Juliet E. Morrow, Sarah D. Stuckey, and Brandy Dacus

ARAS-ASU (Jonesboro) Research Station

“It is time to correct past mistakes in point typology.” (Perino 1986:119)

“Not all point types have been recognized or named.” (Perino 1985:xv)

“Just what is a point type? First, it is a group of distinctive, similar (in manufacture, appearance, and function) tools believed to have been made and used during a certain period and over a limited area. That is, a point type is thought to represent something made by a particular society, or several adjacent ones, and used during part of their histories. Secondly, a point type is a classification and communication aid constructed by archeologists. There is no way to prove that the types we recognize have anything to do with the ways past societies perceived or classified their projectiles [emphasis added]. … It is only because archeological analyses repeatedly provide evidence that a point type occurs over a limited area for a restricted period that archeologists suspect they have a relationship to particular groups.” (Wyckoff and Jackman 1988:113)

The Arkansas Fluted Point Survey (Morrow and Dacus 2017) has helped us to produce the Arkansas Paleoindian Database (APD). The database includes both fluted and non-fluted Paleoindian point types. The intent of this article is to improve fluted point terminology and the APD, and to define a new point type for the Central Mississippi Valley (CMV), a geo-cultural ecosystem encompassing portions of Arkansas, Missouri, Illinois, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Mississippi as defined by Morse and Morse (1983:2, Figure 1.2). In recording points for the Arkansas Fluted Point Survey (Morrow and Dacus 2017), we found a number of points that had never been typed. There were also fluted points in the Arkansas Archeological Survey’s (ARAS) collections that had been typed as “Sedgwick.” Among the points typed as “Sedgwick” there were examples that resembled Gainey, Clovis, and Folsom points. There were others that didn’t resemble any of these types. Since at least 1993, the type name Sedgwick has been used by a number of researchers across the country, including the first author (Morrow 2006), but the type was never formally defined. The Sedgwick type was informally defined as a smaller, more triangular fluted point type (Morse and Morse 1983:Figure 3.7e-h). Recently, Jack Ray (2012) applied the name Sedgwick to a group of points from Missouri but did not provide measurements in his article. At least some of those points are now typed as Gainey (Morrow 2015).

