by Juliet E. Morrow, ARAS-ASU Research Station

Named for Frank Sloan of Jonesboro, Arkansas, the Sloan point type is a large, thin biface made sometime between about 12,500 and 11,500 years ago (Figure 1). The Sloan point in Figure 1 is the type specimen which was found at the Sloan Dalton cemetery (3GE94) in Greene County, Arkansas. The site was excavated in 1974 by the Arkansas Archeological Survey. The Sloan point from this world famous site is the widest and longest Dalton biface from the Sloan site assemblage. It is 189.2 mm long, 59.1 mm wide, and 11.1 mm thick. Sloan points and Dalton points were made by hunter-gatherers who moved seasonally across much of the eastern two-thirds of central North America. Many other large Dalton points were also recovered from the Sloan site, but most of these are quite a bit smaller than a Sloan point (Figure 2). The association of a Sloan point with other Dalton points at the Sloan site (3GE94) is the best indicator of this point type’s relative age and cultural affiliation.

Dalton point technology extends from central Illinois to northeast Arkansas and from the western edge of the Appalachians to central Oklahoma. So far, Sloan points have been found primarily in states bordering the Mississippi River.

Sloan points are not simply large Dalton points, they are unusually large or “hypertrophic” hafted bifaces that probably had symbolic meaning. Sloan points are much wider and longer than the average Dalton point and their overall outline shape is parallel-sided to triangular. The basal concavity is comparatively shallow and the flaking pattern is typically collateral to the midline of the biface over transverse percussion with pressure thinning (see Morrow 1996). They resemble some smaller Dalton points in their overall shape and flaking pattern (Figure 3).

At least two dozen other Sloan points have been found in the Central Mississippi Valley. Most of them are made of white chert that may derive from the Burlington Formation; however, large cobbles of Burlington chert also occur in the Pliocene Upland Complex Gravels of Crowley’s Ridge in northeast Arkansas. Dalton people may have preferred Burlington chert because of its color, high quality, and knappability. Knappability refers to the ease with which the stone could be chipped to a desired shape. Research shows Dalton knappers may have preferred white cherts like those from the Burlington and Penters Formations not only for their knappability but also because they were available in large piece sizes. Highly mobile hunter-gatherers selected large piece sizes to make large tools because they have longer use-lives. When large tools break, the fragments can be recycled into new tools. Large tools are like an insurance policy. If a large tool breaks, many kinds of serviceable tools can be made from the fragments. For mobile hunters scattered widely across the landscape, large tools would be better than small tools because of the uncertainties involved in obtaining flint. Sloan bifaces are probably a hold-over from the Clovis era when hypertrophic bifaces were routinely made and cached for future use and also placed into graves, perhaps offered to the gods or spirits. Sloan points may be a material expression of the notion that Dalton groups in different regions could rely on each other in hard times. We know from the archeological record that Dalton foragers gathered, perhaps annually, at special places where Sloan points and other hypertrophic Early Archaic period bifaces have been recovered.

Sloan points, as well as other very large bifaces, have been regarded as ceremonial objects but in addition to any ritual purpose or purposes they served, they were also useful tools. If they were used, either by Dalton people themselves, or by later groups, we don’t yet know for what specific tasks they were used or the type of material on which they were used. None of the reported Sloan points exhibit impact fractures so they probably didn’t function as spear points. Bones of cervids (elk and deer), fish, and birds recovered from several Dalton sites indicate people were hunting and fishing. Easily processed plant foods like nuts and berries were probably also part of the Dalton diet based on the few professionally excavated Dalton sites where samples of floral and faunal remains were recovered during controlled excavations. It’s unlikely, however, that Sloan points were needed to process any of these foods.

One of the reasons why I think Sloan points were possibly used as knives is based on a study I conducted in 2010. I designed a series of experiments using replicated Dalton points on a variety of animal tissues (bone, skin, flesh) to create use-wear that might approximate patterns observed on the Dalton points from the Sloan site (including the Sloan point). Under low power (40 to 130x) I compared use-wear traces on the replicas to the use-wear traces on the Dalton points. I observed polish on the lower portion or haft area as well as rounded and polished lateral margins of the biface blade on the Sloan point (see Figure 1). It is possible, but not likely, that this point was not used and the traces may instead represent manufacturing traces.

Another reason why I think Sloan points could have been used as knives, but not necessarily by the Dalton people who made them, is evidence of knife wear on three probable Sloan point fragments. These include two large point fragments donated to the Survey by two different collectors. One was found near Egypt, Arkansas; it’s made of a white chert that could be from the Burlington Formation or from the Pliocene Upland Gravels, the nearest source of which is Crowley’s Ridge. The second fragment, made from Pitkin chert, was found in Mississippi County, Arkansas. The Pitkin example exhibits surface fractures suggesting it’s been heated, but not necessarily by Dalton people. The third probable Sloan point is also from Mississippi County, Arkansas.

Other Sloan Points

Another Sloan point from Arkansas was found long ago near the town of Fisher. At the time it was in the Floyd Ritter collection, Pete Bostrom made a cast of it (Figures 4, 5, and 6).

