Locals

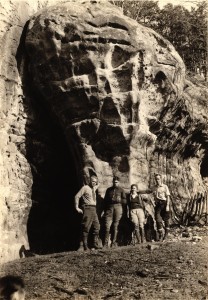

Local residents of the Ozarks have long known about the Native American artifacts found in the bluff shelters. In part this is because they too made use of the shelters in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Archeologists working in these sites often find evidence of their use as barns, areas for stills, and occasionally even dwellings. Moonshiner Cave in Devil’s Den State Park is one example of a bluff shelter that was converted into a building in the early twentieth century.

The first professional archeologists in the area were guided to these sites by local collectors and land owners. Even in the early 1920s when Mark R. Harrington, an archeologist working with the Heye Foundation, visited, he found evidence of digging in the shelters. He cites 1872 as the first time a white settler in the region found and recognized the presence of Native American textiles in the shelters, but it was likely earlier.

Harrington

Harrington, who worked for the Heye Foundation, now the National Museum of the American Indian, first visited Arkansas in 1916 but did not visit the Ozarks until the early 1920s. Harrington collected artifacts from at least 24 shelters in the region. These artifacts are housed at the National Museum of the American Indian and are available for study by researchers. Harrington used excavation techniques that were common at the time but which do not meet modern standards. This can make early collections challenging for modern archeologists. Most of his focus was on collecting artifacts suitable for display in museums with a particular focus in the Ozarks on the perishable artifacts such as textiles and baskets found in dry shelters and caves.

Harrington kept field notes but never published on his findings in the Ozarks until many years after his excavations. He published a monograph in 1960 through the Heye Foundation compiling his field notes and interpretations. He outlined what he thought were two cultures that occupied bluff shelters in the Ozarks—the “Bluff-Dwellers” and the “Top Layer Culture.” Modern scholars have abandoned the idea of a separate “Bluff-dweller” culture, but Harrington’s work was the starting point for understanding the culture history of the region.

Dellinger

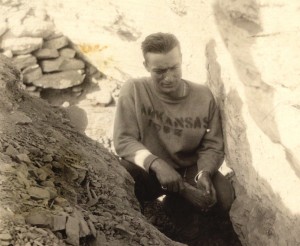

The next major figure in the archeology of Arkansas Ozark bluff shelters was Samuel Dellinger. Dellinger became the curator of the University of Arkansas Museum in 1926. Although he was trained as a zoologist, he saw the importance of archeology in the region and began a program of excavations in Ozark bluff shelters between 1931 and 1934. Dellinger started this program in part to keep the materials in the state for study. There was increasing interest in these sites by researchers from other institutions, and Dellinger wanted the University of Arkansas to be involved in collecting artifacts to ensure that they remained accessible for study in the state rather than at eastern institutions.

While Dellinger was not himself a trained archeologist, he did consult with the prominent archeologist Carl E. Guthe about field methods before embarking on his program of bluff shelter excavations. Dellinger sent a series of recent graduates and current students—such as Wayne Henbest, Charles Finger, James Durham, and Tom Millard—to oversee the excavations at 85 sites. Excavations were supported by a grant from the Carnegie Foundation and donations from prominent Arkansans such as Harvey Couch, a major figure in the electrification of Arkansas.

The result of this project was 20 books of notes taken in the field and an amazing collection of material, much of it well preserved perishable items not found on most archeological sites. The Dellinger notes and collections are a great resource for current scholars, but they are not without their problems. Much has changed in the field of archeology since the 1930s. Knowledge of both field methods and culture history has increased. This can lead to frustration in modern researchers who wish for more precise contextual information about the artifacts that were found. While “stuff” is cool, the real information to be gained by archeologists is more often found in the location of the artifacts in relation to each other or in relation to geographic or geologic contexts.

The collections made by Dellinger’s crews are preserved in the University of Arkansas Museum Collections. While these collections are no longer on display to the public, they are still available for researchers to study.

Dellinger, following Harrington’s lead, interpreted the material from the bluff shelters as belonging to two different cultures. The earlier culture they called the “Bluff-dwellers” and the later culture the “Top-layer Culture.” This interpretation has largely been abandoned by modern researchers who believe that the story of the peoples who used the shelters is more complicated than first thought.

Legacies of Early Archeology

Later research has been carried out by archeologists at the Arkansas Archeological Survey, researchers from other institutions, and by contract archeologists when sites have been impacted by federally funded projects. Researchers such as James and Sandra Scholtz, Gayle Fritz, Jerry Hilliard, Randall Guendling, Kathy Cande, Carol Spears, Mark Raab, David Stahle, Neal Trubowitz, David Jurney, George Sabo, and Elizabeth Horton have contributed much to current interpretations of prehistoric life in Arkansas Ozark bluff shelters. The work of these researchers is the basis for our discussion in the People and Examples sections of this website. You can find out more about their work in the Read More section.

These modern scholars have tackled the shelter materials in the Dellinger collections mostly by artifact type. For example, the faunal (animal bone) collections from the Dellinger excavations were studied as were the food plant remains. The perishable textiles have been studied as well. Likewise, rock art in shelters and along bluffs has been surveyed region-wide. Other, less extensive, work has been done looking at the stone tools and the ceramics in shelter collections.