Mary Beth Trubitt

Arkansas Archeological Survey-Henderson State University Research Station

March 2025

During the nineteenth century, stoneware pottery was manufactured in several regions of Arkansas, producing jars, churns, and crockery for local customers (Bennett and Worthen 2021; Smith 1972; Starr 2003). One important stoneware production center was in Dallas County. Potters working near Princeton and Tulip between the 1840s and the 1890s included the Bird brothers, John C. Welch, Nathaniel Culberson, and Elisha A. Nunn.

Investigating historic pottery industries requires the skills of both archeologists and historians. Archeology can provide information about the facilities and techniques used in production and their spatial distribution across the landscape, and about the products themselves and their use by consumers. Archival sources and oral history can tell us the identities of the potters and plant owners, when they were operating, details on how the production was organized, and how the products were advertised and marketed.

There are four pottery kiln sites in Dallas County listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The National Register is this country’s listing of places deemed worthy of preservation in recognition of their historical significance. Beverly Watkins (1982) researched and recorded these pottery kilns as archeological sites while working for the Arkansas Archeological Survey in the 1970s.

The earliest of the Dallas County potteries was the Bird Kiln north of Tulip. Brothers Joseph, Nathaniel, William, and James Bird (or Byrd) came to Arkansas from North Carolina, and by 1843, Joseph and Nathaniel were operating a stoneware pottery. The Bird Churn, now in the Henderson State University Archives, is stamped “J.&.N.BIRD” and “8” on the shoulder and neck and signed “Manufactured by Joseph and Nathaniel Bird in the State of Arkansas, Clark County, May 1843” on the base (Figure 1). This would be the first stoneware made in Dallas County (which was not created until 1845) and some of the earliest in the state. A scatter of salt-glazed sherds and bricks are all that remain on the surface at the Bird Kiln, recorded as archeological site 3DA12.

By 1850, Nathaniel and William Bird were working at the pottery. Soon after, William Bird moved his operation to a new location near Princeton. This pottery prospered, and he took on apprentices. In 1860, he sold the pottery to one of his apprentices, John C. Welch (this is the Welch Pottery Works, 3DA9). William Bird left the area during the Civil War but returned, and was operating a third pottery near Tulip by 1867 (3DA542). He sold that pottery to Harry F. Samuels in the mid-1880s, and moved to Texas.

