3YE25 Analysis

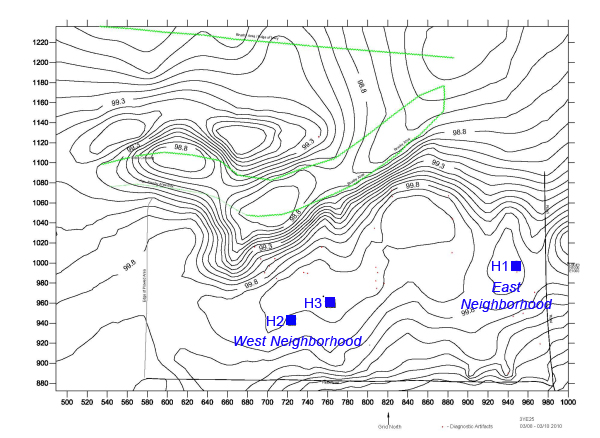

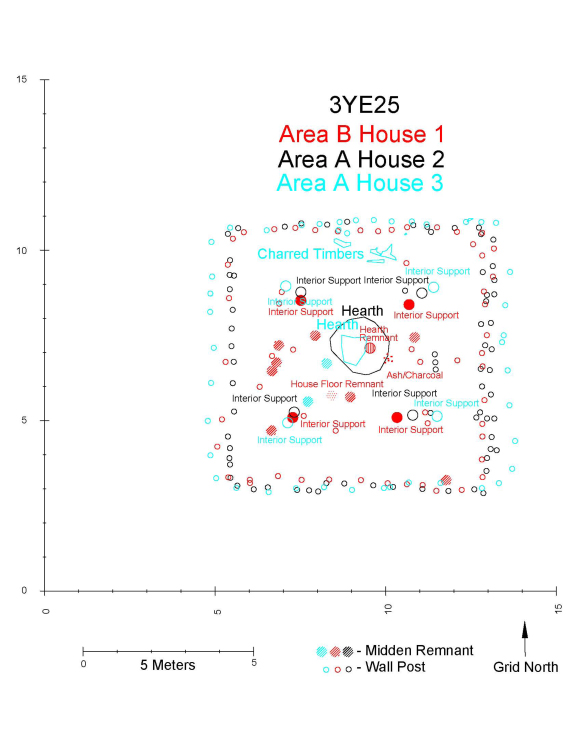

Analysis of House Architecture, by Jerry Hilliard Jerry Hilliard’s on going analysis of house architecture is producing fascinating insights about the Carden Bottoms phase community at 3YE25. Dr. Jami Lockhart’s archeogeophysical work at the site (reported last year) identified the buried remains of several houses at the site, organized into discrete neighborhoods. Last year we excavated two houses (Houses 2 and 3) in the western neighborhood and a third house (House 1) in the eastern neighborhood.

