Carl Drexler, ARAS-SAU Research Station

Artifact of the Month - June 2020

The June Artifact of the Month comes from Pea Ridge National Military Park, and is a piece of personal equipment that once belonged (probably) to a Federal soldier engaged in the decisive two-day battle that took place on 7–8 March 1862, often known as the “Gettysburg of the West.” The Arkansas Archeological Survey partnered with the National Park Service in a four-year Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Units (CESU) research program on different areas of the battlefield, using systematic metal detector surveys, geophysical surveys, archival document research, oral history, and excavation to better understand the landscape of the battlefield at the time and provide a foundation for improved interpretation at the park.

The Battle

The 3rd Illinois Cavalry formed in the late summer of 1861, drawing recruits, mostly farmers, from the central and southern parts of the state. They were sent to serve in the western theaters of the Civil War, and were part of Major General Samuel R. Curtis’s Army of the Southwest when it marched into northwest Arkansas in February of 1862. The 3rd Illinois was among the first troops hurried north from Little Sugar Creek on the morning of March 7, 1862, when Curtis realized that the combined Confederate and Missouri State Guard forces, led by Major General Earl Van Dorn, had successfully marched around his flank and were behind him, cutting his supply lines.

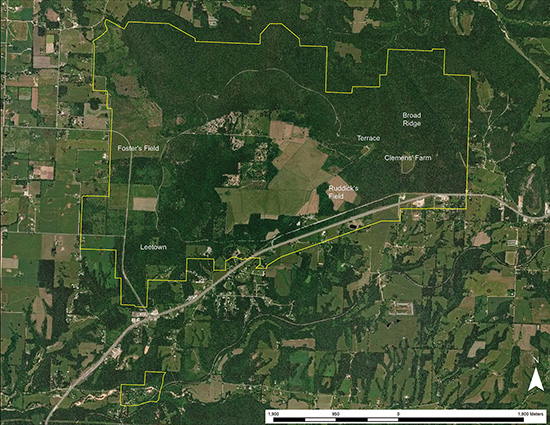

As Federal troops arrived at Elkhorn Tavern, which sat among open fields south of Cross Timber Hollow, they were hastily dispersed to meet pressure from the much larger Missouri State Guard force bearing down on them from the north. A portion of the 3rd Illinois went east with detachments from other units to help stop a move around the end of the U.S. line, while others were sent north of Elkhorn Tavern into an area known as “The Terrace.”

After establishing a fighting line in the Terrace, the lone battalion of the 3rd Illinois saw movement in the woods to the north, which developed into an approaching Missouri State Guard force. This was Brigadier General William Y. Slack’s brigade, men from the Hughes’s, Bevier’s, Rosser’s, and Riggins’s regiments and a much larger force than what the 3rd Illinois could effectively oppose. After offering short resistance, the 3rd Illinois retreated south under fire and received support from federal infantry that counterattacked, pushing the Missourians back and mortally wounding General Slack.

The Artifact

Why this long battle narrative to introduce the Artifact of the Month? Well, our installment for June is something we rarely see in the archeological record, as they were rarely seen on Civil War battlefields. It is a small, flat piece of brass, rounded on the edges and lobed when you look at its flat side. It is about an inch wide and three-quarters of an inch tall. It doesn’t look like much at first, but that’s because it’s part of a much larger piece of equipment.

This is a segment from a shoulder scale, a brass placard worn on the shoulders of U.S. uniforms at the time. Shoulder scales have an interesting history and purpose, as they are rooted in centuries of European military culture and reflect changing battlefield tactics. Going far back into recorded history, armies in Europe wore different kinds of armor to guard against the swords, arrows, and other weapons on the battlefield. By the 19th century, the widespread adoption and vast improvements in firearms technology had rendered most armor obsolete, and what remained was more ceremonial than functional. Shoulder scales bucked this trend.

The scales would be attached to a soldier’s coat by fasteners sewn into the jacket that held them onto the shoulders, covering the collarbones, shoulder blades, and adjoining muscles. While officially part of uniforms for infantry, cavalry, and artillery, only soldiers in the cavalry and artillery are believed to have worn them extensively in the field. This is because shoulder scales were designed to defend against saber strokes, not bullets. Who would be swinging sabers at cavalrymen and artillerymen? Other cavalrymen! At the time of the Civil War, battle tactics still held a place for cavalry-on-cavalry fighting, and some battles, such as the Battle of Brandy Station in 1863, pivoted on this kind of combat. Cavalry were also considered an effective force to overrun enemy artillery batteries, as their speed and maneuverability would hopefully allow them to close with the gunners before they could fire too many rounds.

If you were a cavalryman faced with potentially fighting an enemy cavalryman at close range, you had to be prepared to fight hand-to-hand. This meant drawing your M1860 Light Cavalry Saber (frequently called “the wristbreaker”) and slashing at your opponent. That overhand slashing motion carried the blade primarily to the neck and shoulders of your foe, meaning the shoulder scale could offer some small hope of protection.

If you were an artilleryman, standing on the ground watching a troop of enemy cavalry come thundering in your direction, you were just as concerned about those swords (provided you survived the pistol bullets). Again, those swords were being swung at you overhand, and your head and shoulders would be most vulnerable. Again, the shoulder scale would offer some protection, or at least hope for it.

This piece of shoulder scale from the Terrace area of Pea Ridge battlefield was likely associated with a cavalry or artillery unit that fought there; only the 3rd Illinois Cavalry fits the bill. It’s a great find and an uncommon luxury to be able to offer up such a tight association. It also tells us something about the way in which the 3rd Illinois was equipped and what they looked like in the field. Wearing shoulder scales in battle is not a given, so evidence they were worn at Pea Ridge tells us this piece of equipment was both issued and worn by the troopers. It also suggests the men were wearing short “shell” jackets, which would have been trimmed in yellow (the branch color for cavalry). Some cavalry units, later in the war, are depicted wearing a five-button “sack coat,” a rather shapeless jacket worn extensively by the U.S. infantry during the war. It is very rare to see depictions of shoulder scales on sack coats, but shoulder scales worn with shell jackets were quite common.

This artifact also opens a connection to the individual soldier who wore it, and leads us to ask many questions about him. Where is the rest of the scale? Why was it left in the field? Was the soldier who wore it wounded, perhaps in the neck or shoulder, breaking the scale? Was it lost in the confusion of moving through the forest on the Terrace? Finding pieces of personal equipment always brings us closer to the people in the past. This would have been something that the man wore on his clothing daily for months, and its loss would not have been a casual thing. Finding it by chance during a metal detector survey in 2018, being able to understand its connection to the landscape of the battle and to the other artifacts associated with those two days, and our ability to describe all this to you displays the power of Conflict Archeology to link us to our ancestors, and open a window onto their experiences.

Further Reading

-

Civil War Archeology: Investigating the Battles at Wilson's Creek & Pea Ridge

-

Pea Ridge & Civil War Archeology

-

Archeology at Ruddick’s Field at Pea Ridge National Military Park

-

2018 Training Program at Pea Ridge Battlefield

-

The Civil War Picket - Where cannon roared: Pea Ridge excavation yields a trove of artillery, other artifacts