|

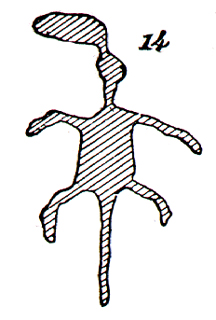

History of Rock Art Research in Arkansas By George Sabo III and Jerry Hilliard "Curious characters cut into the rock" The first published account of Arkansas rock art appeared in the late nineteenth century, when public museums and other institutions relied on private citizens as well as professional scholars to report all manner of scientific facts and discoveries. Edward Green of Clarksville submitted a short note to the Smithsonian Institution's Annual Report for 1881, in which he illustrated and described sixteen petroglyphs from a site in Johnson County (Green 1883). Most of Green's examples were geometric forms, but he also described "reptiles" and sunburst figures. Here is a typical example:

Since his was the first published report, Green was of course unable to compare his finds with any others. More interesting from a historical perspective are Green's "superstitious" and "warlike" interpretations of American Indians—typical nineteenth century stereotypes—as revealed in his description of the site:

Thus was created our first impression of Arkansas rock art: "curious characters … cut into the rock … by some blunt instrument in the hands of an unskillful sculptor" (Green 1883:539).

That was the situation until 1922, when M. R. Harrington of the Museum of the American Indian-Heye Foundation investigated a number of rock shelters in northwest Arkansas. An archeologist by profession, Harrington wanted to document the archeological context and to identify, as far as possible, the makers of the well-preserved wood, bone, shell, and plant fiber artifacts found in the dry sediments of many Ozark sites. His report included this sketch of a pictograph at the Allred Shelter, located along present-day Beaver Lake. According to Harrington's account,

Harrington assigned most of the material he found to a so-called "Ozark Bluff-dweller culture" (a term that modern archeologists no longer use), but he did not speculate on the identity of the artist(s) responsible for the Allred figure.

Nearly a decade after Harrington, Winslow M. Walker also chose northwest Arkansas to carry out investigations on behalf of the Smithsonian Institution's Bureau of American Ethnology. Walker, like Harrington, was a professional archeologist attracted to the area because the "cave region of the Ozarks in northwest Arkansas has long been considered a likely place in which to look for evidence of an early type of American aborigine" (Walker 1932:159). At the time, still decades away from the development of radiocarbon dating techniques, cave dwellers were considered more "primitive" and therefore more remote in time than farmers occupying fertile river valleys, or builders of large earthen or stone mounds or other forms of monumental architecture (another stereotype that even some modern archeologists have been unable to discard). Walker visited three sites where he found rock art. At Jacobs Rock in Searcy County, he saw pictographs "of both animate and inanimate objects—humans, snakes, tracks, sun, moon, stars, and unrecognizable forms" (Walker 1932:164), but did not illustrate them in his report. Unlike Harrington, Walker was willing to draw a connection between the rock art decorating the shelter walls and the archeological contents of the sites he excavated. That the pictographs were made by Indians "seems plausible from the pile of ashes and refuse under the shelter, in which potsherds, flints, and bone fragments were found" (Walker 1932:168). At "Indian Grotto," Walker observed even more petroglyhs:

Walker's study was the first to compare rock art at different sites. What he found most surprising was that "although they are within a hundred miles of one another no two of them exhibit the same type of figures, some being geometric, others naturalistic, and others conventionalized realistic types." From this he reasoned that each type of motif was the work of "a different tribe, perhaps for a different purpose" (Walker 1932:168). Walker and his contemporaries had no way to determine the ages of the archeological deposits they excavated, and were only beginning to understand regional variations in material culture. Nevertheless, they were not fooled by the unrestrained speculations of the ever-hopeful and never-to-be-denied local seekers of "lost Spanish treasure," as the following quotation—referring to the human and horse motifs—demonstrates:

