Goosefoot

(Chenopodium berlandieri)

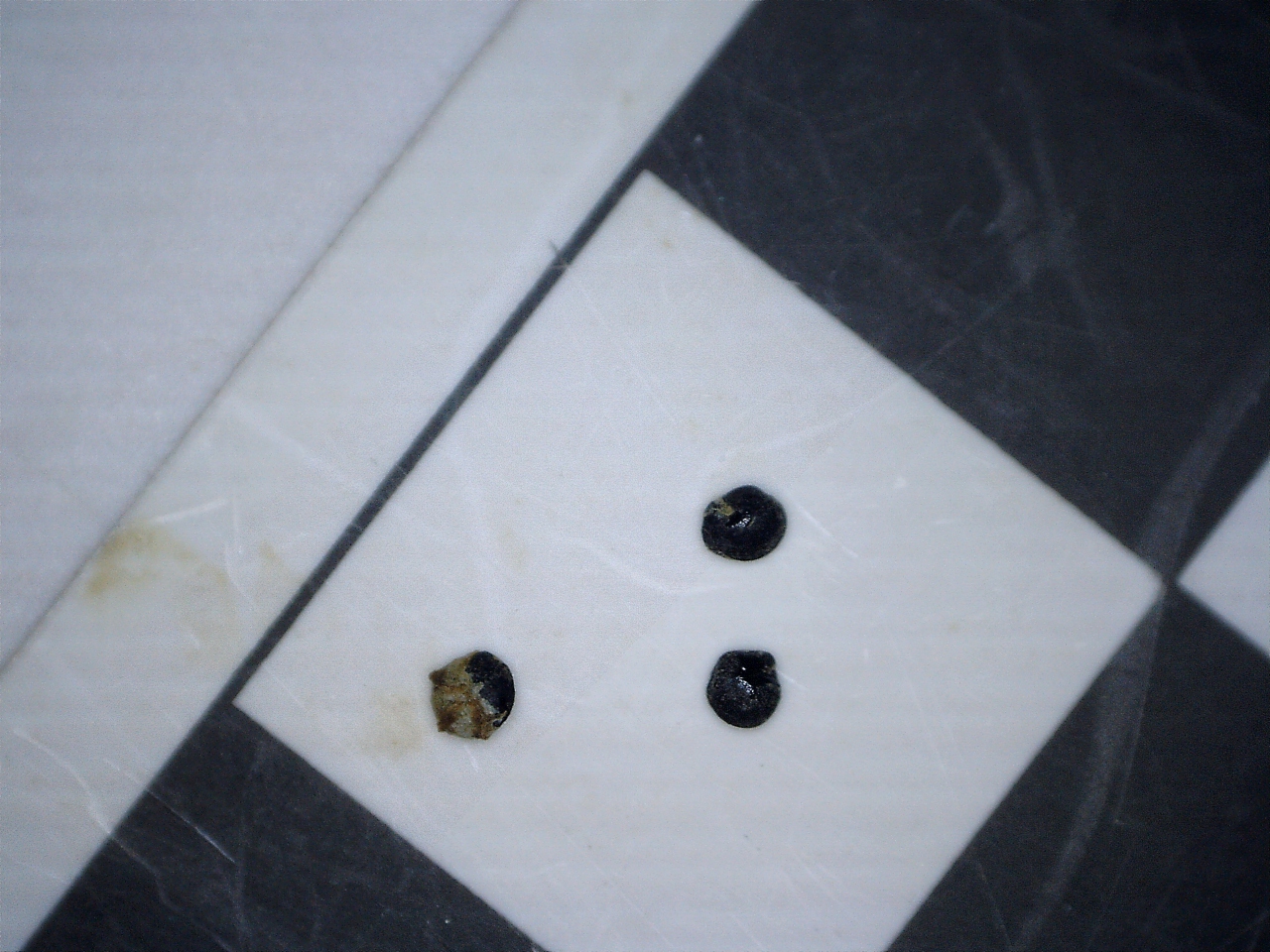

Goosefoot (Chenopodium berlandieri) is related to quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa– domesticated in South American) and resembles lambsquarter (Chenopodium album, a more commonly found relative) in appearance. A key in identifying Chenopodium berlandieri, particularly in the archeological record, is the distinctive pitted appearance of the seeds, hence its other moniker “pitseed goosefoot”.

