Larry Porter, Arkansas Archeological Survey/WRI Station

Artifact of the Month – November 2020

Fishing has traditionally been a popular recreational, subsistence, and commercial activity in Arkansas dating back far into antiquity. Well before the rod and reel and bass boats of today, ancient Native Americans were employing surprisingly familiar subsistence fishing methods. Artifacts that archeologists recognize as being related to fishing are occasionally found on sites in Arkansas and elsewhere. Bone and sometimes shell fish hooks are found on sites with good faunal preservation. Cordage and woven nets, usually made from plant fibers, are rarely found except in extremely dry environments such as the dry bluff shelters of the Ozarks. Probably the most common and perhaps most overlooked non-perishable fishing-related artifact is the notched stone net sinker or weight. They appear in lots of collections but not usually in the quantities one would expect considering the fairly large number of sinkers/weights that would be required for a net of any size and the long time period over which they were used. They are possibly often overlooked because of their nondescript nature. They are not “flashy” artifacts.

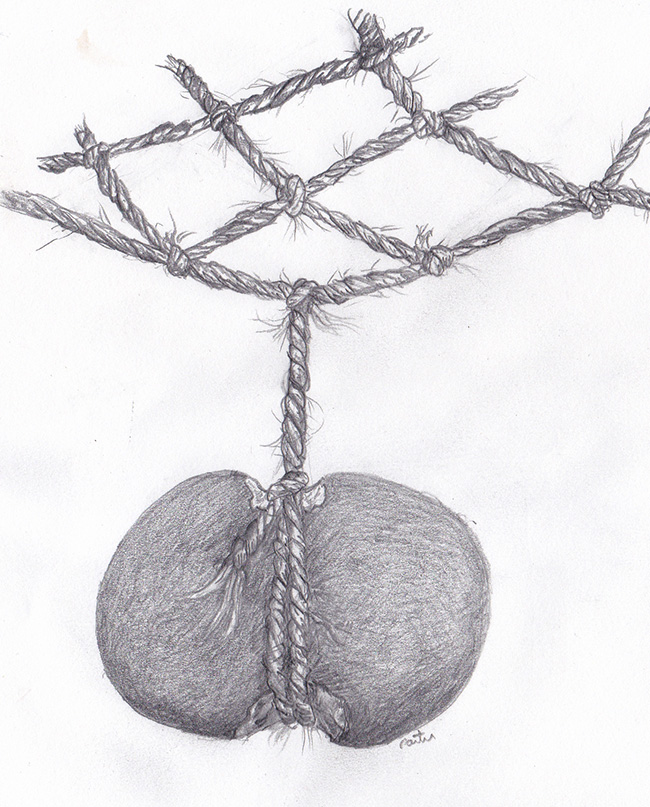

Notched stone net sinkers tend to be small and minimally worked. The only modifications usually consist of two notches, one on each opposite edge of a small, thin, water-smoothed stone (Figure 1). Occasionally they only have one notch if there is a suitable natural concavity on the opposite edge, making these specimens more difficult to recognize. These notches aid in attaching the stones to a gill net (Figures 2 and 3) or hook and line, to anchor the net or line at the desired depth. Although they are usually referred to as net sinkers they could equally have served as weights on a long line with baited hooks spaced at intervals much like the modern “trot line” ( Peacock 1987). Being strictly utilitarian objects, they usually exhibit little, if any, attempt to make them decorative. After all, they probably spent most of their use life under water and out of sight. And if lost during use they could be manufactured and replaced in a matter of minutes.

Notched net sinkers first begin to appear in the archeological record during the Middle Archaic period (6000–3000 BC). This was a period marked by dramatic climate change known as the Hypsithermal or Altithermal interval. It was a time of much warmer, drier conditions that brought about many environmental changes. The upland forests were replaced by a more arid, desert-like landscape (Beckman 1969). With the drier climate major rivers and streams became more entrenched and predictable, creating a new food source to supplement hunting and gathering strategies. Aquatic food resources became more easily accessible making the stream valleys more attractive for settlement (Schambach 2012). This enabled a more stable, sedentary life style (Trubitt 2019). For native peoples these changes necessitated a shift in, or more appropriately an addition to existing subsistence practices, which in turn created a need for technologies adapted to the exploitation of this “new” resource. Thus, the appearance in the Middle Archaic period of fishing and aquatic resource gathering tools to add to the already existing arsenal of hunting and gathering technologies.

The Middle Archaic Period is characterized by a variety of stemmed and notched projectile points. Some examples are Johnson, Big Sandy, Ellis, and Rice Lobed. Other artifacts typical of this time include hafted scrapers as well as stone drills, grooved axes, and notched net sinkers (Sabo et al. 1990; Schambach 2003). A distinctive and fairly well-defined culture of this period is the Tom’s Brook culture, named for a bluff shelter site in Johnson County, Arkansas that was excavated in the early 1960s. The Toms Brook culture was widespread throughout western and southwestern Arkansas. It appears to be particularly prominent in the Ouachita River drainage of the lower Ouachita Mountains region. As an example, over 800 net sinkers were found on a site in the Ouachita River drainage in Garland County (Schambach 1998). Primary diagnostic artifacts of this culture are Johnson projectile points, hafted scrapers made on modified Johnson points, and notched net sinkers. These hafted scrapers, usually thought of as hide processing tools, could also have served as a tool for removing fish scales.

Net sinkers were not necessarily confined to Toms Brook culture but were probably ubiquitous throughout the Middle Archaic riverine-oriented cultures, but they seem to be a predominate feature of Tom’s Brook culture in western and southwestern Arkansas.

