Ann M. Early

In the spring of 1539, Hernando de Soto and his expedition landed in Florida to begin a four-year quest for valuable booty and vulnerable Indian societies that could be turned into laborers and Christians. Soto lost his wealth and finally his life in the disastrous outcome, but there were two momentous consequences: Europeans learned about Native people of southeastern North America through expedition reports and survivors’ tales; and Native people were forever changed by warfare, disease, and subsequent environmental crises, shaping new societies that often broke with older cultural traditions and with the archeological signature of their ancestors.

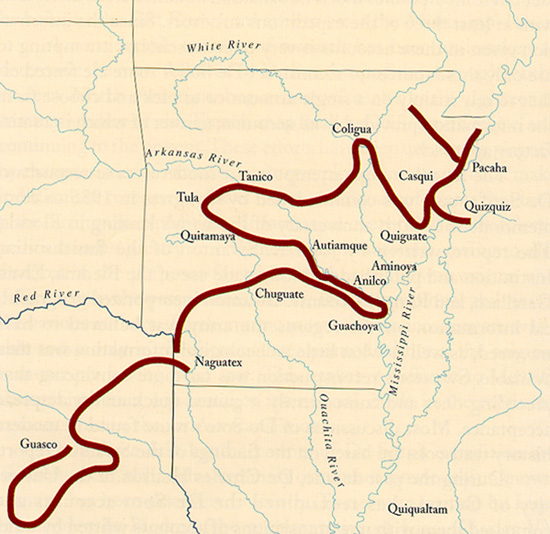

Four hundred years after the Soto expedition, historians, archeologists, and politicians undertook an ambitious re-telling of the event that culminated in a weighty report, published in 1939, laying out the likely route and events along the way. Archeologists hoped to use this report to guide them in linking historic Indian tribes to the mounds, artifacts, and other archeological remains of their pre-contact ancestors. Politicians and historians hoped to mark the expedition’s path on the landscape with markers, statues, newly named landscape features, and with amenities to attract tourists and enhance local histories.

Arkansas lacked archeologists and any organized understanding of the age and distribution of archeological sites, but amateur historians enthusiastically joined the project to identify and mark the expedition’s trek through the state. The 1939 route became incorporated into local and state history and local landscapes over the next two decades.

But as time went on, archeologists increased their understanding of Native sites and improved their ability to estimate the age and cultural connections of Native people across the Southeast, and they began raising questions about the 1939 study. Still, when the Arkansas Archeological Survey installed the first large group of trained archeologists in Arkansas in 1969, the age and distribution of de Soto era settlements across the state were largely unknown. Sites highlighted in the 1939 study were likewise poorly known.

A high priority for the Survey in its first decade was to systematically document sites across the state, and to improve understanding of their age and cultural connections. Aided by advances in analytical methods, dating techniques, and accumulated scholarly knowledge in journals, books, and other reports that were spreading in professional meetings, Arkansas archeologists reevaluated sites highlighted in the 1939 report. Like their colleagues in other states, they found widespread mistakes in proposed age and cultural identity.