Juliet E. Morrow, ARAS-ASU Research Station

"Archeology is..." series - October 2025

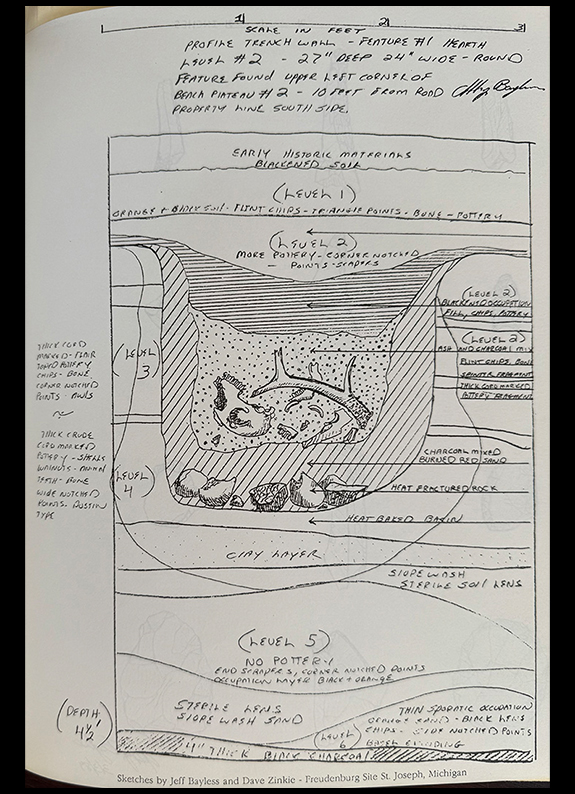

Soil is a very important and complex aspect of archeology. Pedology—more commonly known as the study of soil or soil science—is vital to interpreting stratigraphy (Figure 1). It is also essential to understanding the context of artifacts, plant and animal remains, and cultural features like house posts (Figure 2), burials and mounds, and discriminating between natural and cultural processes.

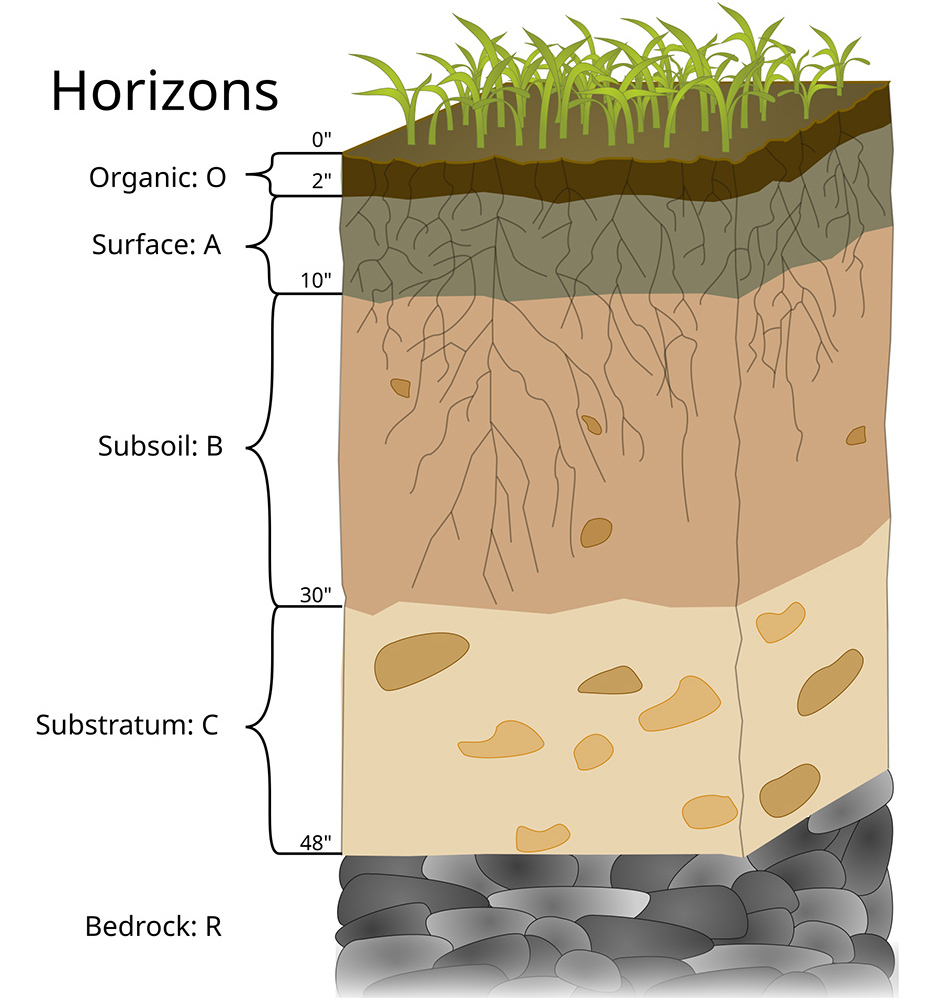

Soil horizons, not to be confused with archaeological strata, are layers formed by various natural biological, chemical, and physical processes. Wind, water and/or cosmic forces deposit material on the earth’s surface. As that parent material breaks down or weathers, and plants or crops grow on it, the soil becomes stable and forms an “A” horizon. The passage of time and the downward movement of clay particles from near the surface to a depth below (which varies depending on time, climate, slope, animal activity and addition of organic matter like leaves, pine needles, feces,etc.) create a “B” horizon (Figure 3). The typical profile in Arkansas is A-B-C.

A horizon is typically darker with decomposed organic matter and crumbly (friable). B horizon has more clay and can be very heavy (old) in consistency, and the C horizon is unweathered parent material.

When people live in one place for a while, their contributions to the soil can include a lot of animal and plant debris from meals and activities, such as making clothing, rope, containers, and tool handles. This organic rich soil created by human activity is called an anthrosol; literally it’s “man soil”.

Another aspect of soil in archeology is how it can be used to determine the provenance of artifacts and ecofacts (animal bones, plant remains and culturally associated materials that are not intentionally modified by people). Two good examples are pictured here (Figures 4 and 5). The fluorite bead in Figure 4 has soil residue on it and this could be traced to a provenance if further locational information was available. The end scraper in Figure 5 may not even be that old, and soil on it could help determine the minimum age of the artifact.

The significance of soil in archeology should never be underestimated, for every context in archeology must be understood through a study of the matrix within which the artifacts and ecofacts are supported. This is known today as geoarchaeology. This article has highlighted only two ways soils are vital to archaeology; there are many others.