Matthew P. Rooney, ARAS-UAM

"Archeology is..." series - December 2024

History with a capital “H” refers to an academic discipline that seeks to understand the past by using primary-source documents as evidence. Right away, one can understand how history is archeology in a literal sense given that human-created documents are also artifacts. Archeologists study the material residues of human culture, including artifacts, which they usually define as portable human-made objects. This oversimplification, of course, does not get at the nuances between the two disciplines and how they understand and interpret the past differently.

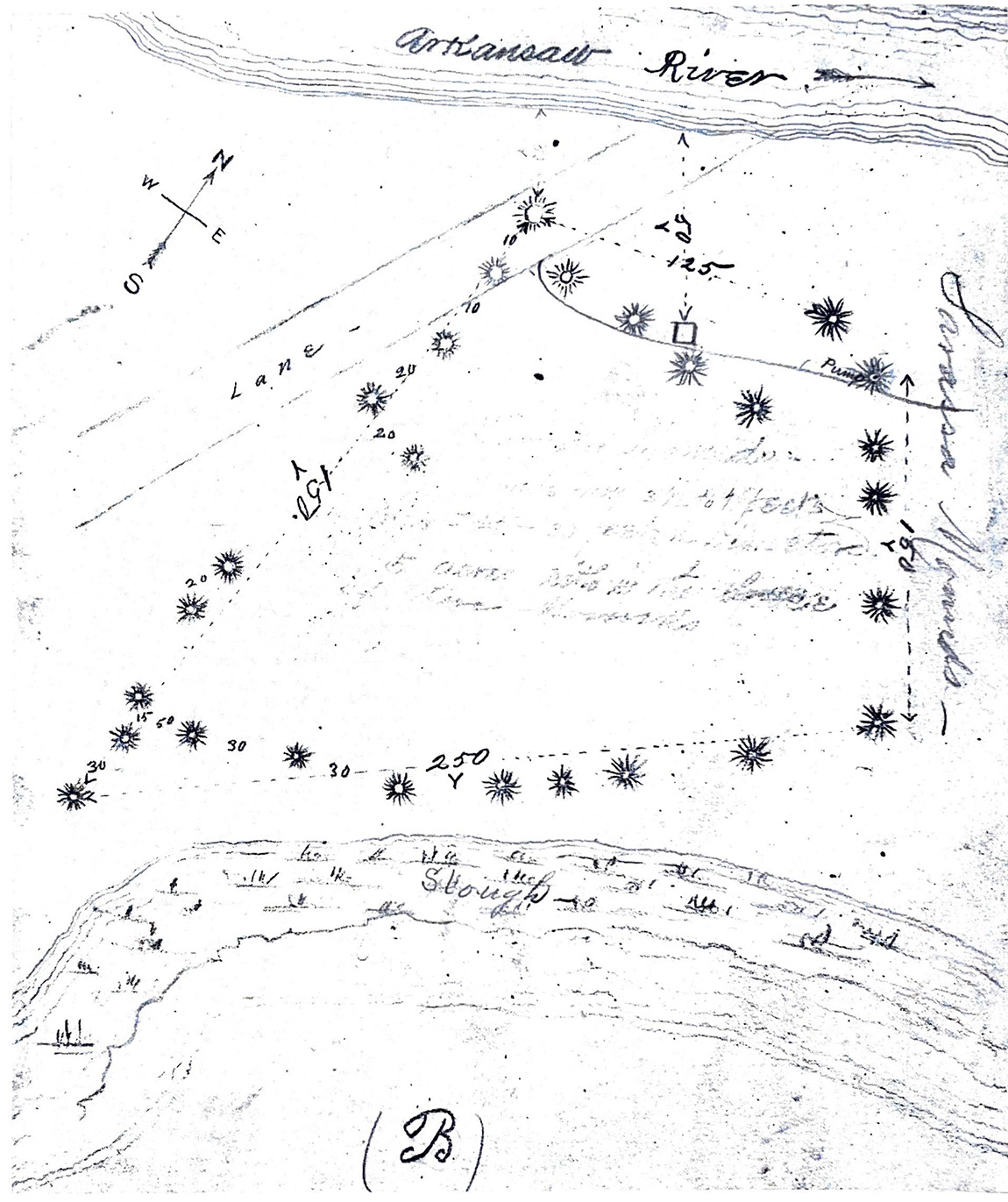

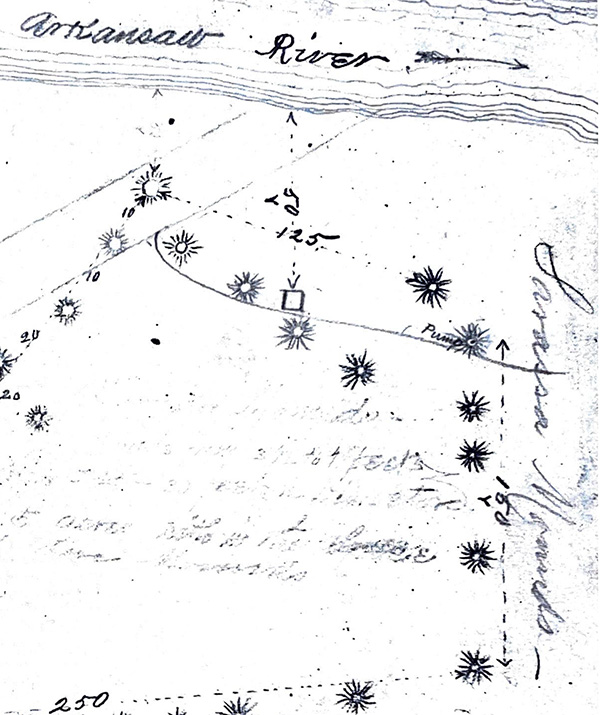

Historical scholarship is expected to be based on new textual discoveries that advance knowledge of the past and contribute some new understanding of how people lived. However, it is not a simple matter of finding words and interpreting them as truth. Specialty is needed to understand the inherent biases in documents. At a minimum, the historian should be able to understand and explain who created the documents, for what purpose, what these do and do not say, whose voices are missing, and the degree to which the authors were credible. This skillset is equally important for archeologists, all of whom rely on written documents even if their research focus is on people who lived long ago and did not use writing as a system of communication. Archeologists today must reference and incorporate information from myriad sources including historic maps, geological surveys, and reports from earlier archeologists—primary source documents that should be given the same discerning eye.

Archeological scholarship is typically based on analyses of objects and places created by, or associated with, humans in the past. Archeologists use a variety of scientific principles and techniques as well as statistical analyses to create and interpret datasets. At a minimum, archeologists are required to have specialized knowledge of geological assumptions such as the Law of Horizontality and the Law of Superposition, an ability to distinguish culturally modified objects and features from those that have resulted from non-human geological events and animal behaviors, and success in recreating past environments based on small samples of materials that happened to survive to the present. Historians have increasingly seen archeology as relevant to any understanding of the past given that it relies on deductive reasoning and evidence that is not mired in the subjectivities of historical authors. Taken together, all information derived from both research traditions tell a more complete and more holistic story, especially given that the voices missing from documents—particularly of those who were enslaved or killed—may be discernible in the archeological “record.”

