples were bagged and transported to Fayetteville for flotation, a process that uses water pressure to separate and recover tiny artifacts, charcoal, seeds, and minute bone or shell fragments. During the excavation, we discovered that a portion of the trench matrix had been previously looted. Fortunately, the color and texture of these disturbed soils were easily discerned, and we did not waste time by continuing to process this soil in the same manner as intact deposits.

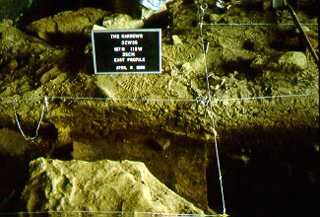

In all, seven contiguous 1 x 1 meter units were excavated in a line perpendicular to the back wall of the shelter. The undisturbed north portion of 104N 110W in the area of ?pothole A? had indicated an intact midden deposit was present. This midden, designated Stratum 3, was buried by about 35 cm of light brown sand and sandy silt loam. These upper layers (Strata 1, 2, and 2a) had been disturbed by previous digging and recent infilling caused by erosional wash. Stratum 3, the midden layer, is a very dark brown to black silt loam, easily distinguished from the disturbed soils overlying it. Soil from the unit located in the alcove (103N 124W) was initially sifted using ¼-inch mesh screen. Sand and recent historic artifacts were encountered, and we soon realized that the whole alcove had been previously excavated. This alcove is probably the area where Dollar (1962:3) recorded a soil depth of only 2 1/2 to 3 feet; we recorded a similar depth in our unit. Due to the pervasive disturbance, work in that area was halted. Other areas sampled indicate that the western portion of the shelter is heavily disturbed; this is likely the area Clyde Dollar excavated in 1957. Another area that has been severely looted is along the back wall, where our excavation units 108N 110W and 108N 111W contained recent mixed sediments and modern trash. These units also were extremely damp, with water seeping though a crack in the back shelter wall. This seep is the result of rainwater percolating down through the sandstone bedrock. The eastern portion of the shelter contains undisturbed intact deposits like those discovered along the 110W trench. Portions of the Stratum 3 midden in units 104N 110W and 105N 109W were left unexcavated so they may be preserved for the future. Site ContentThe Stratum 3 midden in our trench confirmed that looting had not totally destroyed prehistoric deposits at the site. Pockets of intact midden and portions of features remain within the eastern half of the shelter interior. As mentioned above, the upper strata (1 and 2) consist of sandy loam soils that were washed into the shelter from surrounding areas. These strata contain mixed historic and prehistoric artifacts, including objects left behind by modern human activities such as looting and camping. Weathered sandstone from the walls and ceiling of the shelter comprises a small percentage of Strata 1 and 2 sediments. Stratum 2a is an irregular deposit characterized by mixing of the intact midden (Stratum 3) with the redeposited soils (Strata 1 and 2). This mixing is due solely to looting. Stratum 2a was only noted in unit 106N 110W.

