|

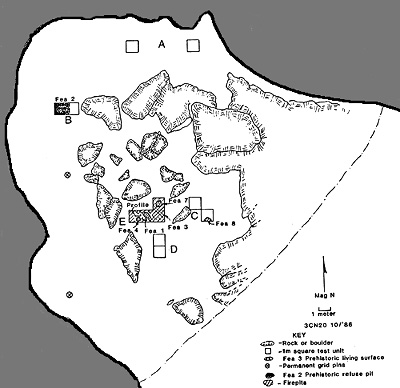

Gimme Shelter: Test Excavations at Rockhouse Cave (3CN20) in Petit Jean State Park By We witness one of the more valuable aspects of the association between the Arkansas Archeological Society and the Arkansas Archeological Survey when a cooperative effort produces significant new information about archeological resources in our state. Such was the case one recent weekend last October [1986], when several Society members joined Survey archeologists Jerry Hilliard, John Riggs, Norma Hoffrichter, and George Sabo III for test excavations in Rockhouse Cave (3CN20), an important archeological site located along the northern edge of the Ouachita Mountains in Petit Jean State Park. Society members volunteering their time and considerable expertise to this effort included Scott and Glenn Akridge, Rosemary Bergeron, Lynn Boise, Linda Driggers, Mary Ann Goodman, Danny Moore, Clara Penney, Bill Shumaker, and Dennis Smith. Rockhouse Cave is the big, picturesque shelter known to anyone who has visited Petit Jean Mountain and the State Park. It can be seen from the road and is one of the major attractions on the hiking trails. It also has on its walls and ceilings a considerable amount of prehistoric rock art, very badly covered with modern spray paint graffiti. Clay Sherrod, in his study and inventory of rock art on Petit Jean Mountain, recorded as many of the prehistoric figures as possible and alerted the Park personnel to the needs for preservation. State Park officials are concerned both with being able to tell visitors about this most unique cultural resource in the Park and with the problems of preserving it. After research on rock art and its preservation in other parts of the country and consultation with the State Archeologist, Hester Davis, the Park decided to embark on an effort to remove the modern graffiti. To do that, however, requires the use of chemicals, and Hester indicated that before these materials were allowed to seep into the deposits on the floor of the shelter, test excavations should be done in order to give some idea of how much damage had been done over the years to the prehistoric deposits by thousands of visitors. Ben Swadley, the Park ranger most concerned with the problem, was more than helpful to all the volunteers, and the Park supplied lunch (actually carrying it down the trail, too) on Saturday. We thank Ben, Chris Snodgrass, the Park Superintendent, and the other Park personnel for their help and interest. The purpose of the test excavations in Rockhouse Cave was to determine what kinds of archeological deposits existed beneath the floor of the shelter, what condition (disturbed or intact) these deposits were in, and what kinds of material remains these deposits contained. This information was required by Petit Jean State Park in order to plan effectively for the preservation of the site. Consequently, a cooperative program involving members of the Survey, the Society, and Petit Jean State Park was implemented. With limited time in which to make these determinations, a strategy was chosen in which several 1 m square test units were laid out in various parts of the shelter where sufficient floor space for occupation existed in between concentrations of huge, immovable rocks. These test units were excavated stratigraphically, following as closely as possible the natural and/or cultural layers of sediments as they were encountered. Arbitrary 10 cm levels were excavated within natural or cultural layers exceeding this thickness. With the exception of specially designated archeological features, all excavated sediments were dry sifted through quarter-inch (0.64 cm) mesh screens. All materials trapped in the sifting screens, including natural gravels, were bagged for laboratory processing. Also bagged for future water flotation processing were sediments from selected archeological features exposed in the excavations. We hoped these procedures would help insure thorough and systematic retrieval of significant cultural and ecological materials. Description of the excavations and a preliminary assessment of our findings can be most easily summarized by individual floor space areas tested within the shelter. These areas are indicated by the letters A - E on Figure 1.