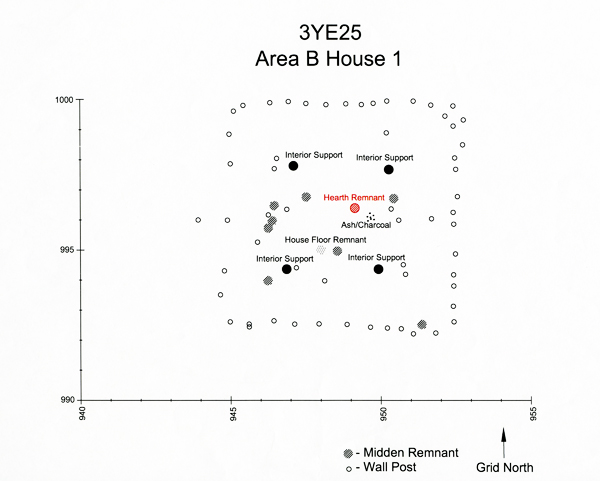

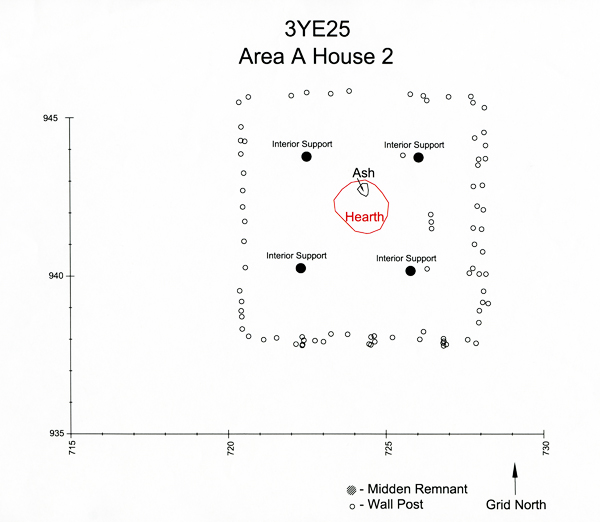

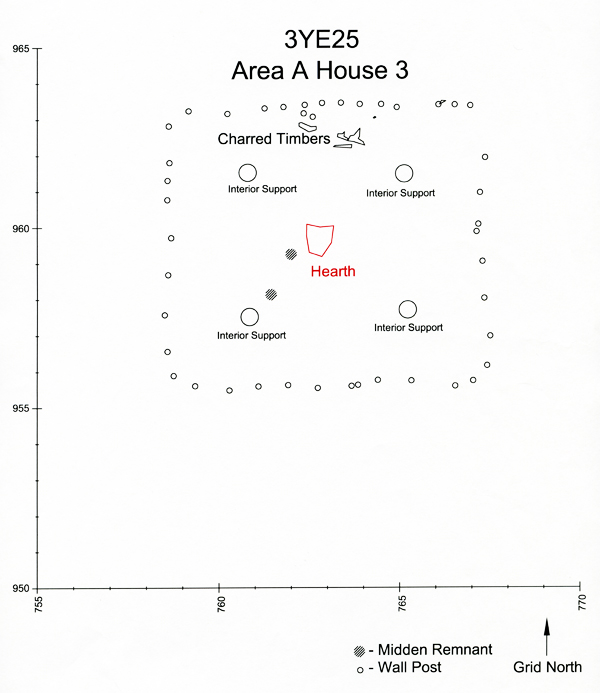

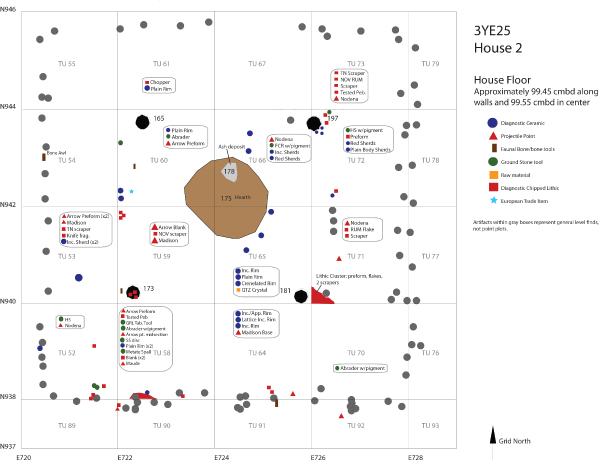

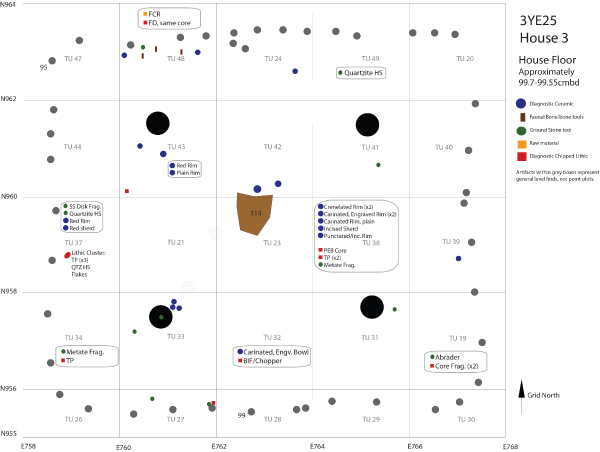

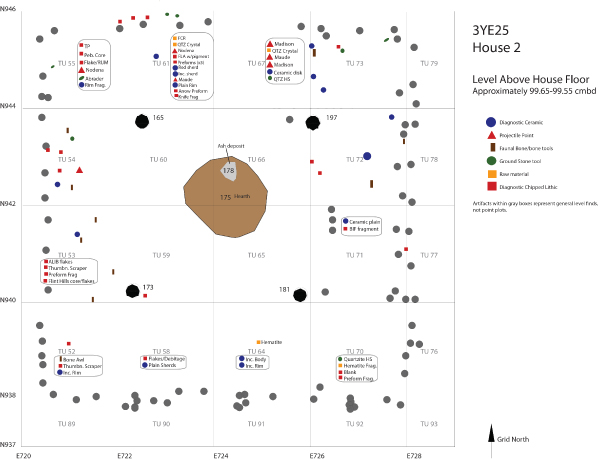

Hilliard’s study of the data we collected demonstrates that house construction began with the excavation of shallow pits dug into the compact and very fine-grained subsoil to provide a smooth, hard-surfaced floor. Four stout (25 cm diameter) roof support posts were then sunk into holes dug a meter below the floor surface, forming a four-meter square around the central, meter-wide hearth pit. Narrower wall posts were then embedded at short (30-40 cm) intervals along the outer edges of the house pit to form walls oriented to the cardinal directions. Gaps in wall post alignments suggest entryways opened to the east or west. Earthen berms extended part way up the exterior walls. The walls were not plastered with clay (our excavations encountered practically no hardened clay daub) and so must have been covered with thinner tree branch wattles, bark, or—most likely—woven cane mats. Bits of burned grass thatch retrieved in sediments above the house floors indicated that material was used to cover the roofs. The enclosed floor space of each house ranged from 7.5 - 8.5 meters on a side, and there is evidence in the form of internal post mold patterns for the construction of benches or platforms along the interior walls. Here are plan maps showing hearth and post mold features for the three excavated houses.

