The Chickasaws

by George Sabo III According to their origin story, the Chickasaw people migrated from west to east, following a sacred leaning pole they set up every day. When the pole finally stood erect, the migration ended. The place where they had arrived was in present-day Mississippi, in the northern part of the state between the headwaters of the Tombigbee and Tallahatchie Rivers.

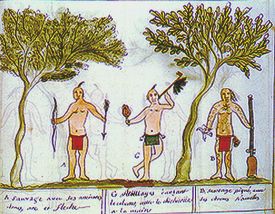

Evidence from historical and archeological studies also suggest that the Chickasaws split from a larger group that once included the Choctaws, with whom they share many linguistic and cultural features. When this split occurred has not been accurately determined. At the time of European contact, the Chickasaws controlled a large region astride the Mississippi River, extending from Ohio on the north to Mississippi on the south, and from the Mississippi River eastward to the Tennessee-Cumberland River divide. Their first recorded encounter with Europeans took place when Hernando de Soto established his 1540-41 winter camp at the town of Chicaza. Relations between the two groups remained tense throughout the winter, culminating in a Chickasaw attack on the Spaniards in early March, which inflicted very heavy damage and thoroughly demoralized the troops. Soto was forced to move his camp and the Spaniards spent nearly two months recovering and refitting their equipment before they were able to move on. The Chickasaws remained undefeated in battle throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, successfully withstanding assaults from both European and other Native American adversaries. During the 17th and 18th centuries, the Chickasaws occupied four or five large, fortified villages located in the central part of their homeland. The villages consisted of residential areas divided into clan precincts, and open areas for social gatherings and ceremonial performances. Square, pole-frame houses with grass-thatched roofs were constructed in the residential areas. Summer dwellings had open walls or were covered with woven cane mats, whereas winter dwellings had clay-plastered walls. The Chickasaw economy, like that of most Southeastern groups, was based on corn agriculture supplemented by hunting, fishing, and gathering of various local resources. Participation in pre-contact trade networks provided the basis for subsequent participation in the English deer skin and slave trade. This activity brought the Chickasaws into a series of hostile relationships with their neighbors, many of whom not only were the subject of Chickasaw slave raids but were also allied with the French (and, later, the Spanish) occupants of Louisiana territory.

Useful descriptions of Chickasaw social and ceremonial organization come from the journals of the English military officer Thomas Nairne, who led a 1708 expedition from Charles Town to the Mississippi River that passed through the Chickasaw country. From Nairne we learn that Chickasaw towns each had a chief whose authority extended mainly to internal community affairs. Councils comprised of the heads of several clans advised the chiefs. Upon the death of one of these chiefs, his counterparts from the other villages would gather to conduct an elaborate funeral ceremony lasting for several days, at the conclusion of which the heir — his sister's son — took over the office. Apparently even more powerful were the military officers, whose authority over warriors gave them control over the external affairs of the village, which were of much greater consequence than were the internal village affairs. The single most important event in the Chickasaw year was the Green Corn ceremony, which served both as a consecration rite to bless the new crops and as a renewal ceremony to reinforce intervillage ties. Disagreements between villages that cropped up from time to time were often settled by vigorous stickball games. In the 19th century the United States government forced the removal of Chickasaws from their Mississippi homelands during the infamous "Trail of Tears" march to Indian Territory. The Chickasaws persevered on their southcentral Oklahoma reservation, and today the Chickasaw Nation provides a variety to cultural, economic, educational and social services to its 35,000 members. Bibliography Gibson, Arrell M. Johnson, Jay K. Nairne, Thomas |

||||

|

|