|

What is rock art and what can it tell us about the past? By George Sabo III and Deborah Sabo What is rock art?

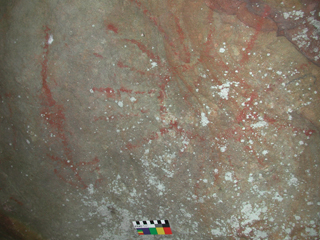

The term "rock art" refers to images rendered on immovable natural rock surfaces, such as bluff faces, cave walls, and large boulders. Painted images are called pictographs. Pecked, carved or incised images are petroglyphs. Occasionally these techniques were combined to produce painted petroglyphs. Prehistoric Native Americans produced most of the rock art found in Arkansas. We also have examples of historic Native American and historic Euro-American rock art. We do not use the term for modern graffiti, much of which, unfortunately, amounts to vandalism that causes harm to ancient or historic rock art sites. Where is it found? By our definition, rock art can only be made where there are bedrock outcrops or at least large exposed boulders. Such conditions are found throughout the Ozark and Ouachita mountain regions of Arkansas and in the intervening Arkansas River Valley. At present we know of only one rock art site in the Ouachita Mountains, but there are many sites in the Ozarks, a large number of them concentrated along the southern fringe and in the adjacent Arkansas River Valley. Visitors to Petit Jean State Park in central Arkansas may view excellent examples of prehistoric rock art at a site called Rockhouse Cave. What is it about rock art that we want to study? Studies of rock art in North America and other parts of the world address many topics. Here we list only a few that represent much of the current research. 1) Techniques and Technologies Rock art specialists want to identify the techniques and technologies used to produce rock art. How were pictographs and petroglyphs made? Careful examination reveals that some Arkansas pictographs were made by finger painting, while others were brush painted. Some petroglyphs obviously were produced by pecking away at a rock surface with a harder hammerstone. Others were engraved or cut into the rock, again using a harder implement. Sometimes the rock surface shows signs of preliminary preparation, such as chipping and abrading to remove bumps and provide a smoother working area.

Identifying the tools, pigments, and other materials used to create rock art depends on two kinds of information: first, identifiable traces of tool use that become part of the resulting rock art motif (e.g., finger or brush marks preserved in pictographs); and second, archeological discoveries of the tools themselves, often at or near the locations where rock art exists. Specialized analysis of pigment samples can identify the "recipes" of ancient paints used for rock art. Paints were made by mixing ground-up pigments (such as hematite, limonite, or charcoal) with a binder. Various techniques, including scanning electron microscopy and x-ray diffraction, have been used around the world to identify these minerals, and the same techniques could certainly be applied to Arkansas rock art. Identifying organic binders (such as blood, animal fat, egg, fish oil, and plant oils) using biochemical analyses is harder to accomplish, in part because these substances break down rapidly. Collecting paint samples for analysis is a destructive process. Specialists use extreme care to minimize the damage. Determining what techniques were used to produce rock art requires careful attention to the physical characteristics of each and every image at a very close range of observation. Weathering and other kinds of damage to rock art all too frequently compromise our efforts. We are constantly evaluating new procedures and equipment for studying rock art in the field. 2) Regional Styles

Defining regional style complexes is another topic of interest to modern rock art research. Archeologists have always used the form of material objects (projectile point shapes, ceramic and basketry designs, and so on) to draw the boundaries of "style zones" and "interaction spheres." The basic idea is that any given community uses certain material items to signal their identity. We do this today: our homes and automobiles signal membership in a certain income group; clothing may identify us by occupation or profession; dietary preferences and personal adornment suggest a particular subculture or ethnic group. Stylistic differences in archeological assemblages, manifested through time and across geographic space, reflect "archeological cultures" - that is, past communities of individuals who regularly interacted with each other and who shared particular stylistic preferences. By identifying rock art styles and analyzing their distribution, we can help assess style zones based on other classes of materials. 3) Cultural Boundaries Where regional style complexes are defined, modern scholars go a step further to ask whether these style zones coincide with geographical features or other environmental associations. What we call "archeological cultures" often are better understood as adaptations to local resources and environments. In other words, what we really have, often enough, is a set of implements—and an incomplete set, at that—used to get raw materials and basic commodities such as food, clothing, and shelter. It is very useful and enlightening to understand past adaptations, but it does not tell us everything about a past community's way of life. Multiple communities with distinctive social identities and belief systems might partake of very similar adaptations, thus masking much cultural variety in the archeological record. Projectile points and other artifact categories that often are the focus of stylistic analysis were made primarily for utilitarian purposes so, except in rare cases, "form followed function" and many point types had very wide distributions in space and time. Rock art, in contrast, seems to have been produced primarily for its representational qualities. For this reason, we hope that rock art style distributions may help trace more accurately the temporal and spatial boundaries of ancient cultures. 4) Dating Rock Art

