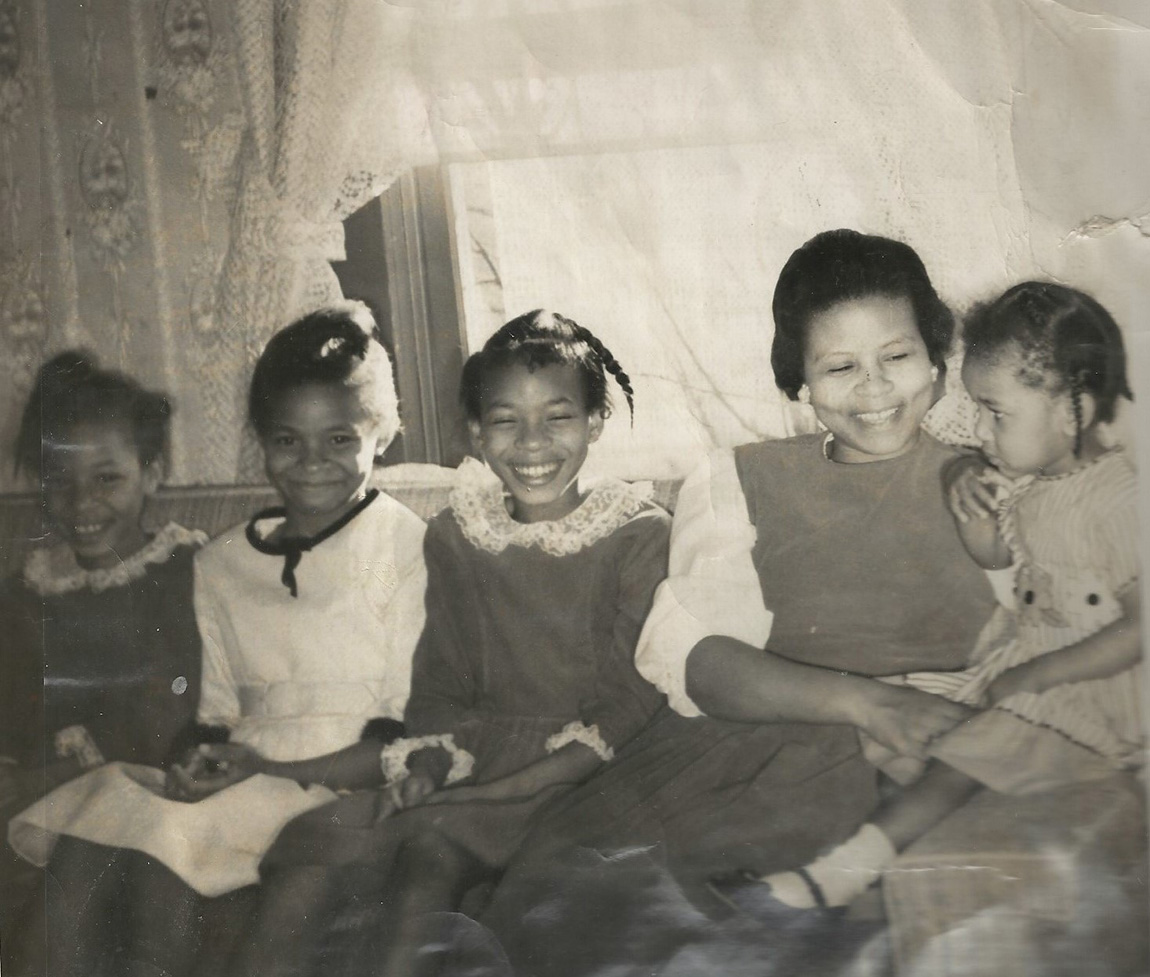

Azzie McGehee (second from right), who was born and raised on the Valley Plantation, with her daughters (left to right) Larance, Mary, Lois, and Carol circa 1962 (Courtesy of Mary McGehee)

Azzie McGehee (second from right), who was born and raised on the Valley Plantation, with her daughters (left to right) Larance, Mary, Lois, and Carol circa 1962 (Courtesy of Mary McGehee)

Matthew P. Rooney, ARAS-UAM Research Station

"Archeology is..." series - August 2025

Archeologists generally seek to understand people who lived in the past by studying the material residues of their lives—artifacts, ecofacts, structures, landforms, and any other human-made cultural creations. Another major task is collaborating with communities to construct that understanding of the past. These include Indigenous communities, local communities, and descendant communities. One of the ways to connect these communities with archeological projects is to perform genealogical research. This has been an especially fruitful avenue of study in my plantation research project in southeast Arkansas.

Before I put shovels or trowels in the ground at the Hollywood/Valley Plantation in Drew County, one of my first self-appointed tasks was connecting with African Americans who either grew up on the plantation or were descendants of those who grew up on the plantation. I started by going to local Black churches and was soon put in touch with people who were born and raised on the plantation in the 1930s and 1940s. When I first sat down to interview these people, I found that they framed their stories around their genealogy. They thought archeology was interesting and were happy to look at artifacts to help me interpret them, but they all expressed a greater desire to have me perform more genealogical research on their families.