By Kathleen Cande

Artifact of the Month - March 2019

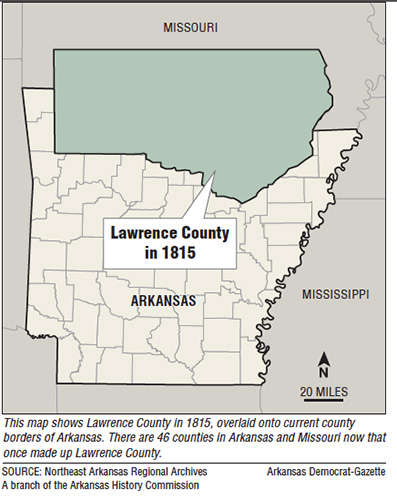

This month’s article is about a unique group of small artifacts found together in an archeological feature. From 2004 to 2009, the Arkansas Archeological Survey conducted excavations at the early nineteenth century county seat town of Davidsonville (Randolph County), Arkansas (Cande et al. 2008). The town served as the county seat for Lawrence County from 1815 to 1830. The town site became Davidsonville Historic State Park in the late 1950s.

One of the aims of our research at Davidsonville was to discover more about the buildings that made up the town, none of which had survived. Park staff also needed to know more about how people lived in the town to interpret it for the public. We also made use of newly available documents housed at the Northeast Arkansas Regional Archives (NEARA) in Powhatan, Arkansas.

Our excavations in 2004 and 2005 involved three buildings each in a different lot shown on the 1815–1816 town plat. One focus was the remains of a residence/tavern in Lot 35 just across the street from the brick courthouse. While excavating a wonderful cellar or trash pit feature in Lot 35 in 2004, Survey archeologist Jared Pebworth found what initially appeared to be a chunk of dirt (Figure 1). Upon further, careful examination, it was revealed to be part of a small leather pouch containing coins, straight pins, a copper button with shank, and a copper thimble. Figures 2 and 3 show the contents of the pouch before and after metal conservation.

It is appropriate that the pouch was found in Lot 35. Deed records indicate that Jacob Garrett owned the lot from 1819 to 1821 (Cande et al. 2008:165). He also had obtained a license to operate a tavern. During this time, taverns in the American South were part of private residences. People came to Davidsonville when the circuit court was in session, twice each year. They traveled from all over Lawrence County, which after 1815 was the northern third of Arkansas (Figure 4). These people needed places to stay while they were in court.

Other artifacts found in the cellar/trash pit feature include 76 whole or reconstructable ceramic vessels (bowls, a platter, plates, a soup plate, tea cups and saucers), glass bottles (beer and wine bottles), a brass candle holder, cutlery with engraved bone handles, sewing items including thimbles, needles and straight pins, and personal objects such as a glass pocket flask, gunflints, a musket ball, antler or bone dice, clay marbles, a jaw harp, a silver earbob, and glass beads.

The coins found in the leather pouch illustrate several things about currency in early nineteenth century America. There was no paper money at that time. Instead, silver coins were widely known to be relatively pure, and they held their value. Spanish coins were especially pure, and were used in the United States until just before the Civil War. Coins were minted in the United States beginning in 1792. Coins are dated, and their appearance offers clues to where they were minted and how they were used. All of the coins in the pouch were worn from being passed from person to person hundreds of times.

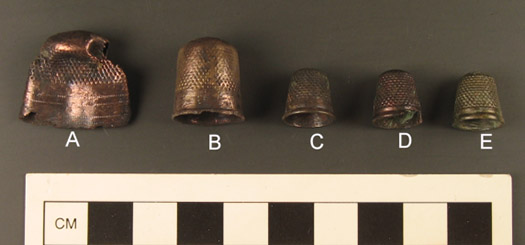

Figure 3. Selected contents of a small leather pouch after metal conservation: (clockwise from upper left) a. 1 bit cut from a Spanish 8 real coin (silver); b. Spanish Charles IV 8 real cut in half (silver); c. copper button with shank; d. US dime, 1798–1807 (silver); e. brass straight pin; f. cut quarter of a US 1808–1836 half dollar (silver); g. Spanish Charles III 2 real coin, 1776 (silver); h. Spanish 1 real coin cut in half (silver); i. perforated Spanish Charles IV 2 real portrait coin 1789 (silver); and j. a copper thimble.

There were five Spanish coins in the pouch, two whole and three cut. The smallest is a triangular piece cut from a whole coin. Even though a range of Spanish coins in different denominations were available, an accepted way to make change was to cut an eight real coin, for example, into a “piece of eight.” This piece and its fractional parts (½ and 1 real, 2 and 4 reales) were the principal coins of the Americas (Yeoman 1980:2). A piece of eight is shown at the upper left in Figure 3a. This one real or “bit” was worth 12½ cents. Beneath the piece of eight in Figure 3b is half of a King Charles IV portrait coin. Charles IV is shown on the reverse of this coin. The king’s name on the coin reads: CAROLUS IIII (Carolus was a medieval Latin form of the name Charles). Someone at the mint was trying to save money by adding a Roman numeral to Carolus III. It was easier to chisel an additional numeral rather than minting all new coins when Charles IV became king in 1788. Since it was cut in half, its value was 4 reales. A Charles III 2 real coin is below the straight pin in Figure 3g. It is dated 1776. This coin is worn very thin along the edge facing lower right in the photograph. Below this is half of a 1 real coin minted in Mexico City (Figure 3h). On the lower left in Figure 3i is a whole Charles III portrait coin issued in 1772. Marks on the coin indicate that it was also minted in Mexico City. This coin has a hole drilled in it. This is an indication that this coin may have been used as a charm by African-American slaves living at Davidsonville. Drilled Spanish coins have been found near slave cabins and in slave graves in Virginia and Texas (Davidson 2004; Lee 2011).

The two United States coins in the pouch are a half dollar cut capped bust coin cut to form a bit piece (Figure 3f). These coins were struck from 1807 through 1836. Beneath the half dollar and the straight pin is a whole draped bust heraldic eagle dime (Figure 3d). This coin is so worn that the inscriptions are not legible. All of these dimes were struck at the Philadelphia Mint.

In addition to the coins, five straight pins, a small copper thimble and a copper button were found in the leather pouch (Figure 3e single straight pin, 3j and 3c). The straight pins are of interest because of the way they were manufactured. All of the straight pins were examined using a microscope. This revealed that the heads are the brass wire type that were wrapped around a tin-plated brass shaft (Figure 5). The head usually consists of three turns anchored by means of a blow from a treadle-operated stamp that spread the top of the shank (Noël-Hume 1969:254). So although the manufacture of straight pins in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries was mechanized, it was a complicated effort involving different craftspersons for each of 18 distinct steps (Beaudry 2006:20).

The thimble found in the leather pouch is made of brass (Figure 6e). Thimbles manufactured in the eastern United States in the early nineteenth century were made in four sizes: girls’, maids’, women’s, and large (for men or women doing heavy sewing) (Beaudry 2006:105). The thimble in the pouch is definitely for a small girl since it is tiny. The plain copper button in the pouch was of a type commonly worn on men’s coats (White 2005:65).