Looting in the trench area appears to have focused on digging out the rich Stratum 3 midden deposit. We discovered areas where the midden had been completely destroyed (e.g., in unit 107N 110W) right next to blocks that were untouched (e.g., in unit 106N 110W). In unit 105N 109W, adjacent to the north-south trench, upper portions of the midden had been looted and later backfilled, creating a zebra-striped profile (Figure 5) . We collected flotation samples from the intact lower levels of the midden. Midden depth, where undisturbed, began at about 35 cm below ground surface and extended to the bedrock floor of the shelter, up to 85 cm below present ground surface. Sandstone fragments, many of them cracked or shattered by fire, were abundant in the midden, especially in unit 106N 110W. Two large, flat sandstone slabs found in units 104N 110W and 105N 110W within the midden appear to have been used as anvils or other flat work surfaces. The Stratum 3 midden is composed of refuse that apparently was deposited over a relatively short period of time. Artifacts discovered in the midden suggest various specific work-related activities, such as nut processing, pigment processing, stone tool manufacture, and rock art production. Debris may have ended up in this central portion of the shelter interior because it is damp and unsuitable for habitation, thus offering a convenient place to deposit trash from adjacent living areas. We think that any earlier debris was probably cleaned out of the shelter prior to the deposition of Stratum 3. This would have provided sufficient space to create the petroglyph panels. Shelter bedrock (Stratum 4) is about 1.5 meters below the petroglyphs at the back wall, a convenient working height from floor to panel. During and after production of the rock art, discarded tools and hearth debris accumulated below the panels, eventually raising the floor to the level of the petroglyphs. The artifacts associated with rock art production found in Stratum 3 provide support for this interpretation. One feature (Feature 1) was identified based on analysis of material from unit 106N 110W in the Stratum 3 midden. The quantity of fire-cracked rock, charred nutshell, and burned faunal fragments in this unit, as compared to other units within the stratum, warrants the feature designation. This material appears to be a dump of refuse cleaned out of a hearth or hearths by prehistoric occupants of the shelter. It is unlikely to represent an intact hearth or series of hearths, as no ash lens or burned soil was present. The matrix is dark in color and rich in organic content, indicating the presence of food refuse. The surface of Feature 1 originated within the Stratum 3 midden, and fill extended to the bottom of this stratum, or to the shelter bedrock floor. Unfortunately, the horizontal dimensions of Feature 1 could not be determined due to severe disturbance of the soil matrix in adjacent units. Much of this disturbance is the result of past looting, observed in wall profiles in the form of shovel-dug pits, and in fill content by the presence of modern refuse. Stratum 3 midden deposits in units 105N 109W and 104N 110W are similar to Feature 1 in four ways: 1) the top surface is at about the same elevation; 2) color and texture of midden matrix are identical; 3) the kinds of artifacts present are similar; and 4) ceramics are similar in type and age. Feature 1 is therefore interpreted as a discrete ?episode? of Stratum 3 midden development. It is clear that Feature 1 represents a dump of debris onto the bedrock floor of this portion of the shelter. Possibly, the rest of the Stratum 3 midden deposits are part of the refuse dump identified as Feature 1, but this could not be determined due to the intrusive looters' pits. In any case, it appears the shelter floor was clean just before the refuse was dumped. Radiocarbon dating provides additional data about the nature and context of Feature 1. Hickory shell samples from three 5-cm levels of Feature 1 were submitted for dating. Intercept data of two samples (Beta-95069 and Beta-95071), taken from 45-50 cm and 80-85 cm respectively, are very close in age (cal A.D. 1410 and cal A.D. 1435). The A.D. 1435 date is from a sample taken at the bottom of Feature 1, just above the sandstone floor. A somewhat dissimilar date (cal A.D. 1270) resulted from intercept data obtained from a third sample (Beta-95070), taken at 65-70 cm in depth. The three radiocarbon assays indicate a time frame of A.D. 1195-1495 (2 sigma, 95% probability) for the materials that were used and subsequently deposited in Feature 1. The two fifteenth century dates, which include the sample taken from the bottom of the feature, indicate the refuse was dumped here no later than A.D. 1495, and probably no earlier than about A.D. 1400. The A.D. 1270 intercept date is explained by the interpreted function of Feature 1 as a refuse dump from cleaned-out hearths within the shelter. It would not be unusual for some earlier material to get mixed in with the hearth debris during such activities. The two similar dates, and especially the intercept data (cal A.D. 1435) for the sample at the bottom of Feature 1, are viewed as good evidence of the approximate age of actual refuse disposal. Pieces of fire-cracked sandstone are predominant in Feature 1. These rocks were likely used in and around adjacent fireplaces and thrown into the Feature 1 fill as the hearths were cleaned. Heated sandstone also may have been used in processing nut resources; an abundance of charred hulls along with discarded sandstone was found in the midden. The charred nutshells in Feature 1 probably were gathered up after the nuts had been processed into food, perhaps as hickory milk, and then used as fuel in the hearths.

Aside from fire-cracked rock and charred nutshells, small burned bits of bone were also abundant in the Feature 1 fill. Turtle and other animal bones seem to have been intentionally smashed, perhaps to render them into grease and oil, just as nuts were processed into an oily substance known as hickory milk. Rendering of bone into grease has been documented for Native American Plains groups, and on archeological sites with similar faunal and fire-cracked rock assemblages (Hughes 1991). It may have been a widespread practice for obtaining high-fat foods. Fat content of the diet would have been of particular importance during cold weather months, a time of likely occupation at The Narrows (since nuts are available late in the fall). In addition to the evidence of food refuse, ground-stone abrading tools made from fire-cracked rock, chipped stone material, pigmented stone fragments, and hematite were also found within Feature 1. These artifacts indicate special-use activities. Rock art production is interpreted from the presence of abrading stones and tabular pieces of red-painted sandstone. The abrading stones were expedient tools probably used to smooth the walls of the shelter before the application of rock art figures. These tools were selected from among the fire-cracked rocks in the hearth refuse. After use they were simply tossed into the refuse heap that became Feature 1. The rocks with paint on them are interpreted as wall art fragments that were cleaned off the shelter walls prior to the creation of new images. These art fragments were discarded along with the sanding blocks. Hematite found in Feature 1 may have been used to apply pigment directly to rock art figures. Alternatively, hematite fragments may have been discarded from hearth areas where they were being heated for processing into paint. In any case, the presence of pigment-stained stones, hematite, and abrading stones form an assemblage of related artifacts necessary for the production of rock art. The presence of these artifacts in the Feature 1 fill suggests that rock art related activities were going on around the same time the refuse was dumped, about AD 1435.

