Tim Mulvihill, UAFS Research Station

Dr. Jami Lockhart, Computer Services Program

Feature of the Month - February 2022

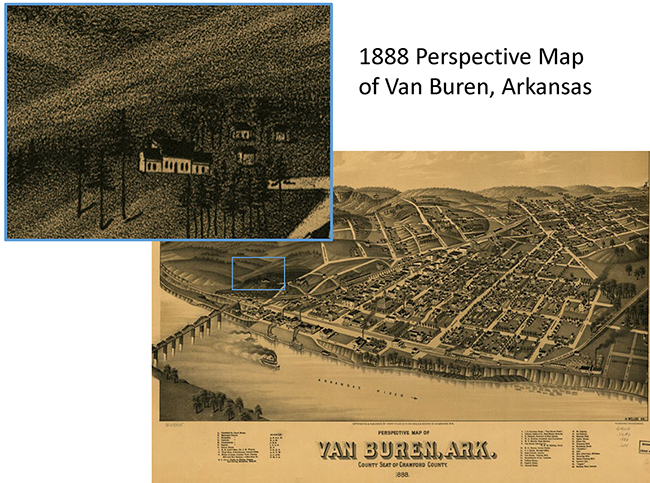

The Drennen-Scott Historic Site, located in Van Buren, Arkansas, is the antebellum home of John Drennen, one of the founders of the town. The house began as a one-room structure built in 1838, with additional rooms added soon thereafter. Nineteenth century homes in Arkansas often included a detached kitchen and smokehouse somewhere on the property, but there was no record or living memory of these structures on the Drennen-Scott property. An 1888 perspective map of the town showed some outbuildings to the northeast of the house and possibly something behind the house (Figure 1).