Mid-Century Interests in Petit Jean Mountain

During the mid-twentieth century T. W. Hardison, a physician and amateur archeologist, took a keen interest in the rock art on Petit Jean Mountain near Morrilton. Hardison published a brief discussion (Hardison 1955), and invited another rock art devotee, Raymond Torrey of New York, to examine the Petit Jean sites. After several visits Torrey wrote to Dr. Clark Wissler of the Smithsonian Institution's American Museum of Natural History, seeking advice on the significance of the images. He wanted to promote the development of a state park in the area. According to Hardison, Wissler saw in the Petit Jean sunburst motifs a connection to the Yucatan Mayans, who worshipped the sun. Wissler's correspondence has not been preserved, so it is hard to determine what his conclusions really were, but the Mayan connection is unnecessary, since many Southeastern tribes celebrated relationships with deities represented by the sun. Modern Assessments

The modern era of rock art research began in 1978 when Gayle Fritz and Robert Ray, both of the Arkansas Archeological Survey, started to revisit sites listed in the state archeological site files. Landowners and other local informants provided leads resulting in new discoveries. Fritz and Ray eventually compiled information on 46 sites with rock art and noticed a concentration along the southern border of the Ozark Highlands and the adjacent Arkansas River Valley (Fritz and Ray 1982). Fritz and Ray attempted the first systematic stylistic assessment of Arkansas rock art, identifying connections with Eastern Woodlands as well as Plains styles, and defining the unique Petit Jean Painted style. They were also the first to marshal evidence in support of chronological questions. By identifying similarities between rock art motifs and decorations on pottery and engraved shell artifacts, Fritz and Ray suggested a Mississippian to proto-historic time frame for much of the rock art they recorded. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, Fritz and Ray succeeded in getting 28 of the sites listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It was the country's first thematic nomination for rock art.

Stimulated by the results of the Fritz and Ray study, P. Clay Sherrod of the Office of Research in Science and Technology at the University of Arkansas campus at Little Rock sought and documented additional rock art examples at numerous sites on Petit Jean Mountain and several other central Arkansas River Valley locations. Sherrod published a comprehensive illustrated catalog of several hundred pictographs and petroglyphs. Jerry Hilliard and John Riggs, then of the Arkansas Archeological Survey Registrar's Office (where the state's archeological site files are maintained) also followed up on Fritz and Ray's study by revisiting poorly documented sites on Petit Jean Mountain and other Ozark rock art sites to improve the quality of available information (Hilliard and Riggs 1985, Hilliard 1989). Ben Swadley, of the Arkansas Department of Parks and Tourism, in 1986 initiated a conservation program to document, clean, and protect rock art at Petit Jean State Park, much of which suffers extensive and ongoing damage from graffiti and other vandalism. Arkansas State Parks subsequently applied more than $50,000 in grant monies to develop conservation strategies and implement a conservation program to remove graffiti and protect rock art sites in Petit Jean State Park. In connection with that effort, Arkansas Archeological Survey archeologists worked with volunteers from the Arkansas Archeological Society to conduct test excavations at Rockhouse Cave, which contains some of the park's most spectacular rock art (Sabo 1987). More recently, Survey personnel successfully experimented with the use of near-surface remote sensing techniques, including electromagnetic conductivity, magnetic susceptibility, and electrical resistance, to detect additional buried cultural deposits at the site (Lockhart and Sabo 2001).

More recently, the Arkansas Arhceological Survey received grants from the Arkansas Humanities Council (1999-2000) and the National Endowment for the Humanities (2003-2006) to conduct extensive research at Arkansas rock art sites. This new research, detailed throughout this website, examines rock art images within the larger comparative frameworks of Southeastern Indian art, ritual, and cultural landscapes. Summary and Conclusions From the first impressions recorded in the nineteenth century to the most recent investigations, the studies mentioned here all contribute useful information. The fact that earlier researchers entertained outmoded perspectives on the past does not detract from the importance of their descriptive information. References Cited Fritz, Gayle J. and Robert Ray Green, Edward Hardison, T. W. Harrington, Mark R. Hilliard, Jerry and John Riggs Lockhart, Jami J. and George Sabo III Sabo, George III Sherrod, P. Clay Walker, Winslow M. Copyright ©2001 Arkansas Archeological Survey |