The Narrows in Regional Context The lack of specific context for rock art is a major problem in the study of these sites. Until recently, many archeologists in eastern North America saw rock art as interesting, but esoteric, and generally offering little to advance our understanding of the past in a concrete way. There have been a few exceptional studies of rock art in the Southeast, such as at Mud Glyph Cave (Faulkner 1986) and a recent regional study in Missouri (Diaz-Granados 1993). Fortunately, archeologists are beginning to develop new perspectives—for example, the idea of cultural landscapes—in which rock art can play a more significant role (Hilliard 1993). Our investigations at The Narrows addressed certain questions about the archeological context of the rock art panels. Are there materials in the cultural deposits at the site associated with the production of rock art motifs? Is it possible to determine a temporal association between rock art production and excavated cultural deposits? Does archeological evidence suggest ritual behavior associated with the rock art? The 1995 excavations indicate the site was occupied primarily during fall and winter months in the late prehistoric period. Radiocarbon dates provide a temporal context around A.D. 1435 for the feature in which a tool assemblage for rock art production was identified. What links can be established to regional cultural manifestations of that time period? We believe that Arkansas River Valley peoples were the likely inhabitants of The Narrows shelter. They may have belonged to cultural groups that archeologists know as the Spiro or Fort Coffee phases. Artifacts, particularly Poteau Plain pottery and the predominance of siltstone implements, strongly suggest a connection to these Arkansas River peoples, rather than to the historic Osage, or to peoples affiliated with the Neosho phase, which is characterized by distinctive Neosho Punctate pottery. Siltstone tools, especially hoes, were produced at The Narrows from a local source of raw material. These hoes were likely used elsewhere, perhaps to the south along the Mulberry and Arkansas river drainages, areas where shelter inhabitants likely had their spring and summer living sites. There, the hoes would be used to break ground for planting. Surplus hoes could be traded. Unfortunately, only limited studies of the manufacture and use of these tools have been conducted. Existing survey and other data suggest that The Narrows is unusual for the region in having siltstone as the predominant raw material used for production of chipped stone tools. It is also interesting that hoes, normally associated with spring and summer agricultural use, were being made during the fall and winter seasons. SummaryDuring The Narrows occupation, nut resources were harvested and processed, and local game was procured, butchered, and consumed at the site. Analysis of artifacts from Stratum 3 provided evidence for the designation of Feature 1 in unit 106N 110W. The Stratum 3 matrix in this unit contained large quantities of fire-cracked rock, charred nutshell, and fragments of burned bone. Feature 1, within the midden stratum, was a refuse pile deposited directly on the shelter bedrock floor. Fill of Feature 1 is interpreted as primarily food, fuel, and tool-making debris cleaned out of hearths elsewhere in the shelter. Analysis of the Feature 1 fill further suggests production of rock art took place at the time of refuse disposal, or about A.D. 1435. Hematite, pigment-stained sandstone fragments, and abrading tools constitute the assemblage that points to rock art related activities.

