John R. Samuelsen, Jerry E. Hilliard, Kathleen H. Cande, and Jami J. Lockhart

When the Arkansas Archeological Survey (ARAS) was created by Act 39 of 1967, one of the main responsibilities of the organization was to house all records pertaining to archeological sites in the State of Arkansas. This information is vital, not only to archeological researchers, but also to federal agencies, state agencies, and contractors who need it to make sure they are accounting for the state’s cultural resources when conducting projects. While paper forms contained this information, the Arkansas Archeological Survey created a statewide archeological site database called Automated Management of Archeological Site Data in Arkansas (AMASDA) to ensure site information was accessible and properly maintained. But with over 48,000 sites and counting, searching through paper forms would make this process unnecessarily difficult and time-consuming.

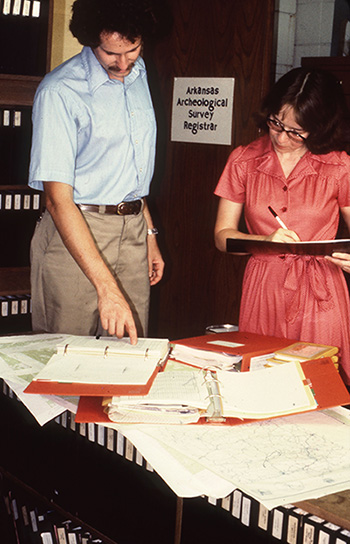

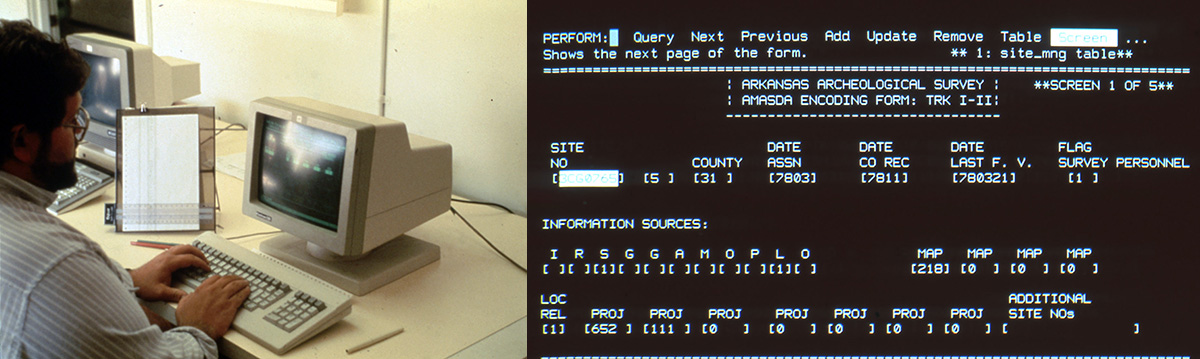

The creation of AMASDA in 1979 was a pioneering effort in digital storage and retrieval of archeological information. Paper site forms were created to match the database so that data could be easily entered based on the site documentation. The entered information could then be searched using a computer to retrieve the required information (Hilliard and Riggs 1986). While this is a basic skill today, it was an innovative effort for statewide organizations at the time. This effort, which actually began as early as 1977, was heavily supported by the Survey’s administration and involved many meetings regarding what data should be included in such a system. Cathy Moore-Jansen, then ARAS Registrar, and Peer Moore-Jansen (who largely spearheaded the project) worked tirelessly to come up with a suitable site data recording form. AMASDA started as a site database, but new types of information have been added as technology allows for more complex and larger datasets to be linked together. For example, it now includes a projects database containing important information on archeological projects executed across the state. Stored information includes the digitized project location, who conducted the project, and what information was uncovered about archeological resources.

The AMASDA system has been recognized as being one of the oldest (but still active) archeological databases in the country. Most importantly, it is still maintained and upgraded with each new release of technology, ensuring the archeological record is not lost.

“…only the Arkansas Archaeological Survey’s AMASDA system continues as a robust and operational system that has migrated its data repeatedly from earlier software architectures and platforms to its current and greatly expanded one—all the while maintaining data integrity.” – Limp (2011:275)

One major upgrade to AMASDA began in 2007 with the creation of AMASDA Online, a web interface which allows for internet access to the system through a web browser. This is available to qualified professional archeologists working for organizations with a need to know. This upgrade was possible due to a grant from the Arkansas Highway and Transportation Department (AHTD). The information in the database is critical for organizations to conduct projects and comply with Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (as amended). The ability to easily access, search, and retrieve relevant archeological data means that projects being executed by the AHTD, other agencies, or businesses can proceed efficiently while still evaluating the impact on the state’s cultural resources. This also has the benefit of allowing archeological researchers, such as archeological faculty and students at universities, to be able to conduct their research.

Continual development of AMASDA Online has expanded the datasets available. It now has all original paper site files available for download. An online Geographical Information System (GIS) provides a spatially oriented interface to retrieve the information. Most project reports are available as the ARAS Registrar’s Office continues to digitize this information. Other types of information include a list of citations for important archeological reports and resources, a radiocarbon date database, and extended site file information. A study units database contains information on archeological study units (time periods, cultural phases, etc.) described in A State Plan for the Conservation of Archeological Resources in Arkansas (Davis 1982).

Since this information is critical not only to the cultural resources of the state, but also to federal/state agencies and businesses, it is archived and backed up through a system of servers in multiple locations. This system ensures that the work put into digitizing all this information over several decades is not lost even in the case of a tornado or fire. Archeological databases contain important information about our past, but this knowledge can only be preserved if the databases are constantly protected, maintained, and upgraded.

References

Davis, Hester A.

1982 A State Plan for the Conservation of Archeological Resources in Arkansas. Arkansas Archeological Survey Research Series No. 21, Fayetteville.

Hilliard, Jerry E. and John Riggs

1986 AMASDA Site Encoding Manual: Version 2.0. Arkansas Archeological Survey Technical Paper No. 1. Arkansas Archeological Survey, Fayetteville.

Limp, W. Fredrick

2011 Web 2.0 and beyond, or on the Web Nobody Knows You’re an Archaeologist. In Archaeology 2.0: New Approaches to Communication and Collaboration, edited by Eric C. Kansa, Sarah Whitcher Kansa, and Ethan Watrall, pp. 265–280. Costen Digital Archaeology 1. Costen Institute of Archaeology Press at UCLA.