Interestingly, notched net sinkers seem to drop out of the archeological record in later periods. Fish and other aquatic species continued to be utilized but apparently not to the extent seen in the Middle Archaic period. Several factors could account for this, not the least of which are probably climate and environmental changes. Major cultural changes often occur, in part, as a response to environmental/climate change (Balter 2010; Wolverton 2005; Munoz et al. 2010). More cultural changes occurred as the Hypsithermal interval began to subside, the climate cooled, and the landscape became more forested. Adjustments were again made to subsistence practices. The focus probably returned to increased dependence on hunting and foraging. Forest resources such as nuts were heavily utilized, as evidenced by an increase in plant processing artifacts such as pitted nutting stones. Additionally, by at least Early Woodland times, horticulture of native plants was being integrated into the diet with apparent decreased dependence on fish and aquatic resources. As an example, faunal analysis of data from excavations of a Middle to Late Woodland period site (3LO226) in Logan County, Arkansas indicated that fish and other aquatic resources (with the exception of a fair amount of mussel shell) were a very minor component of a large and generally well-preserved faunal sample overwhelmingly dominated by deer and other terrestrial species—a somewhat surprising finding considering the site’s location near the confluence of two major streams where aquatic resources would be readily available and abundant (Porter 2016). Additionally, no definite fishing-related artifacts were identified at the site. This could be due to changes in the technology to methods that were not preserved archeologically, such as fish traps and weirs constructed from perishable materials. The introduction of the bow and arrow in the Late Woodland period could also have played a role. Bows used in conjunction with dugout canoes would appear to have been useful in the slow-moving back swamps and oxbows that were extensively occupied in later prehistoric times, especially in shallow water. Also, differential preservation of fish remains versus larger mammal remains in archeological deposits could be a factor.

That fishing was still an important subsistence practice throughout the rest of the prehistoric period is illustrated (literally) as rock art in a well-known bluff shelter site on Petit Jean Mountain (ARAS site files). Two pictographs, attributed to the extensive Late Mississippian occupation of the nearby Arkansas River valley, are an unmistakable depiction of a paddlefish next to what is interpreted to be a fish trap.

Although notched stone net sinkers appear to have been replaced by other fishing methods and subsistence practices after the Archaic period, they remain as an early example of native adaptive technology in response to dramatic environmental changes.

References Cited

Balter, Michael

2010 Did Climate Change Drive Prehistoric Culture Changes? Online document, accessed August 2020, https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2010/12/did-climate-change-drive-prehistoric-culture-change

Beckman, Michael A.

1969 Middle Archaic Complex of Northwest Arkansas. Arkansas Academy of Science Proceedings 2(2010).

Munoz, Samuel E., Konrad Gajewski, and Mathew C. Peros

2010 Synchronous Environmental and Cultural Change in the Prehistory of the Eastern U.S. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. Online document, www.pnas.org/content/107/51/22008

Peacock, Evan

1987 Prehistory of Hunting and Fishing. Reprinted from Mississippi Outdoors Magazine. Online document, http://www.msarchaeology.org/maa/peacock1.pdf

Porter, Larry

2016 Salvage Excavations at the Wild Violet Site, 3LO226, a Woodland Period Site in Logan County, Arkansas. Ms on file, Arkansas Archeological Survey, Fayetteville.

Sabo, George III, Ann M. Early, Jerome Rose, Barbara A. Burnet, Louis Vogele Jr., and James P. Harcourt

1990 Human Adaptation in the Ozark and Ouachita Mountains. Research Series No. 31. Arkansas Archeological Survey, Fayetteville.

Schambach, Frank F.

2003 Arkansas History and Prehistory in Review, Tom’s Brook Culture: A Middle Archaic Culture in Southwest Arkansas. Field Notes, Newsletter of the Arkansas Archeological Society (314):9–15.

1998 Pre-Caddoan Cultures in the Trans-Mississippi South. Research Series No. 53. Arkansas Archeological Survey, Fayetteville.

2012 Tom’s Brook Culture. Online document, accessed July 2020, https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/toms-brook-culture-546/

Trubitt, Mary Beth

2019 Archaic Period. Online document, accessed August 2020, www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/Archaic-Period-542

Wolverton, Steve

2005 The Effects of the Hypsithermal on Prehistoric Foraging in Missouri. American Antiquity 70(1). Online document, accessed August 2020, www.researchgate.net/publication/256409728

Collections and items in our institution have incomplete, inaccurate, and/or missing attribution. We are using this notice to clearly identify this material so that it can be updated, or corrected by communities of origin. Our institution is committed to collaboration and partnerships to address this problem of incorrect or missing attribution. For more information, visit localcontexts.org.

Collections and items in our institution have incomplete, inaccurate, and/or missing attribution. We are using this notice to clearly identify this material so that it can be updated, or corrected by communities of origin. Our institution is committed to collaboration and partnerships to address this problem of incorrect or missing attribution. For more information, visit localcontexts.org.

The Arkansas Archeological Survey is committed to the development of new modes of collaboration, engagement, and partnership with Indigenous peoples for the care and stewardship of past and future heritage collections.

The Arkansas Archeological Survey is committed to the development of new modes of collaboration, engagement, and partnership with Indigenous peoples for the care and stewardship of past and future heritage collections.

The TK Notice is a visible notification that there are accompanying cultural rights and responsibilities that need further attention for any future sharing and use of this material. The TK Notice may indicate that TK Labels are in development and their implementation is being negotiated. For more information about the TK Notice, visit localcontexts.org.

The TK Notice is a visible notification that there are accompanying cultural rights and responsibilities that need further attention for any future sharing and use of this material. The TK Notice may indicate that TK Labels are in development and their implementation is being negotiated. For more information about the TK Notice, visit localcontexts.org.