Juliet E. Morrow (ASU Research Station), Randel T. Cox (University of Memphis), Jami J. Lockhart (Computer Services Program) and Sarah Stuckey (ASU Research Station)

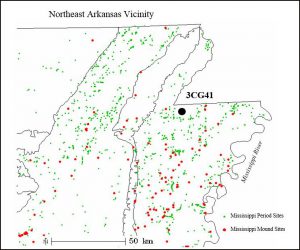

The ASU Research Station has been investigating the Old Town Ridge site since 2008. The site is located in Craighead County, Arkansas on a relict stream channel of the St. Francis River system. The site is widely recognized as an important Native American Mississippi period habitation and ceremonial site since the early 1900s was formally recorded in 1967 by local avocational archeologist R.W. (Dub) Lyerly, Jr. The site consists of multiple houses and numerous ceramic and lithic artifacts have been collected from the surface and from unauthorized digging, including a ceremonial mace discovered in 1925 that is now curated at the Gilcrease Institute and a marine shell gorget displaying elements reminiscent of Braden and Craig-style iconography rendered by Native American artists during the Early and Middle Mississippi period. The iconographic images of narratives and characters link communities from geographically-distant sites together, the larger of these sites include the civic-ceremonial centers of Cahokia in Illinois, Etowah in Georgia, and Moundville in Alabama, and the ritual mound center known as Spiro in eastern Oklahoma.

