Woodland Period Cultures: Village Farmers

600 B.C-A.D. 900 by George Sabo III

Rock art, both petroglyphs (carved) and pictographs (painted), occurs at many archeological sites that have bedrock outcrops or large boulders. Motifs representing human, animal, bird, and insect figures, and also geometric and abstract forms correspond to Woodland and Mississippi period designs on portable artifacts such as pottery. Archeologists believe most rock art was made as part of individual (e.g., vision quest) and group (e.g., thanksgiving and renewal) rituals performed to create and maintain relationships between humans and the spirit world.

The increased reliance on plant food production affected Woodland settlement and land-use patterns. A good example of this was documented in excavations by George Sabo and Randall Guendling at the Dirst site along the Buffalo River in north-central Arkansas. The site was occupied intermittently during the Dalton, Late Archaic, and Early Woodland periods by groups of seasonally mobile hunters and gatherers. The site was then occupied between A.D. 600 and 900 by a sedentary Late Woodland community that supported itself by deer and elk hunting, fishing, nut and wild fruit gathering, and garden cultivation of chenopodium, little barley, maygrass, knotweed, squash, and corn. The Dirst site location was strategically located to assure access—even under periodic flood conditions—to small, dispersed bottomland habitats containing the only fertile soils in the region. The Dirst site occupants also experimented with making and using shell-tempered pottery vessels. “Tempering” means adding some substance to the clay to give it body and make it stronger. Earlier Woodland pottery was grit tempered using sand or crushed rock. Shell tempered ceramics can better withstand the thermal shock of direct exposure to fire. This new type of pottery was a handy development relative to the increased use of dried grains in the diet, which require prolonged boiling. Excavations at the Dirst site also provided information on changes in dwelling architecture. The Early Woodland occupants of the site constructed light, circular pole frame dwellings. The Late Woodland occupants built more substantial square structures with internal hearths and food storage pits.

Hopewell artists applied extraordinarily complex compositions to a variety of objects including sandstone tablets, ceramic vessels, and cut-out mica sheets. Some of these artifacts illustrate birds and other animals possessing unusual characteristics, indicating they were conceived as supernatural rather than ordinary creatures. Stone and ceramic smoking pipes were another medium for depicting animals, birds, and insects. Most of these are naturalistic but some also incorporate extraordinary features symbolizing supernatural qualities. These examples show how Hopewell artists gave explicit recognition to the importance of the spirit world in the realm of human affairs. In addition to these portable objects, Woodland Indians invested enormous amounts of labor in the construction of hundreds of monumental earthworks. Among the more famous are the Serpent Mound and Newark Earthworks in Ohio. The sinuous Serpent Mound is an effigy of a huge serpent extending for nearly a mile. The Newark Mound consists of gigantic geometric enclosures oriented to tracks inscribed across the sky by the paths of the moon, and suggests the emergence of a new concern with the link between human activities and cyclical movements of heavenly objects thought to represent important spirit beings or supernatural forces. Hopewell ceremonialism spread into many areas. Participants built thousands of effigy and burial mounds across eastern North America. The influence of Hopewell ceremonialism in Arkansas was seen at the Helena Mound site, near the confluence of the Mississippi and St. Francis rivers. (The site no longer exists.) Here, several community leaders and their heirs were buried in massive log tombs covered by conical-shaped earthen mounds. One of the burials was of an adolescent female whose grave goods included a copper and silver covered panpipe, copper ear spools, a drilled wolf canine and shell bead belt, and pearl and marine shell bead armbands, bracelets, and necklaces. In addition to burial and effigy mounds, some Middle Woodland communities constructed ceremonial centers containing mounds and earthworks that served to demarcate sacred space. Robert Mainfort conducted extensive studies at the Pinson Mounds near Memphis, Tennessee, where Middle Woodland communities built a dozen mounds within a 160-hectare area. The largest mound was a flat-topped, pyramidal structure 22 meters tall. Mainfort found no evidence of structures built upon its surface. Nor did he find any evidence of permanent occupation at the site. It appears that the Pinson mound center was used by local groups who gathered on special occasions to perform collective rituals in a specially constructed landscape.

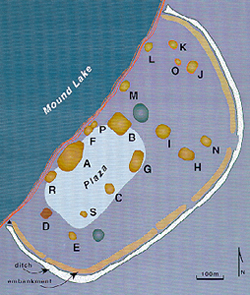

Excavations confirmed the presence of buildings on at least some of the platform mounds at the Toltec site. Additionally, several mound and embankment features at Toltec form an astronomical observatory, aligned to the solstice and equinox positions of the rising and setting sun. This suggests that the Plum Bayou people, like their Middle Woodland predecessors, attached importance to synchronizing their own activity cycles with the cyclical movements of heavenly objects. Thus, Woodland era culture has many continuities with earlier traditions, as well as striking elaborations, some of which introduced novel applications of art into belief systems and associated rituals. This new vision of the world went beyond the “naturalistic” portrayals of the Archaic period. In Woodland art, spirit beings are depicted as living creatures possessing extraordinary characteristics. A growing concern to integrate human activities within a larger cosmological system is seen in the earthworks—constructed in geometric and animal forms—that shaped Woodland landscapes and served to connect earthly activities with the cyclical movements of heavenly objects. Through time, the success and continued growth of these Late Woodland communities led to unprecedented levels of social and cultural complexity, giving rise to the Mississippian cultures of the late prehistoric era.

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

| Home | How do we learn about the past? | Indians Before Europeans | First Encounters | Historic Arkansas Indians | Indians After Europeans | Current Research | Writing Prompts | Learning Exercises | Project Background and History | |

|||||||||||||||

|

|

Last Updated: March 18, 2009 at 9:27:45 AM Central Time

|