The Caddo Indians

by Ann M. Early The Caddo lived in several tribal groups in southwest Arkansas and nearby areas of Texas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma from A.D. 1000 to about A.D. 1800. When visited by Spanish and French explorers around 1700, they were organized into three allied confederacies, the Kadohadacho on the great bend of the Red River, the Natchitoches in west Louisiana, and the Hasinai in east Texas. The Cahinnio, who were allies of the Kadohadacho, lived along the Ouachita River. Each confederacy was made up of independent communities, but all had similar languages and customs.

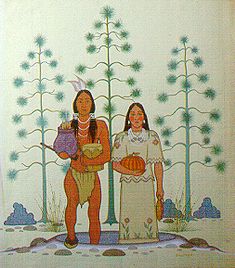

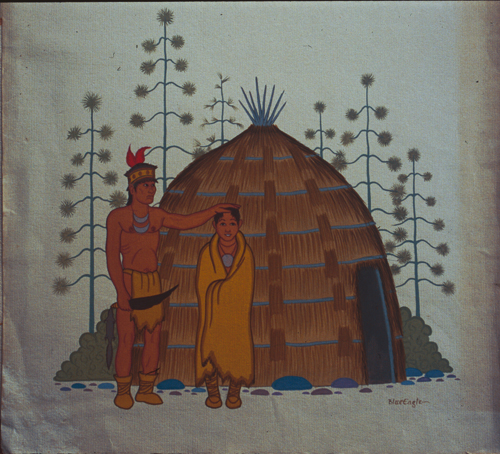

The Caddo were sedentary farmers who grew corn, beans, pumpkins, squashes, watermelons, sunflowers, and tobacco. Hunting for bear, deer, small mammals, and birds was important, as were fishing and gathering shellfish, nuts, berries, seeds, and roots. People who lived on the edge of the plains also hunted bison in the historic period. Bows, commonly made of Osage orange, or bois d'arc, wood, and stone or bone-tipped cane arrows were normal hunting equipment. People living near saline marshes or springs made salt by boiling brine in large shallow pans. Salt was used with food and was traded, along with bear oil or lard, bois d'arc bows, animal skins, and other goods to other Indians and European settlers. Horses and captives were also traded to the French for European goods in the early historic period. The Caddo also made elaborately decorated pottery vessels until metal and ceramic replacements were acquired from traders. Men typically hunted, held most civic and religious roles, and were involved in warfare. Men and women shared some tasks in preparing gardens and building houses. Raising children, tending gardens, making food and clothing, preparing skins, and weaving mats were primarily women's work. During celebrations and ceremonies, each gender occupationally had its own special activities as well. Before trade clothing became common, men wore breechcloths and moccasins with deer and bison skins added in winter. Women wore deerskin or woven skirts. In warm weather they went topless, and they wore a skin wrap in winter. Deerskin shirts with colored and beaded designs and fringes were sometimes worn by both sexes, and other elaborate deerskin garments were used on ceremonial occasions. Both men and women also decorated their bodies with painting and tattooing. Women in particular sometimes tattooed their faces, arms, and torsos with elaborate designs. Men had several hairstyles; the most common was short with a long braided or otherwise decorated lock. Women wore their hair long and braided or tied close to the head. Communities consisted of widely dispersed households separated by garden plots and woodlots. Each household or farmstead consisted of dwellings and work areas for one or more closely related families. The size, shape, and number of dwellings varied. Some houses were circular, conical, and covered with thatch. Others were oval or rectangular, made of timber stuck vertically into the ground and daubed with mud, and roofed with thatch or bark. An elevated corncrib, outdoor work platform, and upright log mortar for pounding corn usually stood near the dwelling. Inside the house were sleeping and storage platforms where baskets and supplies were kept, and a central fireplace. Woven mats, made usually by women and often elaborately decorated, covered floors and benches, and were important ritual items. Each community also had at least one temple or religious building, originally on an earthen platform mound, where sacred objects were kept and the most important rituals were performed. Society was organized by households and clans. Social position, marriage prospects, and some political roles were based on clan membership. Political leaders of the community, tribe, and confederacy were a ranked set of offices, with a priest, or xinesi, holding the highest civil and religious position in the confederacy. Other leaders took care of various secular or sacred activities, and one group, shamans or connas, performed a variety of rituals and treated illnesses.

The Caddo world was populated by many supernatural beings who had varying degrees of importance and power, with a supreme being, Ayo-Caddi-Aymay, having authority over the others. A series of rituals performed to ensure favorable relations between people and these supernatural beings and forces organized the annual cycle of life. These included a springtime planting ceremony, an 'after harvest' ceremony in the fall, and numerous ceremonies to commemorate birth, death, warfare, housebuilding, and other important individual and community events. The multilayered organization of Caddo society provided a way to interact with Europeans. When European travelers approached, they were usually met along the path by a contingent of greeters from the community. The travelers would be escorted to the dwelling of the caddi, the community leader, or to a special structure, and be seated in a place of honor. Here community leaders shared with the Europeans a smoke of tobacco from a calumet-an elaborately decorated pipestem and bowl, which created a bond of friendship that extended to all members of the respective communities. In this way the Caddo recognized the relationships among different members of their own confederacy, and they were able also to incorporate Europeans within their hierarchically organized society. The Caddo were important trading partners and allies of both France and Spain during the colonial era. However, epidemic diseases; competition and occasional hostilities with the Osage, the Cherokee, and the Choctaw; and the westward spread of American settlement eventually encroached on their domain. The Ouachita valley communities moved shortly after A.D. 1700, the last Red River communities were abandoned in the late 1700s, and in the nineteenth century most Caddo were forced to move first to Texas and then to reservations in Indian Territory. A large number of Caddos now live near Binger, Oklahoma, where their modern tribal center is located. Bibliography Newkumet, Vynola B. and Howard L. Meredith Sabo, George III Swanton, John R. |

||||

|

|