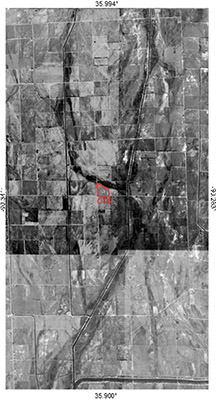

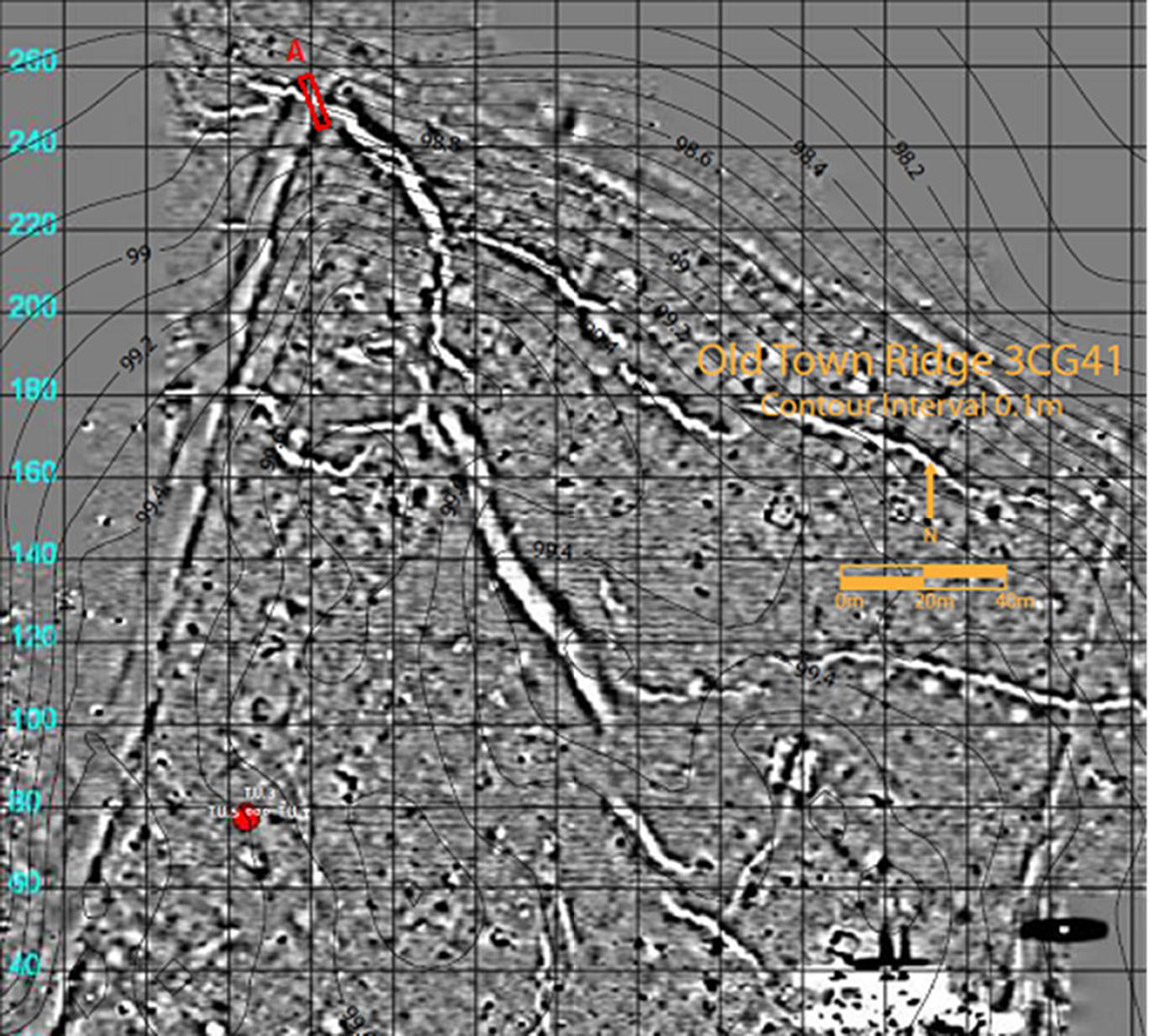

Our investigation began when aerial photographs that Russell Henry brought to Juliet Morrow were examined for potential site boundaries and interior features. The objectives of the project were to first conduct gradiometry over the entire 18-19 acre village. For comparison, Old Town Ridge is as large or perhaps a little larger than the Parkin site. Centimeter-level spatial precision was achieved by establishing a permanent grid system using a total station transit. Between 2008 and 2010 the fortified site was surveyed using a fluxgate gradiometer to identify and locate structures and other archeological features for use in ongoing research examining intrasite organization and Native American life ways during the Mississippian era (A.D. 700-1541) in the region. Results indicate a fortification ditch, palisade, numerous structures (large and small, burned and unburned), and earthquake features from the New Madrid earthquake or earlier seismic events. Results from the gradiometer survey can also be used to search for areas of the site that have been less disturbed (Lockhart et al. 2011).

The 2008-2010 study focused on documentation of the Middle Mississippian village which included gradiometry and limited testing which was published by Morrow and colleagues.

One radiocarbon date obtained on hickory nutshell from a central hearth inside a small square (4 x 4 meter) house suggests the village was last occupied between circa A.D. 1290 and 1420. Anomalies that represent liquefaction features are visible in the gradiometry image of the village suggest that the occupants may have abandoned the village due to the circa 1450 earthquake paleoseismologists (geologists who study earthquakes) have recorded in the New Madrid Seismic Zone (NMSZ).

If you look closely, the above gradiometry image shows liquefaction features that crosscut other anomalies that may represent cultural features including the possible palisade/ditch, posts and house walls, burials, hearths, and pits. Some anomalies may be the result of vandalism, uncontrolled excavation, animal burrowing, and other activities. Since 2008, Morrow has observed large badger dens across the entire site. Animal burrows and past uncontrolled excavations may mimic prehistoric features. Recently our research has focused not directly on the anomalies that appear to be cultural features per se, but instead on the natural features that most likely represent past earthquake events called paleoseismic features (sandblows, grabens, dikes and sills) and their relationship to cultural features, particularly the ditch/palisade.

In 2017 Morrow teamed up with Randel Cox to conduct research at the site to answer three questions , 1.) Are there paleoliquefaction features at Old Town Ridge site?, if so, then 2.) how many seismic events generated liquefaction features at the site and what is the age of each liquefaction event? 3.) How do these ages relate to large historic and/or prehistoric earthquakes identified elsewhere in the Mississippi River Valley?

