Kathy Cande and Jared Pebworth

As part of a cooperative agreement with the National Park Service (NPS), Southwest Region, the Arkansas Archeological Survey (ARAS) assessed the condition of historical metal artifacts collected during the 1950s–1970s from Arkansas Post National Memorial. This cooperative agreement was part of a larger effort by the NPS to inventory and catalog archeological collections curated with the Survey. In 1992, funding was provided to construct an electrolysis tank in the ARAS Sponsored Research Program laboratory.

Why is conservation of metal artifacts necessary? The majority of metal artifacts in the Arkansas Post collections are iron. When in contact with the air or buried (in contact with moisture), iron artifacts begin to corrode or rust. Rust is iron oxide. If nothing is done to stop the process, eventually the iron will completely convert to rust and disintegrate. Other metals form corrosion products as well, such as the greenish-blue coloration that develops on copper objects. This corrosion product, however, protects the metal it covers. Copper and brass artifacts are cleaned by hand. Once they are conserved, metal artifacts will remain in relatively stable condition. As with any artifact conservation technique, electrolysis is reversible.

Jim Barnes, laboratory supervisor at the time, spent a week at the Bureau of Archaeological Research at the University of Florida for training in setting up and using electrolysis for conservation of iron artifacts. Current ARAS metal conservator, Jared Pebworth, received training in metal conservation from Arkansas State Parks Historic Resources & Museum Services.

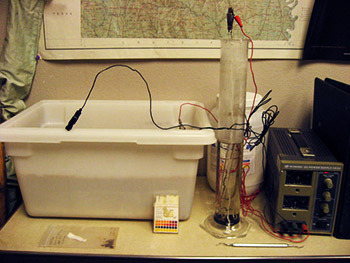

Electrolysis (or electrolytic reduction) is a process by which direct current is passed through an ionic substance that is dissolved in a suitable solvent, producing chemical reactions at electrodes and separation of materials. In other words, it converts corrosion products (i.e. rust) to a more stable or easily removed form. Electrolysis tanks were set up at ARAS, using a heavy plastic tub and a smaller tube for single items (Figure 1). A power source provides 3 amps of electricity in deionized water with a sodium hydroxide electrolytic medium. Artifacts are prepared for reduction manually, monitored during the electrolysis process, and dried. Once the full stabilization process is completed, the iron artifacts are coated with tannic acid and then sealed using polyurethane to prevent renewed corrosion (Memory 2002). Finally, the artifacts are returned to their original storage containers. Figure 2 illustrates some of the instruments used in metal conservation.

A set of 244 iron artifacts from Arkansas Post was selected for conservation. These include armaments and accessories, tools, hardware, and wagon parts. Non-ferrous (“ferrous” means containing iron) metal objects in the collection include artifacts made of copper, brass, and pewter. Artifacts such as cutlery with iron tines and wooden handles are not appropriate for electrolysis because they are made from two different materials. Only a representative sample of iron nails were conserved because there are hundreds in the collection. All artifacts selected for conservation were photographed before any work began. An electrolysis record form was created to record catalog numbers, a brief description of the artifact, beginning and ending treatment dates and any additional observations. A black and white photograph of the artifact before conservation was also attached to this sheet. This illustrates the typical documentation process we use.

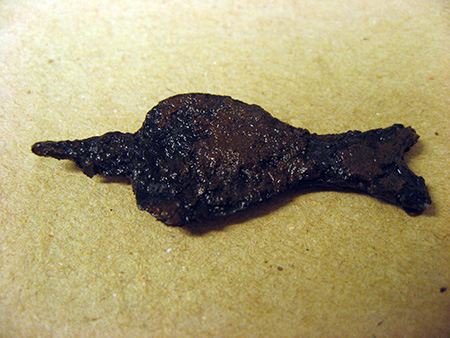

Metal conservation also helps us identify the function of heavily corroded artifacts. Figures 3–6 illustrate a series of steps that an artifact (or group of artifacts) goes through during conservation. The artifact in this series is a piece of gun hardware, probably part of an iron trigger guard. This process may take weeks, months, or even years. The artifact in Figures 3–6 is from the seventeenth-century protohistoric Grigsby site in northeast Arkansas.

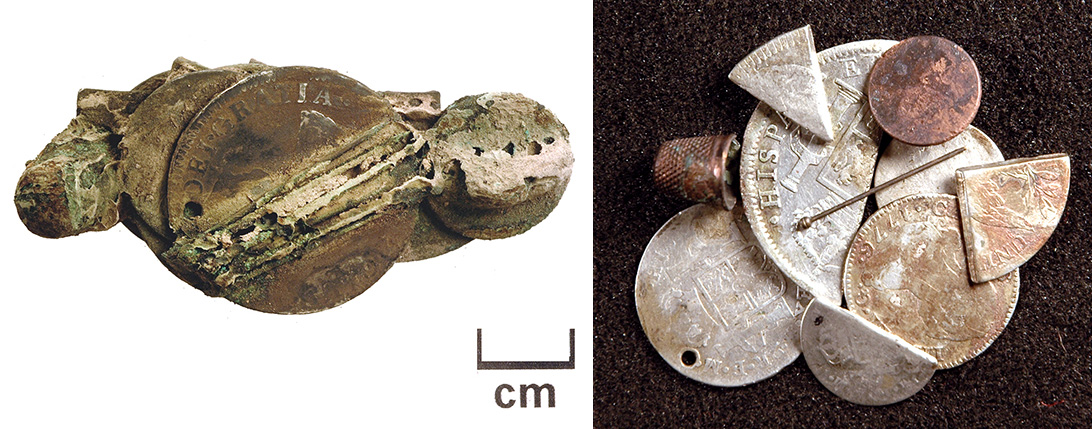

A curious artifact was found during excavations at Davidsonville Historic State Park in Pocahontas, Arkansas (Figures 7–9). Davidsonville was the first county seat town in Arkansas, and dates from 1815–1830. The artifact, shown in Figure 7 just after excavation was found in a cellar or trash pit beneath a tavern. After cleaning it was found to be a small leather pouch containing coins, a thimble, and several straight pins, encrusted with copper corrosion. The straight pins were handmade, with each brass head applied by hand.

Many fragments of artillery shells were found in recent excavations at Prairie Grove Battlefield State Park, including the pieces shown in Figure 10. Metal conservator Jared Pebworth was able to fit the shell back together (Figure 11). Personal objects were found in excavations at Camp Monticello, a World War II Italian prisoner-of-war camp in southeast Arkansas (Figure 12). After electrolysis they are easily identifiable buttons (Figure 13).

Reference Cited

Memory, Melissa

2002 Appendix E, Arkansas Archeological Survey Basic Procedures for Metal Conservation. In Summary Report on Arkansas Post National Memorial (3AR47) Archeological and Related Archival Collections and Automated National Catalog System (ANCS) Data Reintegration, by Kathleen H. Cande, Arkansas Archeological Survey, Final Report, Project 01-04. Submitted to Ms. Carolyn Wallingford, Curator, Great Plains System Support Office, Omaha, Nebraska.