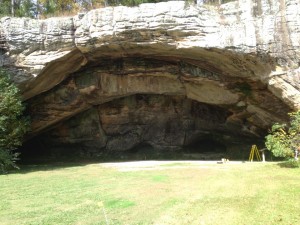

This shelter goes by many names which can cause some confusion. It is currently called “Indian Rock Cave” or “Indian Rock House,” and is located in the town of Fairfield Bay. Fairfield Bay did not exist before the 1960s and the closest town to the shelter when Dellinger visited it in the 1930s was Edgemont. He calls the shelter Edgemont in his notes and probably got the name from the local residents at the time. Because there are so many variations of Indian rock house cave, researchers usually call it Edgemont. No matter what name you call it, it is impressive as a geologic feature and contains some equally impressive rock art.

It is the most accessible of the shelters listed on this website because it is currently located on a golf course making it easy to walk to. The Log Cabin Museum which interprets both the shelter and early historic settlement in the region is located on top of the bluff line and is your starting point for visiting the shelter itself. The museum is located in the same parking lot as the Indian Hills Golf Course, so follow the signs for the golf course and park at the far end of the lot. From there you will see the museum located in a reconstructed log cabin. The museum displays a handful of artifacts found in the shelter which were donated to the University of Arkansas Museum and are currently on loan to the Log Cabin Museum. The most interesting one is a small catlinite pipe which represents the late-period Native American occupation of the shelter.

After you check out the museum you can access the shelter in a couple of different ways. There is a short trail with some easy stairs that starts at the log cabin. You can also access the shelter from the golf course itself, and you may be able to arrange to be taken to the shelter using one of the Log Cabin Museum’s golf carts.

The site has been visited by several professional archeologists over the years beginning in the 1920s, but has never been professionally excavated. The only known artifacts from the site were collected by amateurs, and a few of these artifacts were donated to the University of Arkansas Museum in the 1940s. The site was operated as a for-profit tourist destination in the 1930s and tourists were allowed to dig. Later in the 1960s six feet of dirt were removed from the shelter with a backhoe. Because of this, very little is known about the archeology of the site. The few artifacts in the museum collection suggest that the shelter was in use from the Archaic period to the Late Mississipian, but because of the disturbance of the site not much more can be said.

Once you arrive at the shelter you will see a plaque installed by the Daughters of the American Colonists in 1934 which claims that De Soto visited this site. Current scholarship on De Soto’s route says that this is not true. De Soto did not visit the heart of the Ozarks, only getting as close as Batesville in the east and the Arkansas River Valley near Fort Smith in the west. However, the shelter is no less interesting as a site because of this. After all, the history of the place extends back almost 8,000 years.

The most spectacular feature of the shelter is the Native American rock art which is the reason this location is included on the National Register of Historic Places. Most of the rock art is located on the west side of the shelter. You can see several human figures depicted here as well as a four-legged animal of some variety. In addition to the human and animal figures there are a number of lines and geometric shapes. All the rock art in this shelter consists of petroglyphs rather than pictographs.

1930s photograph of some of the rock art in Edgemont Shelter.

1930s photograph of some of the rock art in Edgemont Shelter.