Answering these questions helps refine the recurrence interval of strong ground shaking in the region and the potential for strong earthquakes to have influenced the movements and activities of human groups in the past. Artifact collections from Old Town Ridge and regional research strongly suggest that people abandoned the site sometime around A.D. 1400. Factors that may have influenced the abandonment of the site and numerous other Middle Mississippi period sites in the New Madrid Seismic Zone (NMSZ) include but are not limited to climate change, earthquake activity, and warfare.

Artifacts dating to the Late Woodland/Early Mississippi period indicate earlier communities at Old Town Ridge. Episodic occupation may have enlarged the village from the Late Woodland period to the Middle Mississippi period. Potential enlargement of the village and expansion of the apparent palisade wall and/or ditch during the Middle Mississippi period is probably influenced by population increase, warfare, climatic changes and possibly even earthquake activity. Establishing a chronology of earthquake activity at Old Town Ridge is an important first step toward future investigations of the Native American communities that lived at the site from as early as 11,000 B.C. to circa A.D. 1400.

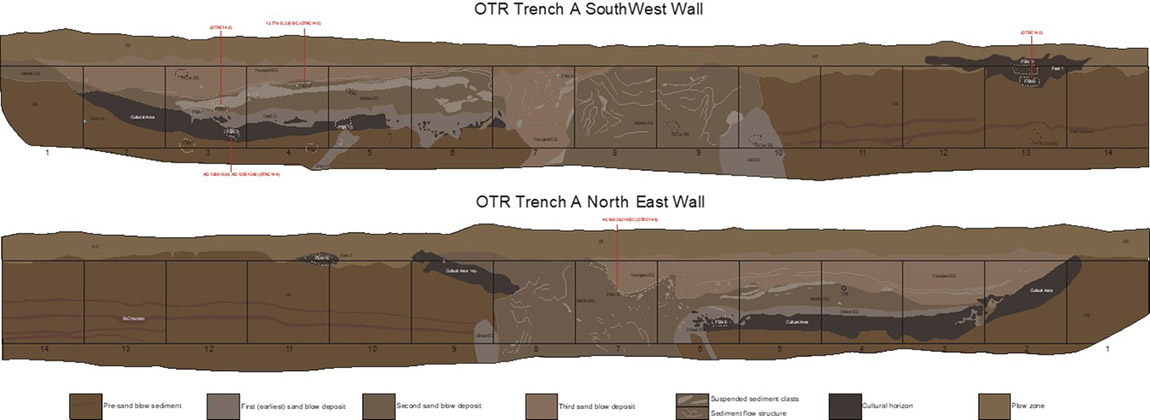

We selected a location for a trench at Old Town Ridge to cross a gradiometry anomaly suggestive of a large sand dike where it crossed an anomaly suggestive of a cultural feature (see topo/gradiometry map). Excavation of a 14 m-long trench (Trench A) did indeed reveal a large (3 meter-wide) compound sand dike crossing a cultural horizon. Trench A exposed four sediment deposits (FIGURE), a cultural deposit, and a plow zone. The sediment deposits include a pre-liquefaction alluvial deposit and three separate sand dikes and associated sand blows. The cultural deposit post-dates the alluvium and pre-dates the sand dikes. Sand venting caused vertical displacement of the cultural horizon across the vent zone.

The margins of the sand dike vents and the base of the sand blows are erosionally scoured by rapid flow of liquefied sediment. The full width of the first sand dike cannot be measured due to subsequent dike intrusion along the same vent. The preserved parts of the first sand dike (SW trench wall, meter 4.8 to 5.3 and 9.7 to 10.5; NE wall, meter 6.4 and 8.9 to 9.2) are associated with a sand blow overlying the cultural horizon (SW wall, meter 3.2 to 7.3; NE wall, meter 3.2 to 6.7), and it contains clasts of the cultural horizon and the alluvium substrate. The second sand blow vent (SW wall, meter 7.9 to 9.7; NE wall, meter 6.8 to 8.9) is associated with a sand blow extending from meter 1.0 to 7.1 on the SW wall and meter 2.1 to 6.8 on the NE wall. The second vent and blow contain sediment flow structures and clasts of alluvial substrate and of the first blow. The third vent (SW wall 7.0 to 8.0) is associated with a sand blow extending from meter 1.4 to 6.5 on the SW wall and meter 1.9 to 7.8 on the NE wall. The third vent and blow contain sediment flows structures and clasts of alluvial substrate and of the second blow.