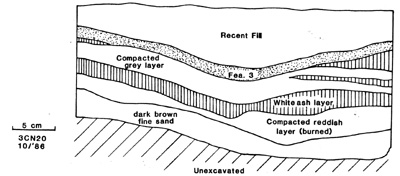

Area A Two test units were excavated in this area along the rear wall of the shelter behind a concentration of very large boulders. The floor of the shelter in this area was relatively flat, and the shelter walls above this area were well covered with modern spray-paint graffiti. In both test units the thin (1 cm) surface layer of gray-colored, fine sandy sediments quickly graded into a yellowish, coarser sand that contained mostly recent artifacts (primarily fragments of glass from broken beverage bottles), a few bits of wood charcoal and charred nut hulls, and even fewer flakes of chert. One of the units also produced a piece of galena and a fragment of lead slag. Galena mines and lead works existed in the area during the Civil War era, according to park ranger Ben Swadley. At depths just below 20 cm in both units, the coarse yellowish sand graded into a layer of decomposing sandstone devoid of any artifacts. Excavations were terminated in these units when it became clear that no intact cultural deposits, prehistoric or historic, existed in this area of the shelter. Area B Excavation of a single test unit was begun in this area by Dennis Smith, who recognized the outline of a pit (Feature 2) extending into the eastern end of the unit just below the thin gray surface layer. This feature was indicated by loose, gray-colored fill surrounded by an arc of rocks that appeared intrusive into the coarse yellowish-orange sediment exposed throughout the rest of this unit. Excavation of the feature area confirmed that it was indeed a pit, so an adjacent unit was opened up to the east. The feature extended completely throughout this unit, so that portions of the pit remain unexcavated. The pit fill extended to a depth of roughly 0.5 m below the surface, and consisted of a loose, fine sandy matrix with occasional rocks. This fill contained burned rock fragments, fragments of burned and unburned animal bone, wood charcoal, burned nut hulls, fragments of mollusk and snail shell, chert flakes, a pitted stone, and chipped stone artifacts. Among the latter category of artifacts were a Williams point, a Big Sandy or White River Archaic point, and a Hardin Barbed-like point. These point types represent the Early to Middle Archaic periods. No historic artifacts were found in the pit fill. A sample of the pit fill was collected for flotation processing in the lab. Area C Two test units were excavated into this sloping floor area between concentrations of large rocks in the front of the shelter. Loose, sandy sediments extended from the surface to a buried layer of densely packed rocks encountered at 20-25 cm below the surface. We did not attempt to penetrate this rock layer. One firepit containing recent artifacts (Feature 8) was identified. The sediments above the rock layer contained a mixture of prehistoric and recent artifacts. The prehistoric artifacts included chert flakes and chipped stone tool fragments, a pitted stone, and several smooth-surfaced, shell-tempered pottery sherds. Two of the sherds were rim fragments exhibiting squared rim edges decorated with short, closely-spaced incised lines. Mary Ann Goodman and Clara Penney also found a tiny bone awl in one of these units. Burned and unburned animal bone, mollusc shell, charcoal, and burned and unburned nut hulls were also found. Area D Two additional test units were excavated in this area adjacent to Area C, also in the open front portion of the shelter. These units revealed stratification almost identical to that found in Area C, and produced a similar assemblage of artifacts and other materials. A mixed sandy layer was encountered beneath a thin (1 cm) surface layer of very fine, gray-colored sand. The sandy layer extended to a layer of rocks encountered at a depth of approximately 15 cm below the surface. Artifacts found in the sandy layer include various bits and pieces of recently-made plastic, glass, and metal items, plus chert flakes and chipped stone tool fragments, pitted stones, and smooth surfaced, shell-tempered potsherds. Charcoal, wood, nut hulls, bone, and shell were also collected. Area E This area encircled by large rocks and boulders in the center of the shelter, turned out to be the location of our most exciting finds of the weekend. Excavation in a single unit was begun by Scott and Glenn Akridge and Danny Moore, and at first the deposits in this part of the shelter appeared to be similar to deposits encountered in adjacent areas C and D. However, at a depth of about 16 cm, a distinctive compacted surface was discovered. This surface (Feature 3) extended out from a rock-filled pit or hearth (Feature 1). As Feature 3 was exposed across the unit, several artifacts were found lying flat upon it, including one shell-tempered potsherd, one Langtry point, and one pitted stone. Impressions were left in the compacted surface when these artifacts were collected. The compacted nature of this surface, the flat-lying artifacts, and the artifact impressions ion the surface, all suggested that Feature 3 was probably a living floor, most likely occupied during the Mississippi period. Adjacent units were opened up to the north and to the east, and Feature 3 continued to extend through these units. One other pit (Feature 7) was encountered in the unit opened up to the north. In the westernmost test unit of area E, a modern firepit was encountered intrusive into the Feature 3 surface. This firepit contained exclusively modern trash including tin foil and a yellow plastic fork. We excavated this pit (Feature 4), and found that it extended down through several other distinctive layers below the Feature 3 surface. An east-to-west profile about 0.5 m in length was cut just to the north of Feature 4 in order to more fully expose the stratified layers extending beneath Feature 3. A drawing of this profile is rendered in Figure 2. This illustration shows two additional compacted layers (possible living surfaces) interspersed by layers of ash. The lowest compacted layer, lying on top of a looser, fine sandy sediment, appeared to be intensively burned and may therefore yield datable archeomagnetic samples. By the time our excavations reached this point early Sunday afternoon, the temperature had dropped to an uncomfortable level in the shelter, and the light was so dim that the profile cut in area E had to be drawn by the light of a lantern and two flashlights (furnished by the Society members, who always come to excavations much better equipped than do Survey personnel). So, after additional flotation samples were collected from area E, the excavations were terminated and all units were lined with plastic garbage bags and carefully backfilled.

As a result of this brief testing program, we obtained quite a bit of significant information about the archeological potential of Rockhouse Cave. Despite the presence of numerous disturbances to the deposits beneath the shelter floor (most of which are from modern campfires), several intact archeological features remain preserved including prehistoric hearths and pits, and at least one intact living surface. Artifacts in direct association indicate that one of the pits (Feature 2) dates to the Early to Middle Archaic period, while the living surface (Feature 3) dates to the Mississippi period. The basal portion of a collaterally-flaked, lanceolate point and two Dalton point fragments (all found in other, disturbed contexts) also suggest that the shelter may contain even earlier deposits. Both Feature 2 and Feature 3 were encountered quite near the modern surface of the shelter, in contexts that could be easily disturbed by modern visitors to the shelter. We did not attempt to ascertain if deeply buried archeological deposits exist below the dense layer of rocks encountered in areas C and D, but this is certainly a possibility that should be investigated. Feature 3 continued to extend beyond the limits of our excavation in area E, and the profile cut also indicated that additional stratified surfaces might also be revealed by further excavation. The lowest surface exposed in the profile cut might yield datable archeomagnetic samples, and charcoal found in association with some of the prehistoric features might also furnish radiocarbon dates. Faunal and floral remains also preserved in these deposits could yield important information about paleoenvironments in the area. These characteristics of the archeological deposits identified in Rockhouse Cave indicate that all reasonable measures should be taken to protect the site from further disturbance, until such time as further archeological research can be undertaken. Reprinted from Field Notes: Newsletter of the Arkansas Archeological Society, Number 214 (January/February 1987), pp. 8-12. |