A remarkable finding is that all three excavated houses possessed nearly identical characteristics, as if they were built according to a common but detailed plan. Hilliard believes the houses were occupied year-round for one or perhaps two generations.

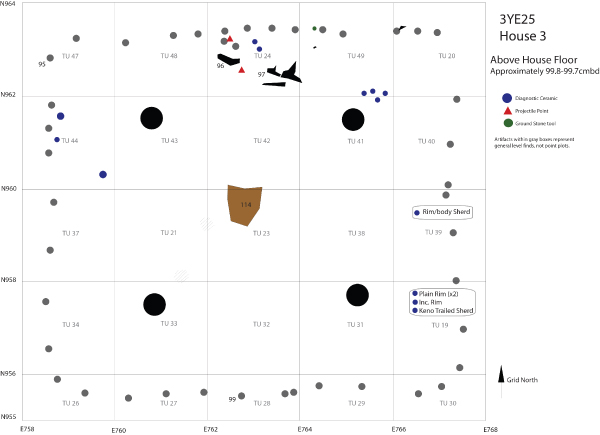

Artifact distributions within the houses are equally interesting. Artifacts found directly on the compacted floor surfaces include finished tools and fragments of broken pottery in the central areas surrounding the hearths, along with broken tools and discarded debris (including detritus from stone tool production and tool resharpening) clustered just inside the walls on floor areas that would have been beneath the interior benches.

But Hilliard also identified artifacts only along interior walls in the sediments above the floors, added during the destruction of the houses. These materials represent artifacts that most likely fell from interior lofts (used for the storage of food and equipment) and benches when the house was being dismantled.

The stout, deeply embedded interior support posts were certainly capable of carrying the weight of interior lofts. Hilliard suggests that these lofts my have been similar to those observed by members of De Soto’s army among the Tula Indians who lived south of modern Fort Smith. During a Spanish attack on a Tula village, Garcilaso de la Vega reported that a soldier named Francisco de Renoso Cabeza de Vaca “entered a house and ascended to an upper room that served as a granery ...” (Clayton et al. 1993, Vol. II:411).

Reference Cited: The De Soto Chronicles: The Exploration of Hernando de Soto to North American in 1539-1543. 2 volumes. Edited by Lawrence A. Clayton, Vernon James Knight, Jr., and Edward C. Moore (1993, The University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa). Carden Bottoms Ceramic Vessel Analyses, by Ann M. Early and Leslie C. Walker Ann Early has been analyzing manufacture and design characteristics on Carden Bottoms whole vessels in museum collections (University of Arkansas Museum Collections, National Museum of the American Indian, and Thomas Gilcrease Museum) to determine where those vessels were produced. Centering her analysis on Caddo vessels, readily identifiable based on the combination of vessel form and decorative treatment, Early found that 191 (23%) of the 841 vessels examined so far represent Caddo types. These numbers include the type Keno Trailed, which is commonly but not exclusively a product of Caddo pottery making traditions. Analysis of the compositional characteristics of pottery clays (see below) may help resolve questions concerning the cultural affiliation of the Keno vessels. Early’s analysis reveals more interesting findings. Most of the unquestionably Caddo vessels were made in southwest Arkansas at sites along the Ouachita and Red rivers, with the majority coming from communities along a small stretch of the Ouachita River between Malvern and Arkadelphia. Of these vessels, most also represent finewares, with comparatively few examples of utilitarian vessels. Examples of the earliest Caddo wares are absent in Carden Bottoms assemblages and while there are a few Middle Caddo finewares (possibly representing heirlooms) the majority of vessels are protohistoric (16th and 17th century) bottles and bowls. These findings raise interesting questions concerning the nature of the Caddo presence in the protohistoric Carden Bottoms community. The predominance of finewares suggests involvement in at least some measure of ritual activity.

Leslie Walker has been attempting to address such questions of community organization and ritual in her analysis of Carden Bottoms ceramics. Going beyond ceramic types and varieties, Walker is looking specifically at the artistic motifs that decorate ceramics and other objects. These objects can be divided into various production genres (for example, painted pottery, engraved pottery, basketry, rock art, etc.). Walker has been able to identify common artistic treatments applied to different material genres, such as painted pottery and rock art. She has also found that people living at Carden Bottoms, working in independent pottery-making traditions (e.g., Mississippian and Caddo) and in a variety of media (pottery and rock art), were participating in the production of a common style that symbolically reflected linked social relationships within a multiethnic community. It is likely that these relationships were maintained at least in part by ritual activities involving the production of rock art at specially selected places on the local landscape. Critical to both Early’s and Walker’s interpretations is verification of the locations where vessels found at Carden Bottoms sites were actually manufactured. To address that question, graduate student Rebecca Wiewel acquired support this year from the University of Missouri Research Reactor for training and access to their facility for ceramic compositional analysis employing instrumental neutron activation analysis (INAA). Wiewel and Sabo submitted an application to the National Science Foundation for a doctoral dissertation improvement grant to provide funding for this analysis, which we hope to undertake during the coming year. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|