Establishing the age of individual rock art elements and regional style complexes have been notoriously difficult, and one reason many archeologists have neglected rock art in the past. Sometimes we can place individual rock art motifs at a single site into relative order, if the images are superimposed, or if images on the same rock face display different degrees of weathering. Some images illustrate "datable" subject matter (i.e., mastodons must be Paleoindian; horses or firearms must be historic). When detached fragments of rock art, along with implements used to create the art, are excavated from datable archeological deposits, as happened during excavations at The Narrows in northwest Arkansas, then we can infer the age of rock art at the site from the dates obtained from the archeological deposits. Specialized techniques to measure the growth of lichens and biofilms left by organisms living in the rock surfaces, and the development of rock varnish (thin layers of material containing elements such as potassium and calcium) can provide an age for rock art—i.e., the images must predate the overlying substances. Recent experiments to obtain radiocarbon dates for rock art pigments, using a specialized technique called accelerated mass spectrometry, have produced the first direct age determinations of rock art images. We hope eventually to apply some of these techniques to rock art specimens in Arkansas. 5) Why It Was Made Perhaps the most intriguing area of interest is interpretation of the behavioral and ideological contexts of rock art and the social, cultural, or psychological functions of rock art sites. Archeologists think much (not necessarily all) rock art was linked with ritual activity. One fruitful line of inquiry is to study the sites as examples of individual (e.g., vision quests or puberty rites) versus community (e.g., shamanistic) ritual practices. Careful pictorial analysis of rock art subject matter — often in a comparative context of American Indian mythology — hopes to reveal aspects of the belief systems or worldviews of its makers. The placement of rock art sites, in terms of geographical context and relationship to other kinds of archeological manifestations (such as habitation sites, hunting areas, or ceremonial centers) is important to understand the overall cultural landscapes in which past communities carried out their quests for sustenance and a meaningful life. For example, isolation or difficulty of access may indicate that a site was considered "sacred space." On the other hand, rock art in sites also containing domestic refuse (such as The Narrows) argues for a more integrated social landscape in which ritual activity merges with recreational pastimes in the course of everyday domestic livelihood. All the issues discussed here require that rock art be considered within a regional archeological context. So what can rock art tell us about the past?

Archeologists are more and more interested in extending our studies of past human groups to include reconstructions not only of social, economic, and political arrangements, but of belief systems as well. This is a very difficult task. Past social, economic, and political arrangements often are reflected in the ways material objects were made, used, and subsequently disposed of. Belief systems tend to be more abstract and reflected more ambiguously and less directly in material objects. Yet, some material objects are (or contain) symbolic representations of the intellectual abstractions that make up a society's worldview. Many artistic renderings on portable objects such as pottery, cloth, or stone tablets, or on architectural constructions, portray elements of belief that may be more or less obvious (or, sometimes, completely indecipherable) to viewers. Interpreting or "decoding" these elements can be a daunting task, but not an impossible one when other information about the society is available. To reconstruct a belief system (whether wholly or in part), we must have an understanding of multiple elements and we must also understand the kinds of relationships that connect these disparate elements into a systemic whole. This challenging task can only be successfully pursued when we have a sufficient range of symbolic representations of a society's views. Rock art imagery, when we can connect it with a society's other material representations, becomes an invaluable source for studying past human experiences and the thoughts that guided or influenced the actions of our long-dead predecessors on this Earth. |