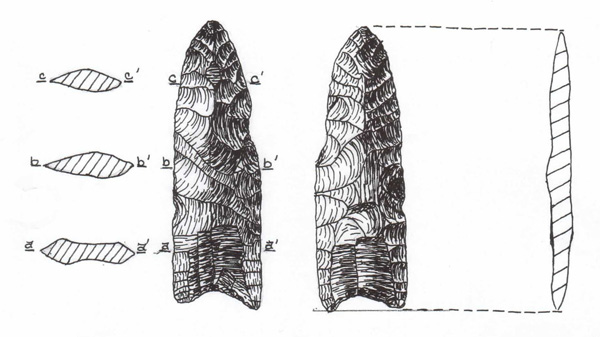

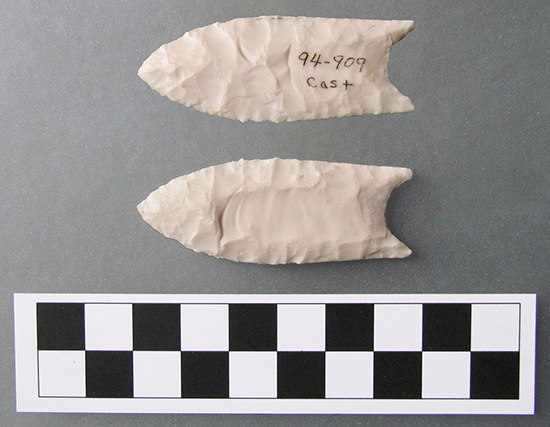

Using the name Sedgwick for a fluted point type is problematic because there was not consistency in how the type name was applied in the past. Figure 1 is an illustration of one of the fluted points illustrated by the Morses (1983) and typed as a “Sedgwick”. This point is a Gainey as typed by Morrow in 2009 for a draft manuscript on Ozarks Fluted Points on file at the ARAS-ASU Research Station. Figure 2 is a photograph of a resin cast illustrated in the Morse and Morse volume that is also typed as a Sedgwick. The resin cast in the Survey’s collection is slightly similar to the Barnes type (see Ellis 1984; Morrow 1996; Wright and Roosa 1966) in outline shape, and slightly similar to the Folsom type in flute thickness; however, metric attributes, uniqueness, and the lack of context suggest that the point from which this cast was made may be a modern replica. Juliet Morrow documented a similar point from Illinois and another from Iowa; both turned out to be modern replicas. When asked their opinion about the point in Figure 2, several modern flintknappers told us that it has attributes suggesting to them that it could be modern. Due to the lack of context, we have opted not to include it in the APD. If we are going to use the term Sedgwick, then it should be formally defined and based on fluted points that are derived from secure archeological contexts. We have a number of small fluted points in the Survey’s collections and from private collections, some of which were initially typed as Sedgwick (Figure 3). We are formally defining these as “Points Formerly Typed as Sedgwick” or PFTAS.

