Dr. Juliet Morrow, ASU Research Station

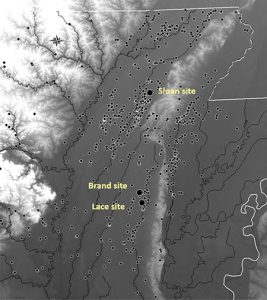

The Sloan Dalton cemetery site is the oldest known formal open-air cemetery in the New World. It is located on a late Ice Age sand dune in Greene County, Arkansas between Crowley’s Ridge and the Ozarks in a physiographic region known as the Western Lowlands. Arkansas State University student Mary Ann Sloan told Dr. Dan Morse (then the Research Station archeologist for the Arkansas Archeological Survey in Jonesboro) about the site and it was eventually excavated in order to preserve information that was being lost to vandalism. The 1974 excavations revealed clues that people of the Dalton culture, between about 12,480 and 11,300 calendar years ago, buried their dead in ceremonial fashion. At that time, much of northeast Arkansas, including the Western Lowlands, was covered in deciduous vegetation and contained a wide diversity of animal and plant resources.

The Dalton culture is recognized as a distinctive suite of stone tools that occur at archeological sites across the Eastern Woodlands. Included in this suite of tools are bifacially flaked lanceolate “Dalton points” that functioned as cutting tools as well as spear tips, awls/perforators, and end scrapers, and bifacially flaked adzes for wood chopping and hide processing. Several types of formal unifacially retouched flake tools often accompany these formal bifacial tools. The flaked stone technology of the Dalton people is extremely refined and is on a par with that of contemporary Paleoindian cultures to the west such as Folsom, Midland, and Plainview. Tools made from chert and other toolstone types are the most commonly available evidence for understanding Dalton lifeways. Items made from organic materials like wood, leather, and plant fibers are rarely, if ever, preserved in open air sites like the Sloan site. Despite the lack of organic remains, the Sloan site provides an unprecedented window into ceremonial activities of hunter-gatherers during the Pleistocene to Holocene transition.

The Sloan site excavation covered an area of about 12 meters by 12 meters. As artifacts were exposed in the large block-style excavation, they were gently cleaned with bamboo picks and paintbrushes. Many artifacts occurred in clusters or concentrations. The discovery locations of all Dalton artifacts were piece-plotted on a grid and catalogued in the field. Many artifacts were also photographed in the field in the locations where they were excavated. Artifacts and bone fragments were shallowly buried in sandy sediment. Bone preservation was very poor; only tiny fragments from 114 catalogued locations were recovered. Spatial patterning of the artifacts and bone fragments suggests there may have been about 28 to 30 people buried there.

Most of the known tools of the Dalton tool kit in northeast Arkansas come from the Sloan site. Microscopic analysis indicates that many tools recovered from Sloan do not appear to have been made specifically for ceremonial use. Many would have been functional tools for conducting subsistence related activities such as cutting and scraping plant foods and wood; scraping and perforating hides to make clothing and footwear; incising bone and antler and wood; chopping and scraping wood for spears, tool handles, shelters, and canoes; cracking nuts; crushing pigment; manufacturing chert tools; etc. Projectile points can also serve as a material expression of group identity, so Dalton points and Sloan bifaces embody symbolism beyond their functionality.