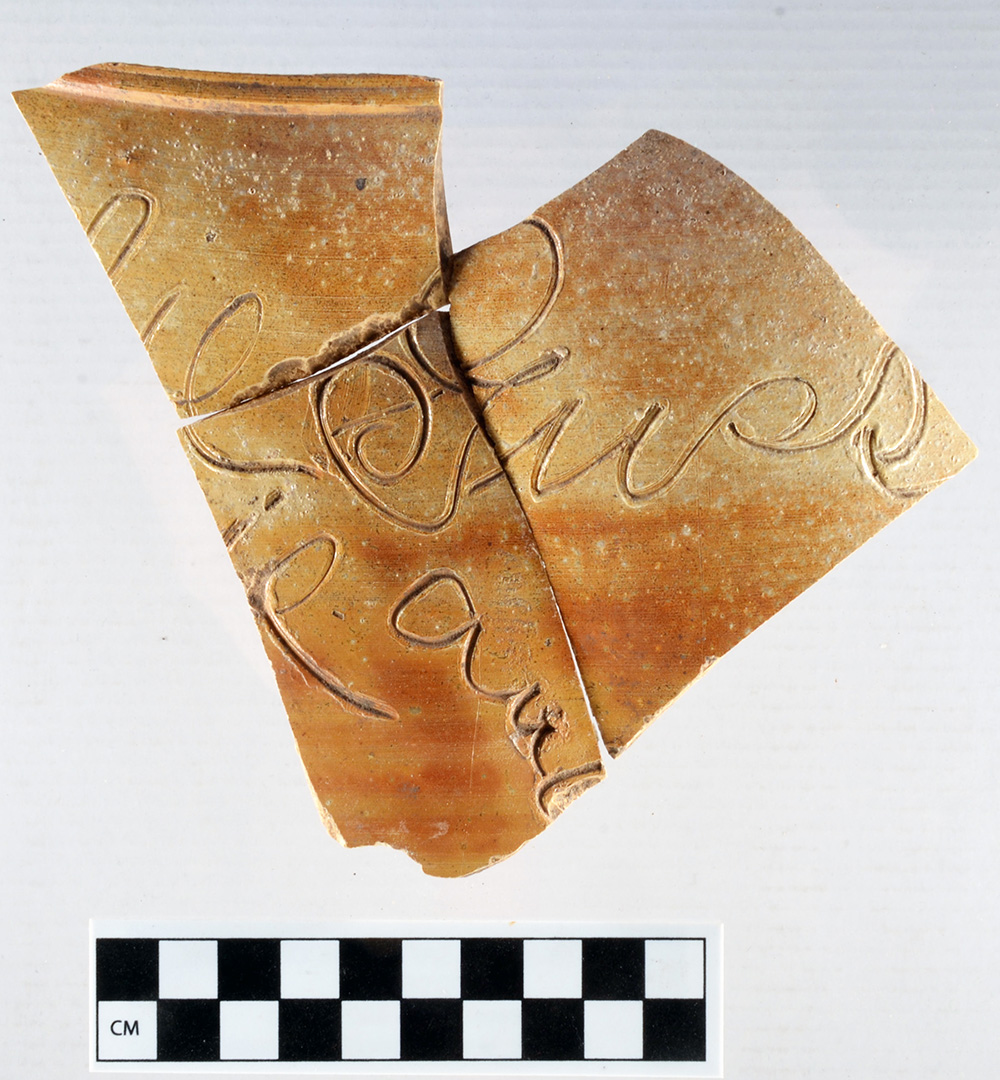

John Welch operated Welch Pottery Works from 1860 until about 1891. Recording the site as 3DA9, Beverly Watkins recorded pottery “wasters” – sherds that had been discarded by the potter – as well as bricks from an old house foundation. Sherds curated at the Arkansas Archeological Survey’s HSU Research Station include several sherds stamped with the letter “W” (for Welch) and number “2” (for volume) (Figure 2). After 1891, Welch moved to his son’s house and rebuilt his kiln at a new location (Wommack Kiln, 3DA8) (Figure 3). There, he continued making pottery until his death in 1909 or 1910. This was the best preserved example of a “groundhog” style kiln in Dallas County when recorded as an archeological site in the 1970s (Greer 1977; Watkins 1982) (Figure 4).

Several other potteries operated in Dallas County, albeit for shorter periods of time. Nathaniel J. Culberson (or Culbertson) is listed as a potter on the 1860 census. The Culbertson Kiln has been recorded as archeological site 3DA21. He left Dallas County during the Civil War and by 1880 was operating a pottery in Tennessee. Elisha A. Nunn operated a pottery kiln in Dallas County (3DA540) before establishing a pottery in Hot Spring County in the mid-1870s. That pottery was purchased in 1892 by Oliver C. Atchison, who began manufacturing bricks at a plant that later became the Acme Brick Company. Since Nunn had operated a pottery in Dallas County and Atchison had been a potter in Saline County, the Hot Spring County brick industry was the offspring of both these local traditions. Lafayette Glass either learned to make pottery from John Welch or from Oliver Harris, an African American man he enslaved prior to the Civil War. Glass set up a pottery in Dallas County (3DA543) and operated it for about a year before moving to Saline County. By 1870, Glass had established a pottery in Benton, and Harris was working there as well.

By 1890, the only Dallas County pottery in operation was run by John Welch. Larger pottery centers had developed in railroad towns like Benton in Saline County during the final decades of the 1800s (Buchner 2015; Trubitt 2004). By the beginning of the twentieth century, wider availability of glass canning jars and metal kitchenwares meant the collapse of the Benton stoneware industry. The potteries that survived – such as Niloak Pottery in Saline County, Camark Pottery in Ouachita County, and Dryden Potteries in Garland County – specialized in art pottery. The brick industry in Hot Spring County continues to this day.

Examples of jugs and crocks from the Bird and Welch potteries can be viewed at the Dallas County Museum in Fordyce, Arkansas.