Tunica and Koroa Indians

by George Sabo III When Hernando de Soto and his army approached the eastern bank of the Mississippi River in the spring of 1541, he visited towns of a native province called Quizquiz (pronounced "keys-key"). These Indians spoke a dialect of the Tunican language. At that time, Tunican speakers, represented mainly by the Tunica and Koroa tribes, occupied a large region extending along both sides of the Mississippi River in present-day Mississippi and Arkansas. How much of Arkansas was then occupied by these Indians is unknown, but French explorers and missionaries in the late 17th century reported Tunica and Koroa villages along the central and lower Arkansas River in eastern Arkansas, along the Ouachita River in south-central Arkansas, and along the Mississippi River south of its confluence with the Arkansas.

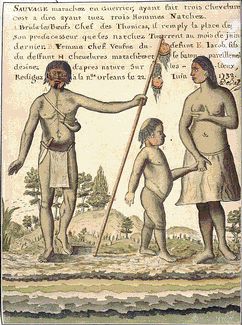

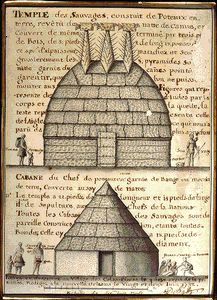

Tunica Indians were sedentary agriculturalists. Corn and squash were the primary food staples. The men did most of the gardening. The women collected wild plant foods, including fruits, berries, nuts, seeds, roots, and herbs. The men also hunted deer, bear, and occasionally buffalo for meat, hides, and other products. Water from salty springs was evaporated to make salt, some of which was traded to other tribes. The men wore deerskin loincloths during the warm seasons, and they tattooed themselves and wore beads and pendants. Women wore short, fringed skirts of cloth made by pounding the inner bark of mulberry trees. They also tattooed themselves and wore beads, pendants and ear ornaments. Women kept their hair in a single, long braid that often was coiled on top of the head. Both sexes wore cloaks of mulberry cloth, woven turkey feathers, or muskrat fur during the cold seasons. Spiritual beings and powers were recognized in many elements of nature. The cardinal directions along with the relative positions of the heavens and the earth represented the primary dimensions of the universe. The terrestrial world of humans, plants, and animals separated upper and lower worlds of spiritual beings. Tunica Indians believed that the sun was a female deity, and they recognized thunder and fire as important spiritual forces. Each village had a temple with a sacred fire where priests conducted rituals to maintain positive relations with spiritual beings.

Tunica villages consisted of circular dwellings arranged around an open area, or plaza, where the temple was usually located. Houses were built by setting a circle of upright posts into the ground. Horizontal cane stalks were woven through the uprights and a conical roof framework of wood poles was added. Walls were plastered with clay and roofs were thatched. Small doorways provided the only natural light in these houses and the only exit for smoke. One 17th century French explorer wrote that Koroa Indians decorated their dome-shaped houses with "great round plates of shining copper, made like pot covers." Outdoor cooking hearths and aboveground grain storage bins were also built near each house. Feasts, dances, and games were held in the plaza. Villages had leaders who inherited their positions. Separate leaders were appointed to manage internal village matters and external affairs including warfare. Warriors gained honor for their accomplishments and could be identified on the basis of their distinctive tattoos. Individuals could elevate their social standing through success in other activities, such as trading with Indians from other tribes or with Europeans. Most Tunica Indians moved their villages to the lower Yazoo River in present-day Mississippi by 1699. Many Koroa Indians - who suffered population losses from European diseases - joined the Tunicas, while other members of this group joined the Chickasaw and Natchez tribes. By the early 19th century, most Tunica Indians joined with Biloxi Indians living near Marksville, Louisiana, where today approximately 200 members of the Tunica-Biloxi tribe live. Bibliography Brain, Jeffrey P.

Jeter, Marvin D. Kidder, Tristram R. Sabo, George III |

||||

|

|