PFTAS: A New Point Type

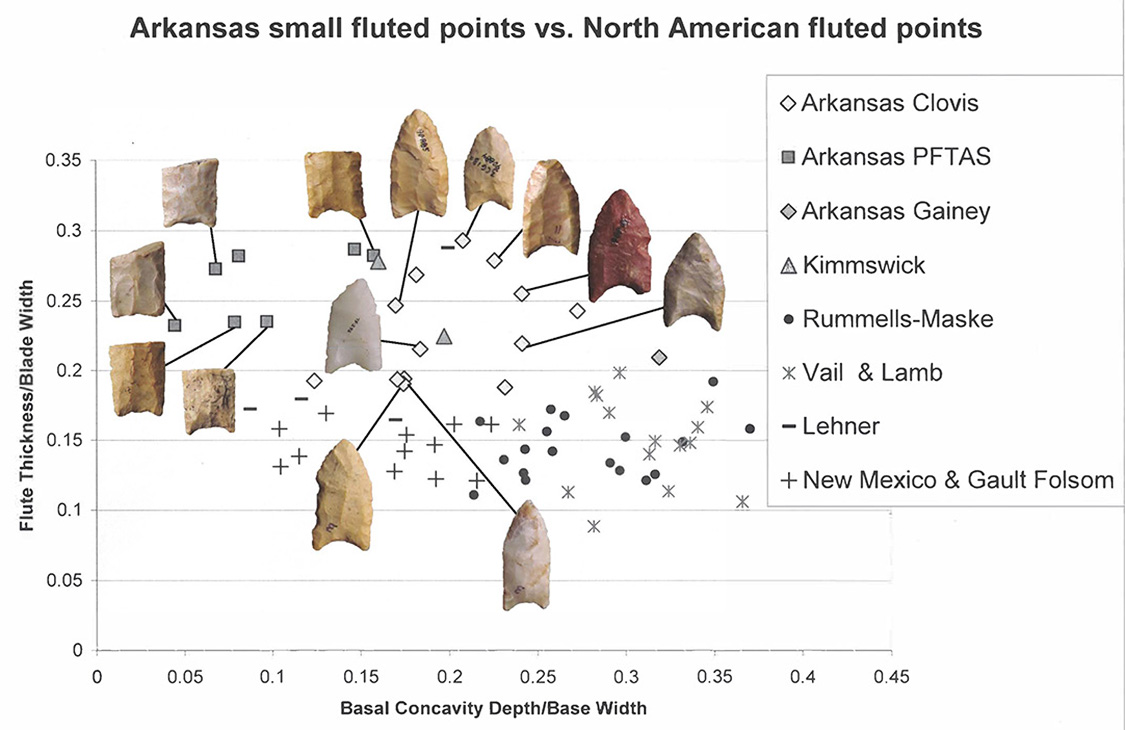

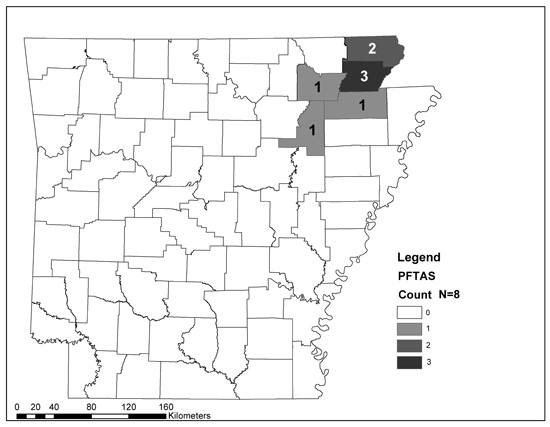

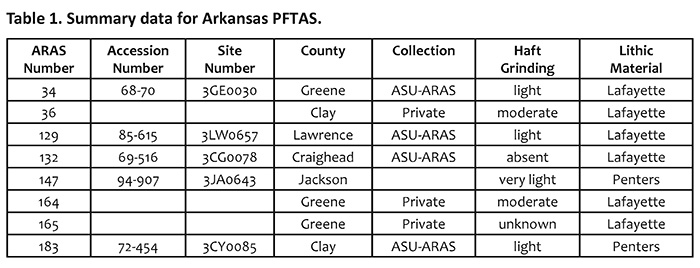

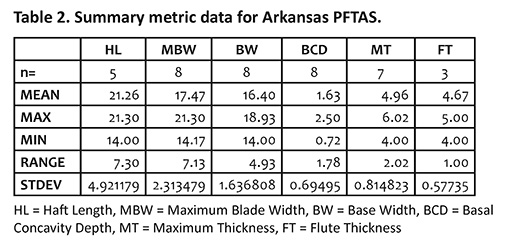

As of today, there are eight PFTAS identified in the APD (see Figure 3, Table 1). Five are in the Survey’s collections and three are from two different private collections. Metric data are summarized in Table 2. There are no complete PFTAS; all eight specimens are proximal or haft fragments with a shallow or no basal concavity. Most of the PFTAS have two or more small narrow flake detachments on at least one face that produced a flake scar ridge that remains on the point and a slight projection near the center of the base. PFTAS have a plano-convex cross-section and/or some have remnant patches of the original surface of the flake they were made from. Lateral and basal margin grinding is light to moderate when present. Haft grinding and the breakage patterns suggest they are not preforms but finished points. Use-wear analysis has not been conducted. To better understand the untyped small fluted points in the APD, metric data from a sample of Folsom points from the state of New Mexico and the Gault site in Texas available in the Paleoindian Database of the Americas (PIDBA); four small Clovis points from the Lehner site in Arizona; Clovis points from Kimmswick (a mastodon kill in Missouri); and Gainey points from the Vail site in Maine, Lamb site in New York, and the Rummells-Maske site in Iowa were compared. In 2005, the senior author typed ARAS No. 129 as a Gainey preform (Morrow 2006); however, reanalysis types it as a PFTAS.

PFTAS form a relatively cohesive group. As seen in Figure 4, PFTAS tend to be thinner and have a shallower basal concavity than points typed as Clovis. Clovis points occupy the central portion of the scatter plot in Figure 4. Compared to Gainey, Clovis points are slightly more variable, but overall they are thicker and with a slightly shallower basal concavity. They do not appear to be miniature Clovis, Gainey, or Folsom points. There is a continuous size distribution from PFTAS to large Clovis, Pelican, and Gainey points. For comparison, the “miniature” fluted points reported by Ellis (1994:256) range from 22.4 to 27.0 mm in total length (n = 2), 12.0 to 13.5 mm in width (n = 4), and 2.2 to 2.8 mm in thickness (n = 6). Two untyped “miniature fluted points” from the Pavo Real site in Texas are pictured online; they are not similar in shape or in technological attributes. The current distribution of PFTAS is the Western Lowlands of northeast Arkansas (Figure 5), but it is possible that they occur throughout the Mississippi Delta, particularly in the vicinity of the Lafayette Formation, e.g., southeast Missouri, southern Illinois, and northwestern Mississippi.