Jami J. Lockhart, PhD, Arkansas Archeological Survey

"Archeology is..." series - April 2024

Geophysics is a natural science that studies physical processes and properties of the earth. The prefix “geo” is defined as relating to the earth, and “physics” describes relationships between matter and energy. In this brief description, we will also add “archaeo” to “geophysics” because we are using geophysical methods to study human history and prehistory.

Consider past civilizations that have dug in the soil (trenches, moats, irrigation channels, wells, storage pits, graves…), piled the soil (mounds, floors, defensive embankments, paths…), and constructed houses (wood, cane, clay, stones, bricks, fire hearths…). Measurable traces of these historic actions and materials remain in the soil. Even simple day-to-day living activities, such as food preparation and waste disposal, can leave lasting evidence of human occupation.

We measure ancient changes within the soil using geophysical remote sensing technologies that provide information and enable maps detailing underground archeological features—before (and even without) excavation. These devices work by precisely measuring frequencies and wavelengths of electrical and magnetic energy that comprise portions of the electromagnetic spectrum. Traces of human activities and artifacts remain detectable in the soil hundreds (and thousands) of years after the people that left them have lived and died.

Archaeogeophysical remote sensing is now a fundamental part of archeological investigation. We routinely use multiple technologies such as magnetometry, electrical resistance, electromagnetic conductivity, magnetic susceptibility, and ground penetrating radar to study long-past human activities that have resulted in variations to soil moisture, texture, compaction, burning, artifact composition, and cultural soil enrichment.

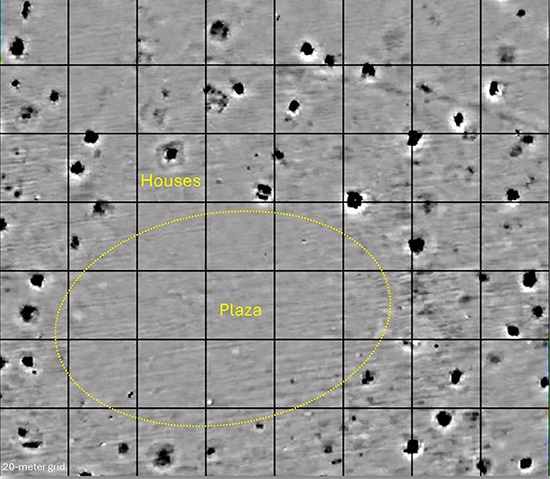

In archeological applications, geophysical data are typically collected at close intervals for a volume of soil at closely-spaced and predetermined locations—often within a surveyed grid pattern enabled by global positioning system (GPS) technology to pinpoint the location of each geophysical measurement collected.

Magnetometry (measured in nanoteslas) detects human changes to the earth’s natural magnetic field and alignment—brought about through cultural activities such as burning, soil movement, introduction of ferrous metals, or other cultural alterations to the soil. Topsoil is commonly more magnetic than subsurface soils, so long-past human actions such as digging and/or heaping are detectable. Anthropogenic burning (i.e., hearths) and firing (i.e., ceramic kilns) change the magnetic strength and orientation (inclination and declination) of archeological features, and these changes are commonly identifiable using a magnetometer.

Electrical resistance (measured in ohms) detects human modifications that affect soil moisture and content, which alters the efficiency with which electricity can be conducted through the ground. For example, archeological features that involve digging, heaping, or soil compaction will conduct electricity either more or less efficiently than the surrounding unaltered soil.

Electromagnetic conductivity data (measured in MilliSiemens) is often compared as the theoretical inverse of electrical resistance. If a material is more conductive, it is less resistant to the flow of electricity. However, conductivity data often contribute unique details due to a different technological configuration and unit of measure.