During the height of its looting in the winter of 1935, the Spiro site—located in northeastern Oklahoma just 10 miles west of Fort Smith—was catapulted to fame by a headline published in the Kansas City Star (December 15, 1935) proclaiming it “A ‘King Tut’ Tomb in the Arkansas Valley …” Today, the Spiro Mounds Archaeological Center is known throughout the world as a pre-Columbian Native American ceremonial site where the largest collection of sacred objects on the continent was deposited in a single location. A significant number of those items, acquired by University of Arkansas zoology professor and Museum curator Samuel C. Dellinger as the looting was taking place, is now housed at the University of Arkansas Collections Facility in the Arkansas Archeological Survey’s Coordinating Office.

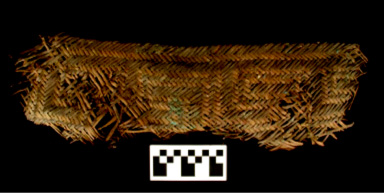

For decades, this extraordinary assemblage of ornaments and art objects crafted of bone, copper, marine shell, stone, and wood, in addition to woven basketry and fabrics, was attributed to a variety of phenomena, including burial ceremonialism, performance of religious rites, political display, and far-flung trade and exchange networks. While these factors provide at least partial explanations, the long-term studies of James A. Brown (Emeritus Professor of Anthropology, Northwestern University) suggest that much of the material unearthed from a special feature preserved within the Craig Mound at Spiro—the so-called Hollow Chamber—reflects the performance of a single elaborate ceremony, which took place during a time of protracted environmental and social stress. This ceremony was orchestrated by resident Spiroans but attended by people from many neighboring communities.

These new interpretations, supplemented by years of subsequent research at Spiro and at contemporaneous residential and ceremonial centers distributed across eastern Oklahoma, northwest Arkansas, and southwest Missouri, have kindled renewed interest in conducting further investigations using some of the latest technologies available to modern archeology.

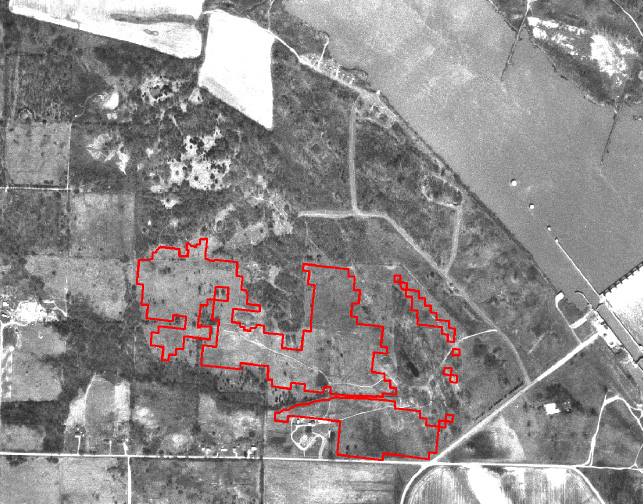

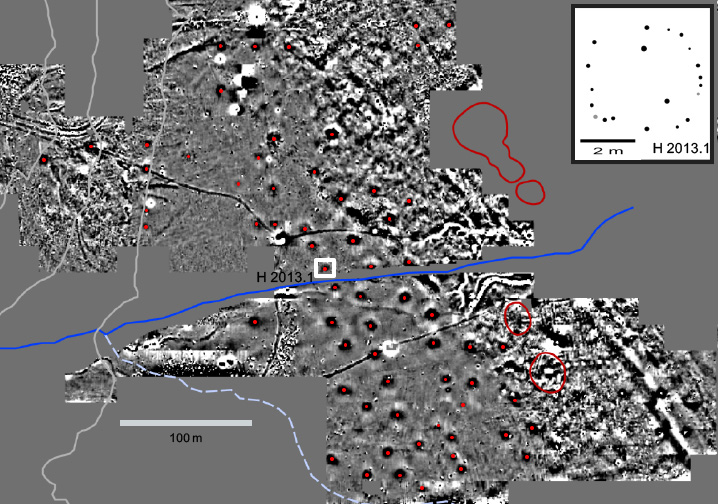

Beginning in 2011, a research team comprised of several individuals from the Oklahoma and Arkansas Archaeological Surveys has initiated a new, long-term investigation called the Spiro Landscape Archeological Project. We are using geophysical prospecting technologies (gradiometry, electrical resistance, electrical conductivity, magnetic susceptibility, and ground penetrating radar) to identify previously unknown archeological features, and we are conducting limited excavations to acquire additional information about those features and their contents. Collaborating with us are staff from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Dennis Peterson of the Spiro Mound Archaeological Center, and members of the Caddo Nation and Wichita and Affiliated Tribes.

To date, we have covered the entire site area within the boundaries of the Archaeological Center (which is managed by the Oklahoma Historical Society) with gradiometry, and completed additional examination of selected features using the other technologies. We have identified several new features and we have acquired more accurate information on the original shape and orientation of some of the key mounds at the site. One of our most interesting discoveries so far is a large series of magnetic anomalies (approximately 60), arranged in a pattern of relatively orderly rows adjacent to the Craig Mound. Excavation of four of these features verifies that they are structures—most likely hastily erected shelters occupied for a very short time, leaving relatively few artifacts. Compounding our puzzlement concerning their use is the fact that none of the excavated structures has a preserved hearth. Pending further investigation, we are unable to link the age or use of these structures with other events at the site, but a working hypothesis is that they were built and occupied by visitors who gathered to participate in the dramatic ceremonies that produced the fabled treasures so carefully arranged within the Hollow Chamber later entombed by the Craig Mound.