Dr. Andrew R. Beaupré, Station Archeologist, ARAS-UAPB

Artifact of the Month - April 2020

The artifact of the month for April is a lead seal that was once attached to a bolt of cloth during the fur trade era. Lead seals have been referred to by a number of terms. They were once almost exclusively referred to as “wool seals” due to their association with fabrics (Noel Hume 2001:269). This term was deemed too limiting as the artifacts were also used to seal bundles or bales of general merchandise for transport. The term “bale seal” was then employed in the literature, but was abandoned for being similarly limiting (Stone 1974:281–297). The current literature refers to these artifacts simply as “lead seals.”

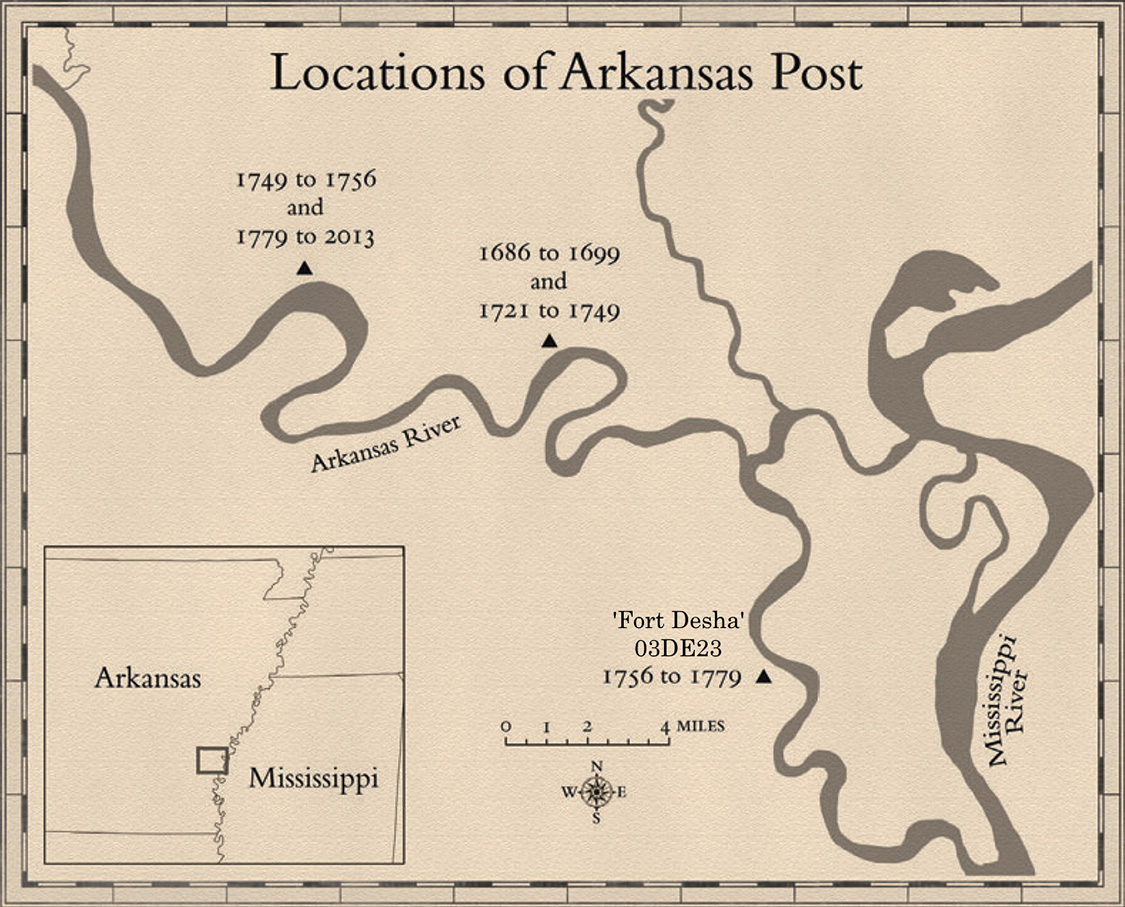

This lead seal was recovered from Fort Desha (3DE23), the Arkansas Post that was occupied from 1756 to 1779. This archeological site was first recorded by Edward Palmer during the Smithsonian survey of Native American mounds in the Arkansas River Valley. Palmer noted the existence of an old fortification “very probably built to protect a French Trading Post.” Palmer’s description of the site included a large hole which locals referred to as the powder magazine as well as mention of numerous trade goods recovered by relic hunters (Jeter 1990:240–241). This site has been referred to as Fort Desha, after Desha County, since its initial publication in 1894. The forests of the Delta reclaimed Fort Desha until it was rediscovered by a local avocational archeologist, Harvey McGhee, in the 1960s. McGhee heavily collected the site, donating several of his finds to local museums (Arnold 1984). The Arkansas Archeological Survey was informed of the site’s location in 1971. The lead seal pictured here remains in a private collection, but permission was given for it to be photographed by Survey archeologists in 1972. Limited archeological investigation was undertaken before a major flooding event significantly affected what remained of the site. The site is now believed to have been all but destroyed by the meandering of the Arkansas River. Due to the destruction of the site, photographs and artifacts donated to museums are all that remain of Fort Desha.

Lead seals were attached to bolts of fabric or bundles of general merchandise and are lumped into two general categories based on use. The seals either originated with a merchant sealing his goods until they reached their scheduled destination, or they were affixed by a government entity after the goods had been inspected and taxes had been paid (Noel Hume 2001:269). Each seal was marked with distinctive iconographic and alphanumeric symbols that indicate country of origin, type of goods, and/or quantity of cloth. When fabric reached its intended destination, the seals were often haphazardly discarded (Nassaney 2015:104).

This particular seal boasts markings on both the obverse and reverse (front and back) sides. The obverse is imprinted with a portion of the word “aunes" (written as avnes in period typography). The aune was an 18th century unit of length measure. In the French pre-revolutionary system, one aune was equal to two pieds (feet). The aune measurement was used by both the French and the English. From this information, we know that this seal was attached to a bolt of fabric that was 17½ aunes or approximately 33¼ modern feet in length. The reverse of the seal is marked with a series of letters "U/V(R?)IE". Given this format, it is likely French and probably indicative of the location where the fabric was manufactured (Personal Communication, Cathrine Davis). Unfortunately, given the poor quality of the reverse photo, no further information is available.

The recovery of a lead cloth seal at 3DE23 indicates the importation of fabric to the Arkansas Post. While no comprehensive study of fur trade documents relating to the American southeast exists, studies in the Great Lakes indicate that the single largest commodity in the trade was cloth (Anderson 1994). To an archeologist, this may seem counterintuitive, as cloth is very rarely present in the archeological record. Lead seals and other fabric related artifacts, such as buttons, thimbles, straight pins, needles, and scissors are indicative of the role cloth played in the 18th century frontier exchange economy and larger 18th century lifeways (Nassaney 2015:103–104).

***

Materials: Lead

Dimensions: Approximately 2.75 cm in diameter. Exact dimensions unknown.

Age Estimate: The class of artifact dates from the late 17th through the early 19th centuries. According to historical documents, the Fort Desha iteration of the Arkansas Post was occupied from 1756 through 1779.

Note: I would like to thank Cathrine Davis, MA, for her help with the lead seal research. Ms. Davis is a PhD student in Anthropology at the College of William and Mary.