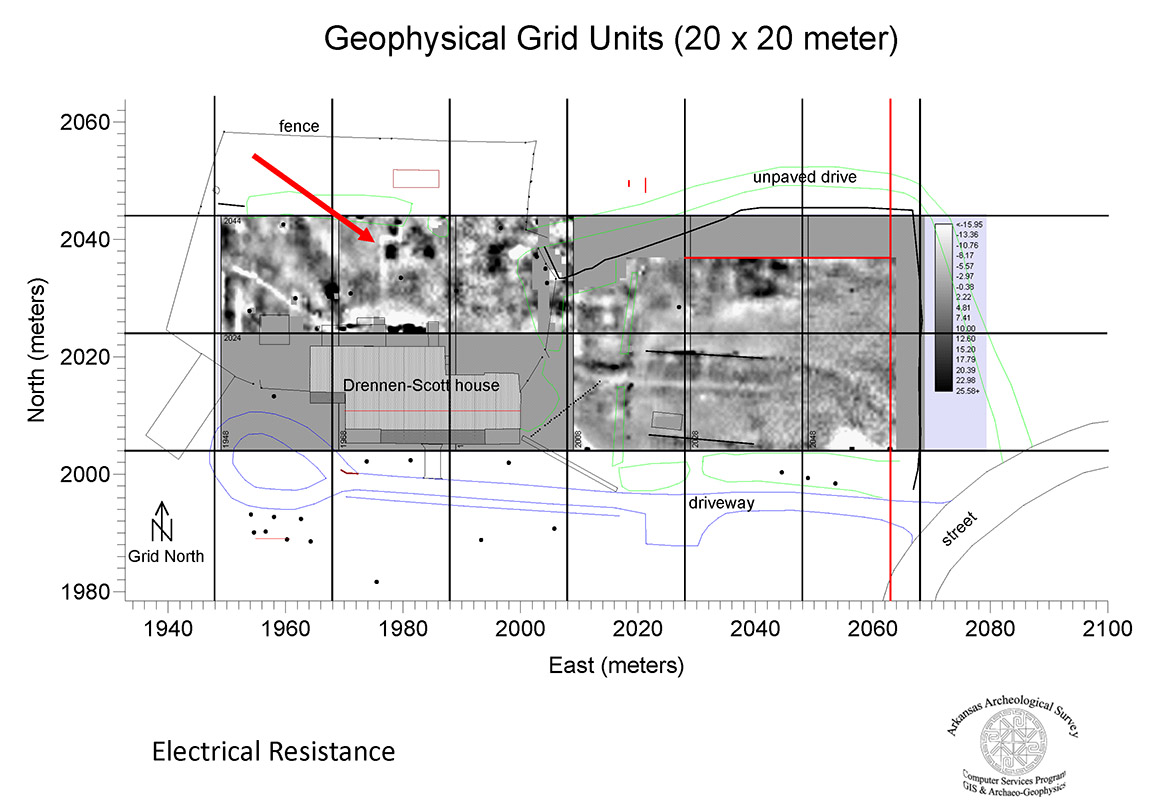

When the University of Arkansas - Fort Smith (UAFS) acquired the property in 2005 to rehabilitate it into a museum and teaching laboratory for their Historic Interpretation degree program, they asked the Arkansas Archeological Survey to assist with conducting archeological research on the property. Tim Mulvihill, Station Archeologist at UAFS, led the work, which began with a geophysical survey conducted by Dr. Jami Lockhart and assisted by Survey personnel including Jared Pebworth and Mike Evans, and Arkansas Archeological Society (AAS) volunteers. The goal was to identify locations of former outbuildings or other features. One of the technologies used was electrical resistivity, which sends a weak electrical current into the ground to measure resistance. The physical properties of archaeological features commonly differ from the surrounding natural soil matrix, resulting in measurable differential resistance to the flow of electricity. For example, the moist fill of a buried ditch might provide a less resistant pathway for electrical current than the surrounding dry and compacted natural soil matrix. This technology did identify several anomalies on the property, including a rectangular area of high resistance in the backyard (Figure 2).

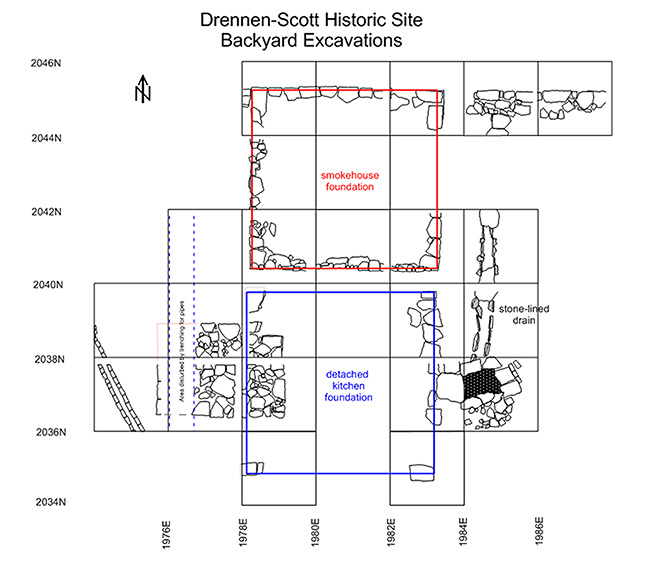

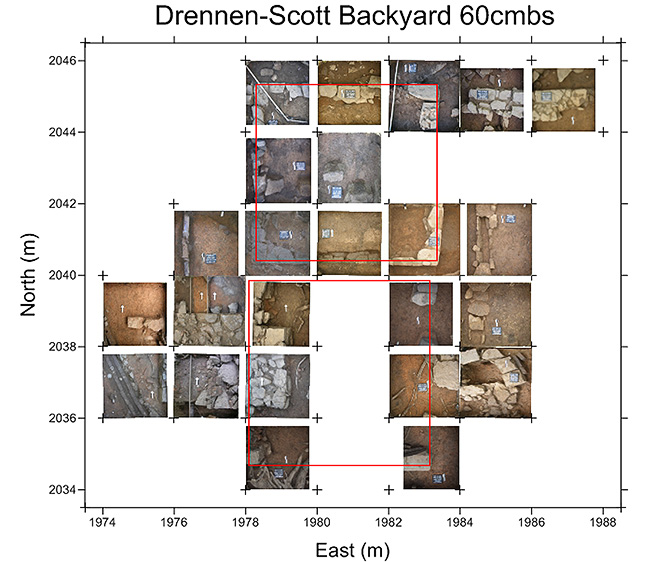

Initial excavations conducted by Mulvihill and AAS volunteers uncovered a large (3.2m x 2.4m), stone foundation just below the surface, which was possibly the foundation for the brick chimney associated with the detached kitchen (Figure 3). Further excavations over the years with UAFS Introduction to Archeology students, AAS members, and other Survey personnel proved this was the case, eventually finding the four stacked-stone corner piers of the detached kitchen (Figure 4) and, just behind it, the continuous stone foundation for a smokehouse that was of similar size – both being 16 by 16.5 feet (or 4.87m x 5.04m) (Figure 5). The smokehouse was identified by the thick layer of ash inside the foundation, which contained among other things animal bones and occasional lead shot (Figure 6). Artifacts found around the kitchen footprint included animal bones, broken ceramics, buttons and other fasteners, glass bottle fragments, pipe fragments, and other typical debris. These two outbuildings were built on a sloping hillside. Once the structures were no longer in use (a new kitchen was attached to the main house circa 1890s), later occupants of the property moved soil to bury the foundations, creating a more level backyard, and accidentally preserving the foundations (Figure 7). These buried deposits provide a time capsule of life in the nineteenth century on an urban farmstead in Arkansas.