The seeds are very small, only between 1 and 1.5 millimeters in diameter, so it may seem surprising that these starchy seeds were an important dietary component for Indigenous people living in eastern North America. Researchers have found that the energy provided by these small seeds is comparable to modern staple foods like corn and rice (Gremilion 2004).

About 5,000 years ago, people began intentionally planting goosefoot, although wild goosefoot had been gathered for food long before. Chenopodium berlandieri was domesticated by people living in the Eastern Woodlands almost 2,000 years ago. The domesticated goosefoot, Cheonopodium berlandieri ssp. jonesianum is differentiated from the undomesticated Chenopodium berlandieri based on the thickness of the outer seed coat (Muller et al. 2017).

Goosefoot starts to sprout in May or early June.

Goosefoot flowers are not particularly showy. They are green, tightly packed clusters.

Goosefoot seeds appear in late summer.

The leaves of goosefoot are edible. Although they contain oxalic acid, they can be eaten moderation, especially when cooked.

Goosefoot flowers in mid to late summer.

Chenopodium berlandieri- pitseeded goosefoot- is distinctive from other goosefoot species in that their seeds are textured with small pits (hense the nickname).

These small seeds can be soaked overnight to remove saponins (bitter-tasting compounds present in the seeds) , then cooked into porridge or ground into flour.

Goosefoot leaves are alternate and can vary in shape, but are generally elongated with the lower leaves being largest and more toothy, while the upper leaves often have smooth margins.

Goosefoot plants have a fairly bushy form, although they can get fairly tall.

Goosefoot References

Asch, D. L., and N. B. Asch

1977 Chenopod as Cultigen: A Re-evaluation of Some Prehistoric Collections from Eastern North America. Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology 2:3-45.

1985 Prehistoric Plant Cultivation in West-Central Illinois. In Prehistoric Food Production in North America, edited by R. I. Ford, pp. 149-203. Anthropological Papers No.75. Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Fritz, Gayle J.

1984 Identification of Cultigen Amaranth and Cheonopod from Rockshelter Sites in Northwest Arkansas. American Antiquity 49(3):558-572.

1990 Multiple Pathways to Farming in Precontact Eastern North America. Journal of World Prehistory 4:387-435.

Fritz, Gayle J. and Bruce D. Smith

1988 Old Collections and New Technology: Documenting the Domestication of Chenopodium in Eastern North America. Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology pp. 3-27.

Gilmore Melvin R.

1931 Vegetal Remains of the Ozark Bluff-Dweller Culture. Papers of the Michigan Academy of Science, Arts, and Letters, Vol. 14:83-102.

Gremillion, Kristen J.

1993 Crop and Weed in Prehistoric Eastern North America: The Chenopodium Example. American Antiquity 58(3): 496-509.

Kindscher, K.

1987 Edible Wild Plants of the Prairie. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence.

Muller, Natalie G., Gayle J. Fritz, Paul Patton, Stephen Carmody, and Elizabeth T. Horton

2017 Growing the lost crops of eastern North America’s original agricultural system. Nature Plants 3:1-5.

Smith, B. D.

1992a The Economic Potential of Chenopodium berlandieri in Prehistoric Eastern North America. In Rivers of Change: Essays on Early Agriculture in Eastern North America, edited by B. D. Smith, pp. 163-183. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

1992b The Role of Chenopodium as a Domesticate in Premaize Garden Systems of the Eastern United States. In Rivers of Change: Essays on Early Agriculture in Eastern North America, edited by B. D. Smith, pp. 103-131. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

Smith B. D., and C. W. Cowan

1987 Domesticated Chenopodium in Prehistoric Eastern North America: New Accelerator Dates from Eastern Kentucky. American Antiquity 52:355-357.

Smith, B. D., and V. A. Funk

1985 A Newly Described Subfossil Cultivar of Chenopodium (Chenopodiaceae). Phytologia 57:584-587. Wilson, H. D.

Wilson, Hugh D.

1981 Domesticated Chenopodium of the Ozark Bluff Dwellers. Economic Botany 35:233-239