The first dike and blow have a firmer consistency, have a darker Munsell value and have no sediment flow structures preserved, consistent with the first dike and blow being significantly older that the two later blows. The cultural horizon below the first blow yielded a radiocarbon age of AD 1280-1320, AD 1350-1390 (OTRC14-4), consistent with the first dike and blow being related to the strong circa AD 1450 earthquake within the NMSZ as described and discussed by Martitia Tuttle and colleagues as magnitude 7.6 or greater earthquakes. The second and third dikes and blows have similar softer consistency, lighter Munsell values, and preservation of sediment flow structures, and we interpret them to have formed relatively recently and in rapid succession. In the absence of geochronologic age data to constrain the timing of the second and third dikes and blows, we use these observations to interpret them to be related to two of the three strongest New Madrid earthquakes of 1811 and 1812. According to Munson and colleagues (1977) dike width is related to earthquake magnitude, and the second sand dike is the widest. Thus, we suggest that the second dike was formed during the 12/16/1811 New Madrid earthquake because it is estimated to have been the strongest event of the sequence and the closest to Old Town Ridge according to Arch Johnston who published this inference in 1996. The third was probably the next closest strong earthquake of the sequence on 2/7/1812.

We can now answer the three questions set forth in our research design: 1.) Are there paleoliquefaction features at Old Town Ridge site? The answer is a definite yes, there are minimally three paleoliquefaction features. 2.) How many seismic events generated liquefaction features at the site and what is the age of each liquefaction event? There are a minimum of three, possibly four paleoliquefaction events and the uppermost two (possibly three) represent the 1811-1812 event; one is most likely the circa A.D. 1450 event. 3.) How do these ages relate to large historic and/or prehistoric earthquakes identified elsewhere in the Mississippi River Valley? The paleoliquefaction events we interpret at Old Town Ridge are well known and have been previously studied by numerous paleoseismologists. Our working hypothesis is that the A.D. 1450 seismic event was the likely cause of site abandonment at Old Town Ridge. We interpret the rectangular line surrounding the village as a trash-filled moat. No posts or postmolds were observed in the 14 m trench.Future work at the site will examine other cultural and natural features that may confirm our findings thus far and also answer the following questions: 1.) Did Native Americans build a wall or palisade at the site, if so, when?

Acknowledgements and References:

Thanks to Dr. Thomas J. Green, Shaun McGaha, Russell Henry, volunteers and members of the Arkansas Archeological Society and all of the owners and stewards of the site for helping us learn so much about one of the great sites of northeast Arkansas.

Arch C. Johnston and E. S. Schweig,

1996. The enigma of the New Madrid earthquakes of 1811-1812. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 24, pp.339-384.

J. Lockhart, Juliet E. Morrow, and Shaun McGaha

201 A Town at the Crossroads: Site-Wide Gradiometry Surveying and Mapping at Old Town Ridge Site (3Cg41) in Northeastern Arkansas. Southeastern Archaeology 30(1):51-63.

Juliet E. Morrow, Robert Taylor, Jami Lockhart, and Shaun McGaha.

2013 Old Town Ridge (3CG41): A Fortified Village in the Land of Milk and Honey. Arkansas Archeologist 51:1-24.

Patrick J. Munson, S. F. Obermeier, Cheryl A. Munson, and Edwin. R. Hajic

1997 Liquefaction evidence for Holocene and latest Pleistocene seismicity in the southern halves of Indiana and Illinois: A preliminary overview. Seismological Research Letters 68, 521–536.

Martitia P. Tuttle, E. S. Schweig, J. D. Sims, R. H. Lafferty, L. W. Wolf, and M. L. Haynes

2002 The earthquake potential of the New Madrid seismic zone. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 92, 2,080–2,089.

* * *

Originally posted May 8, 2017

Revised on January 26, 2023