Jeffrey Mitchem, Parkin Research Station

When the expedition of Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto crossed the Mississippi River in the summer of 1541, he and the hundreds of people accompanying him entered what is now Arkansas. They spent the next year roaming through the state until Soto’s death in 1542. The surviving group decided to abandon the expedition and head to Mexico, which they did after many tribulations.

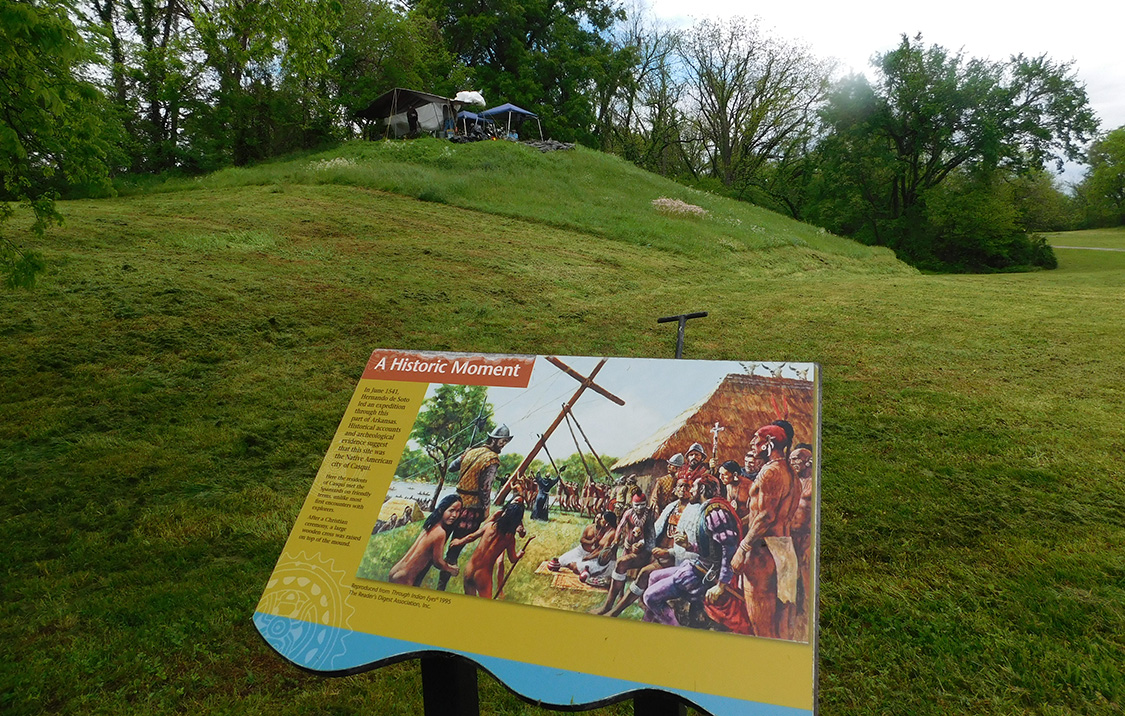

Shortly after crossing the Mississippi, they heard of a powerful chief named Casqui, who ruled over a number of settlements in some of the river valleys. Soto traveled to Casqui’s village, where he was welcomed with gifts and hospitality. He remained there a few days, and one of the things he did was to have a wooden cross constructed and raised atop the mound that was the platform for the chief’s house. Some Catholic priests among the expedition members conducted a Mass, and the cross was apparently left in place by the residents of Casqui’s village.

Since the 1960s, several artifacts have been found at the Parkin site that came from the Soto expedition. Based on these objects and the location and configuration of the settlement, many archeologists believe that the Parkin site is the location of Casqui’s village. Limited excavations atop the mound at Parkin in 1966 encountered part of a large wooden post that had been burned in place. After some samples were taken, its location was mapped, it was covered with a sheet of white plastic, and then it was covered back up. In the 1990s, some analyses were performed on the wood samples, finding that the post was of bald cypress and dated between 1515 and 1663. These tantalizing results whetted the appetites of the archeologists and staff at Parkin Archeological State Park, who dreamt of digging down to this post to see if a tree ring date would show that it was cut in 1541. If so, this would be strong evidence that the Parkin site is probably Casqui.

Through the aid of Mark Michel of The Archaeological Conservancy, this dream finally came true in April, 2016. Mark directed Dr. Jeffrey M. Mitchem to a private foundation, the Elfrieda Frank Foundation, who awarded a grant to cover the costs of such a project. A small team of highly skilled archeologists from the Arkansas Archeological Survey were brought together, and Arkansas State Parks provided Rangers to guard the site from disturbance at night. The excavations went quickly, and the post remnant was located, along with the 50-year-old remains of the plastic sheet that had covered it. The post appeared to have been set in a place where another post had stood before, possibly immediately before. The earlier post had been burned in place, then a hole was dug down for setting the new post/possible cross. The project attracted a fair amount of media attention.

The charred wooden post remnant and its soil matrix were carefully excavated and meticulously documented. The best preserved portion was removed intact, wrapped securely, and driven across the state to the University of Arkansas campus, where Dr. David W. Stahle, Professor of Geosciences and a leading expert in tree-ring studies, examined it, but unfortunately it was too broken and incomplete to derive a tree-ring date.