Where history and archeology complement each other best is in the practice of the aptly named subdiscipline of “historical archeology,” which in North America refers to archeological inquiry focusing on any time during or after European colonial powers started to invade the Americas over 500 years ago. A distinction is made not simply due to the appearance of written narratives referencing people and places in the hemisphere for the first time, but more importantly due to the drastic change in global material culture that occurred as domesticated plants and animals—as well as material goods, diseases, and ideologies—rapidly moved across oceans and continents in both directions.

In 1541, Spanish conquistador Hernando de Soto invaded Indigenous communities in Arkansas with his army, which brought along alien weapons and armor made of iron, unfamiliar animals such as pigs and horses for food and transportation, a strange language distinct from any other heard before in that part of the continent, and a foreign Christian ideology. Such items, beings, and ideas stayed behind in various ways, long after the invaders fled to the Gulf of Mexico and were used by Indigenous peoples over the next several decades as their societies continued to create their own histories. Metal objects left behind by Soto’s army were not the only things to be scavenged and refashioned into tools and spiritual items—other goods and materials originating outside the hemisphere passed through trade networks and ended up in the hands of Indigenous people who had never laid eyes on a white European before.

Soto’s entrada included chroniclers who wrote down their observations, both during the invasion and in the following years. Historians and archeologists have spent decades studying and interpreting these documents as they are some of the earliest written accounts—the type of evidence favored by historians—that speak about the Spanish experience with Indigenous North Americans. This information continues to be used in tandem with archeological inquiry to understand the lifeways of Indigenous southeasterners, both before and after this European intrusion.

It must be understood, however, that these writings only discuss a time spanning a few years, and no further primary source documents were written about the various Indigenous Arkansans until French colonizers arrived 130 years later. If one were to rely on documents alone, the years 1543-1673 would only be a blank spot on the tapestry of history—and to a certain extent, unfortunately, this is how Arkansas’s past is understood. Many historical accounts of pre-removal Arkansans simply discuss the interactions with Soto and later Marquette and Jolliet with a major chasm between the two. Can you imagine reading a history textbook today that had nothing to say about the time in North America between 1764 and 1894? Between 1894 and 2024?

Ultimately, history is archeology, but archeology must be history too. If one wants to understand and interpret the past, there should be an obligation to draw on all forms of evidence to tell the most robust story possible. This means collaboration between all types of specialists and a major refocusing of resources on research projects that improve archeological understanding of all Arkansans—not just those who used written languages—over the course of millennia.