Jodi A. Barnes, UAM Research Station

Artifact of the Month - November 2019

Rusty pieces of metal are important artifacts too! In 2013, when archeologists conducted a metal detector survey at Camp Monticello, a World War II Italian prisoner of war (PoW) camp in southeast Arkansas, they recovered lots of nails, hinges, and metal fragments. In the lab, they cleaned, counted, and catalogued those 20th century artifacts. When Dr. Barnes, the ARAS-UAM Research Station archeologist, cleaned this piece of galvanized metal, she thought, “yay, another piece of rusty metal!” But once the artifact was clean, she noticed the etchings that a prisoner of war carved into it. This scrap of metal tells a story of a PoW’s creativity during war. It is also an important reminder of the importance of sites like Camp Monticello for understanding Home Front Heritage in Arkansas and the United States.

Camp Monticello: A World War II Prisoner of War Camp

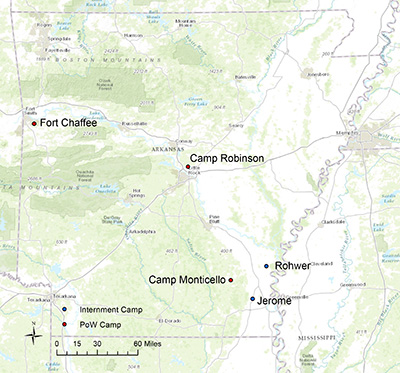

Home Front Heritage includes the places and landscapes of wartime mobilization that occurred in the United States between 1939 and 1945. Arkansas played an important role in World War II and the state has a unique Home Front Heritage. Not only did the state provide timber for war construction, they housed enemy prisoners of war and Japanese American internees. Initially, two facilities were constructed to house German PoWs (Fort Chaffee, near Fort Smith, and Camp Robinson, near Little Rock) and one (Camp Monticello) for Italians. There were also a number of smaller branch work camps located around the state. These camps were among about 125 main camps and 425 smaller branch camps for PoWs located across the country, as the early 1940s witnessed the unprecedented detention of an estimated 650,000 persons. Two Japanese American Internment Camps were also established in Arkansas—Rohwer and Jerome. In 1944, Jerome was closed and the Japanese American internees were transferred to Rohwer and other camps across the country. Jerome was then converted into a German PoW camp, and renamed Camp Dermott, becoming the third facility for German PoWs.

Archeologists are increasingly conducting research on PoW camps, internment centers, and their inmates. Michael R. Waters initiated the first investigation of a prisoner of war camp at Camp Hearne in Texas. Since then archeological research on internment has focused on the ways that the spatial arrangement, architecture, and material culture of such sites were structured according to the central principles of surveillance, discipline, and control, the everyday routines and work of PoWs, maintenance of individual and cultural identities, everyday resistance, and camp construction.

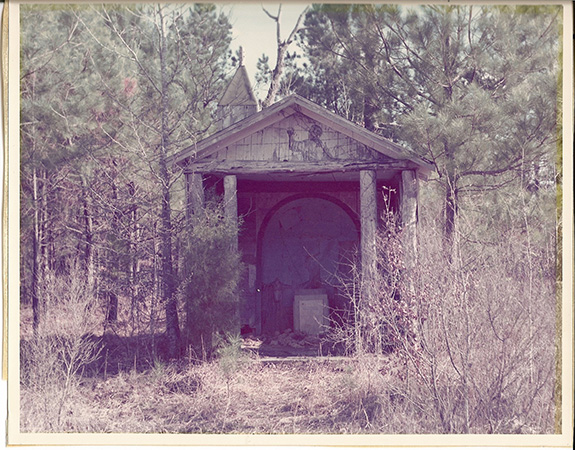

Today, Camp Monticello is located in an experimental forest owned by the University of Arkansas at Monticello. The buildings are gone, but old road beds and building foundations remain. Archival research was conducted at the UAM Library, the Drew County Historical Society, the Arkansas History Commission and State Archives, Special Collections at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville, and the National Archives in College Park, Maryland. This resulted in newspaper articles, a number of site survey, labor, and camp inspection reports, letters regarding the transfer of PoWs to and from Camp Monticello, menus, and clothing and equipment records. Arkansas Archeological Survey staff, students, and volunteers with the Arkansas Archeological Society helped with the total station mapping and the metal detector survey of the Officer’s Compound and one of the enlisted men’s compounds. In addition to the galvanized metal fragment, nails, tacks with the tarpaper still attached, hinges, springs for doors, buttons, buckles, cologne or hair tonic bottles, toothpaste and shaving cream tubes, and a U.S. issued identification tag were recovered. These artifacts as well as the features on the landscape provide information about the camp construction and the daily routines of the Italian PoWs.