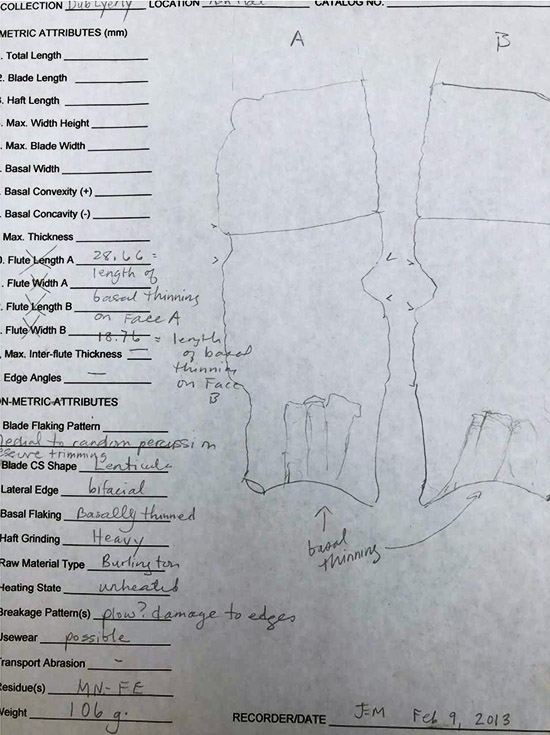

In 2013, I documented a very large biface that was found on a terrace of an old slough in Dunklin County, southeast Missouri (Figures 7 and 8). Like Sloan points it is made of Burlington chert, it’s heavily ground along the lateral margins, and appears to have use-wear traces. The haft grinding and the outline form suggest that it’s not a Sloan point, but rather a very large Dalton point. The ability to reexamine an artifact periodically allows you to see and learn more than if you examine it on only one occasion. It took me three trips to Montana to feel confident about the data I collected on the Anzick artifacts and I’m sure that if I saw them again, I’d see things I hadn’t noticed in 1999, 2000 and 2001.

A recent Sloan point I photographed is from site 11AX267 in Alexander county, Illinois where a number of hypertrophic bifaces have been found (Figure 9, above). It’s a truly spectacular specimen. I have not measured it but as you can see by the scale in the photograph it is over 300 mm, maximum blade width is 87.4 mm, and base width is 72.8 mm.

One of the reasons for my current focus on Sloan points is my curiosity about the Dalton culture and technology. Stylistically, it’s very different from Clovis, Folsom, and Gainey and other Paleoindian stone working technologies, but organizationally, Dalton stone working technology is not all that different from their ancestors. Their technology was designed to help them gather resources that would help them make it through the winter, ensure that they kept in contact with their kin in other regions, and find suitable mates. With Sloan points, they appear to be propitiating the spirits by burying them ceremoniously at special places like the Olive Branch site. This propitiation may have been practiced in accordance with a seasonal round that brought people from different regions together at sacred places on the landscape when certain heavenly bodies such as planets, stars, constellations, and galaxies like the Milky Way were in observable alignments.

More about Sloan from the Arkansas Archeological Survey

The Sloan Site (50 Moments in Survey History)

The Sloan Point from 3GE94 in NE Arkansas (Artifact of the Month series)

The Sloan Site Photo Gallery - a supplement to the 2018 reprint of Sloan: A Paleoindian Dalton Cemetery in Arkansas by Dan F. Morse

References for Additional Reading about Sloan points and Dalton Culture

Morrow, Juliet E.

2016 Clovis Evidence for Paleoindian Spirituality and Ritual Behavior: Large Thin Bifaces and Other Sacred Objects from Clovis and Other Late Pleistocene-Early Holocene Cultural Contexts. In Research, Preservation, and Communication, Honoring Dr. Thomas J. Green on his Retirement from the Arkansas Archeological Survey. Research Series 67:18–65. Arkansas Archeological Survey, Fayetteville.

2010 The Sloan Dalton site (3GE94) Assemblage Revisited: Chipped-stone Raw Material Procurement and Use in the Cache Basin. The Missouri Archeologist 71:1–40. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/18262867/The_Sloan_Dalton_Site_3GE94_Assemblage_Revisited_Chipped-Stone_Raw_Material_Procurement_and_Use_in_the_Cache_Basin

The Dalton Culture http://www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net/encyclopedia/entry-detail.aspx?search=1&entryID=545

1996 The Organization of Early Paleoindian Lithic Technology in the Confluence Region of the Mississippi, Illinois, and Missouri Rivers. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, Washington University, St. Louis.

Perino, Gregory

1985 Selected Preforms, Points and Knives of the North American Indians. Volume 1. Points and Barbs Press. Idabel, Oklahoma.

Morse, Dan F.

1997 Sloan: A Paleoindian Dalton Cemetery. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

Morse, Dan F., and Phyllis A. Morse

1983 The Archaeology of the Central Mississippi Valley. Academic Press, New York.

Stuckey, Sarah D., and Juliet E. Morrow

2013 Sourcing Burlington Formation Chert: Implications for Long Distance Procurement and Exchange. The Quarry #10:20–29.