Dr. Andrew R. Beaupré, Station Archeologist, ARAS-UAPB

Artifact of the Month - April 2021

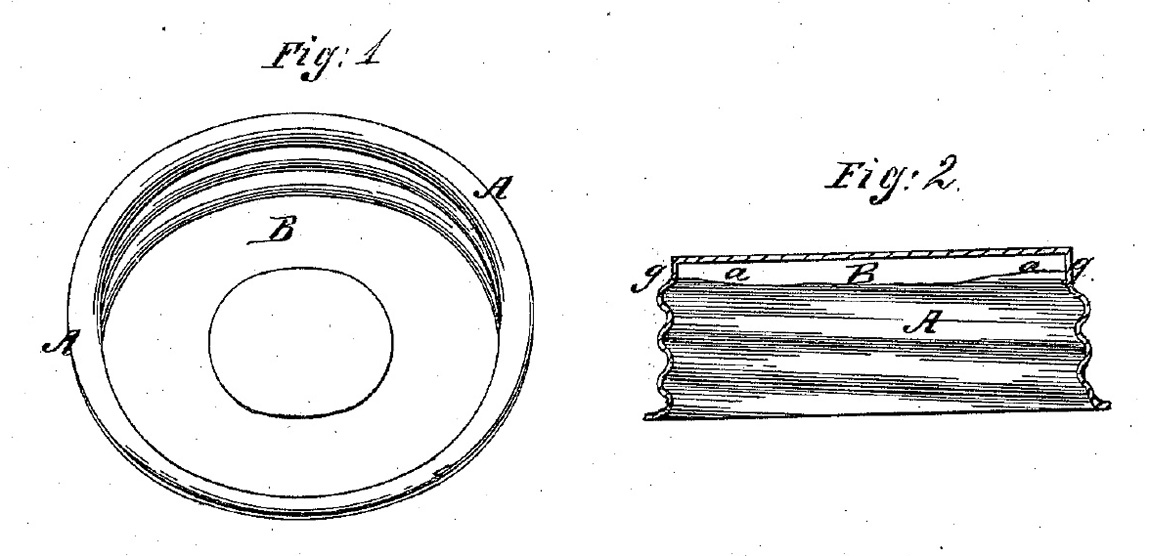

This month’s artifact is a cross-mended glass disc identified as a Boyd’s “Porcelain” canning jar liner. Comprised of 4 shards, the nearly complete artifact is 2.5 inches (63mm) in diameter and 1/8 inch (3.175mm) thick. The profile of the artifact is stepped to allow for an airtight seal to the canning jar. The artifact is embossed with the text, “BOYD’S GENUINE PORCELAIN LINED CAP 16” (Figure 1). A major misnomer associated with the artifact is that it is labeled as if it is made of porcelain; however, the artifact is actually made of a transparent and/or translucent “cloudy” glass categorized by archeologists as opaque white but known colloquially as milk glass (Jones and Sullivan 1985:14). At time of manufacture, the liner would have been fit inside an inexpensive threaded metal cap and rubber O-ring to complete the compound canning jar lid (Figure 2).

By the outset of the American Civil War, commercial canning of fruits and vegetables was commonplace (Cowen 1983:73). Many of these early commercially canned goods were famously tainted, as is often cited as the downfall of the 1845 Franklin Expedition to the Canadian Arctic (Swanston et al. 2018). Parallel to the commercial canning of foodstuffs in metal containers, was the development of home canning in glass jars. In 1854, the now household name of the Mason Company began to manufacture canning jars (Hinson 1996). By the late 1850s, patents concentrated on home canning surpassed those associated with commercial operations in an effort to ensure that the individual household was a center of food preservation (Michaels 2015:22). Historical documentations and archeological evidence indicate that by the 1880s, use of canning jars was synonymous with both urban and rural households as well as small cottage industry outlets such as lumber camps (Howe 2015; Michaels 2015; Cowan 1983; Strasser 1982).

Prior to the invention of the liner, circa 1869, canning jar lids were made either entirely of glass or entirely of metal (Boyd 1869). Until Henry Putnam of Bennington, Vermont invented the modern glass lid and “lighting closure” system in 1882, the glass lids available were expensive to manufacture and not suited to creating an airtight seal (Hinson 1996). Therefore, most people opted for the entirely metal lids that all closely followed Mason’s (1858) patent comprised of zinc metal cap with a rubber sealing ring. While sufficiently cheap, the zinc lid system lacked a buffer between the metal and food, giving the food a “quite perceptible taste” (Boyd 1869). Boyd’s liner system retained the cheap screw-top zinc cap but placed the glass liner between the metal and food, ensuring that only glass ever touched the food (Boyd 1869). Boyd’s design was present in home canning operations through the turn of the twentieth century. Over the term of their manufacture, several different styles of these “porcelain” lid liners were produced by Boyd and other companies.