Creativity at Camp Monticello

In Italy from June 1940 through May 1943, hundreds of thousands of Italians went to war. By the end of 1943, over 600,000 of those Italian soldiers were taken prisoner and, of those, 50,000 were brought to the United States as enemy prisoners of war. The British captured much of the Italian high command at Tobruk and elsewhere in North Africa and many of these officers were put on ships to New York and then a train to arrive in southeast Arkansas at Camp Monticello, one of the few camps that housed both enlisted men and officers.

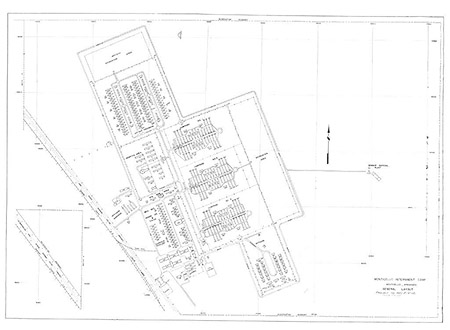

Camp Monticello is located south of Monticello in Drew County. Monticello’s rural location, advocacy by local civic leaders, and the need for labor in agriculture and the timber industries influenced the decision to locate the camp in the southeastern part of the state. The articles of the 1929 Geneva Convention regulated many aspects of the conditions within the PoW camps. The treaty stipulated that the PoWs should be treated the same as the troops of the retaining power. Therefore, Camp Monticello was built to the standards of American camps. Initially, PoW camps were placed within existing military reservations, but later, as the numbers of PoWs rose, camps were built on newly acquired land. Town-like camps were quickly built from military plans with basic one-story frame barracks, latrines, warehouses, mess halls, staff housing, medical facilities, and recreation areas arranged in grid layouts with open firebreaks and bounded by barbed wire fences and guard towers.

At Camp Monticello, PoWs were housed in different sections of the camp depending upon their rank. There were three compounds for enlisted men, one for officers, and one for generals. Prisoners also received monthly allowances and work assignments based on their rank—privates were required to work and do chores around camp; corporals or sergeants were required to work as supervisors; and officers and generals were exempt. Many of the PoWs opted to work outside the camp on farms or with timber companies. In the camp, PoWs worked as aids to generals, as interpreters, or in the hospital, mess halls, or PXs. This left many of the PoWs with lots of free time.

Article 17 of the Geneva Convention states: “So far as possible, belligerents shall encourage intellectual diversions and sports organizations by prisoners of war.” Since the majority of PoWs at Camp Monticello were officers and exempt from work assignments, athletics and recreational activities were important to alleviate the boredom of daily life. Inspection reports from Red Cross visitors indicate that the PoWs participated in a number of intellectual diversions. A film was shown once a week at the theater in the Garrison Echelon. Theater was popular; the PoWs wrote their own plays. They also formed an orchestra and performed in a converted barracks used as a concert hall.

The PoWs also made novel things out of wood, stone, cement, and metal. P. Schnyder, an International Red Cross representative, visited the camp in 1943 during an exhibition of paintings and sculptures executed by the prisoners. He describes the landscapes and portraits as particularly good, but he was most impressed with the miniature models of warships, officers’ barracks, and Santa Luca Church near Bologna. Reports indicate that the PoWs also decorated some of the chinaware in the mess halls and created an enclosure for birds in captivity. Excavations and archival research at other PoW camps have shown that prisoners attempted to regain some of their individuality through acquisition or creation of personal or unique items. For example, at Camp Hearne in Texas, archeologists recovered a canteen in which a PoW etched his travels from North Africa to New York City to Camp Hearne.