Makers of The Narrows petroglyphs carefully planned their location within the shelter, probably going so far as to clean out the soil and cultural debris all the way down to shelter bedrock at the back wall/floor juncture. Pieces of conveniently available fire-cracked sandstone were roughly shaped to appropriate size and used as sanding blocks to smooth the wall in the area of the proposed art panel. Waste from this activity, including some fragments of older rock art, were tossed into the Feature 1 refuse dump along with broken and expended tools. We don't know what The Narrows petroglyphs mean. The panel of linked anthropomorphs may represent creation or culture hero myths. It may depict aspects of social organization, genealogy, or a significant local event. It may represent a ritual or celebratory dance. The shelter may have functioned as a place for recreating myths through storytelling, ritual, and art. Stylistic traits of the petroglyphs suggest a late prehistoric date, which correlates nicely with the radiocarbon dates obtained from the 1995 excavations. It is not surprising that motifs stylistically similar to Plains rock art should occur at this late date in western Arkansas. Plains influence, established and maintained by extensive travel and trade networks in this and adjacent regions, was strong among Caddoan speaking peoples. Rock art at The Narrows, and the related archeological deposits, are viewed here as material remains of an indigenous people of the southern Ozarks and Arkansas River Valley. AcknowledgmentsGary Knudsen, Ozark-St. Francis National Forests Archeologist, gave support and encouragement in the planning stages and during the course of the excavation. Rita Pruitt of the Boston Mountain Ranger District served as the contact person for scheduling tour groups. Mike Dryden, Boston Mountain Ranger District Archeologist, helped direct excavations and assisted in public relations.

A number of Arkansas Archeological Society members as well as UAF Anthropology graduate students assisted in the excavations. Russell Scheibel and Louis Harvey, a Bradford University, U.K. student working with the Survey, assisted Hilliard and Dryden for the duration of the excavation. Robin Toole, archeologist with the Forest Service, was assigned to fill in for Dryden on Friday when he had another work commitment. Volunteers included Survey archeologist Randy Guendling, and Society members Linda Jones, Sam Baker, Glen Akridge, Rita Carroll, Joan Pottinger, and Nese Nemec. University of Arkansas Anthropology graduate students Judy and Eben Cooper, Angela Tine, Melissa Memory, Sarah Moore, Courtney Waugh, and Tom Gannon also helped. Larry and Virginia Swaim of the Northwest Arkansas Archeological Society, Joanna Wilson, and Norma Hoffrichter helped wash and sort all dry screen samples. This work was conducted on two Monday evening lab sessions directed by Dr. George Sabo III. Dr. Michael P. Hoffman, Curator of Anthropology, University of Arkansas Museum, authorized access to the Museum's 1957/1958 collection from Clyde Dollar's excavation. Dr. Charles R. McGimsey III, Emeritus Professor, Arkansas Archeological Survey, provided background information on Dollar's work in Arkansas during the late 1950s. Aside from his work in the field, Randy Guendling of the Arkansas Archeological Survey acted as a sounding board for Hilliard's various interpretations of site content and stratigraphy. Dr. Gayle J. Fritz, Washington University-St. Louis, conducted the botanical analysis and provided insights from her previous rock art research in Arkansas. Eben Cooper of the Center for Advanced Spatial Technologies, University of Arkansas, contributed his expertise on the use of photogrammetry to document rock art at The Narrows. Although his research began long after the 1995 Archeology Week project, preliminary results show great promise for this technique. Janie Kellet printed all field and artifact photos. Mary Lynn Kennedy produced the site map figures. Finally, we thank Lela Donat, Archeological Survey Registrar, for assisting in producing some of the figures for the report. References CitedDiaz-Granados Duncan, Carol Dollar, Clyde D. Faulkner, Charles H. Fritz, Gayle J. and Robert Ray Hilliard, Jerry E. 1993 Arkansas Rock Art Landscape. Field Notes, Newsletter of the Arkansas Archeological Society 255:3-5. Hilliard, Jerry E., Michael Dryden, Gayle J. Fritz, and Eben S. Cooper Hughes, Susan S. Pfeiffer, Michael A. Sherrod, P. Clay Straus, Lawrence Guy |

| Home | Quick Facts | Interpretations | Articles | Technical Papers | Resources | Database | Just For Kids | Picture Gallery | Buy the Book! |

|

Last Updated: April 12, 2007 at 2:52:38 PM Central Time

|

Fifteen or 16 of the figures (a few are indistinct) are arranged in a panel consisting of two rows, one on top of the other, with a much larger figure on the west end which covers the height of both rows. The feet of the lower row of figures are near the present ground level. This panel extends approximately 2 m horizontally and 75 cm vertically.

Fifteen or 16 of the figures (a few are indistinct) are arranged in a panel consisting of two rows, one on top of the other, with a much larger figure on the west end which covers the height of both rows. The feet of the lower row of figures are near the present ground level. This panel extends approximately 2 m horizontally and 75 cm vertically.