The Jonesboro research station is located on the Arkansas State University campus, where the station archeologist teaches in the Department of Criminology, Sociology, Geology and Social Work. The ASU research station territory includes 15 counties of northeastern Arkansas. American Indian cultural development from 12,000 b.c. to historic times and early Euroamerican settlements are represented in the archeological record. Among the well-known sites are the Dalton period Sloan site—the oldest known cemetery in North America—and the King Mastodon, which was featured in National Geographic magazine. A large number of sites date from the scientifically critical transition that occurred about 10,000 years ago between the Ice Age (Pleistocene) and modern (Holocene) climatic regimes. Geographically, the ASU station incorporates the eastern border of the Ozark Plateau and the vast lowland areas of the Mississippi River basin and its tributaries. Station territory thus provides ideal natural laboratories for the study of diverse adaptations in Arkansas prehistory.

Juliet Morrow (Ph.D., Washington University in St. Louis, 1996) is the Survey’s Research Station Archeologist for ASU/Jonesboro, and Research Professor of Anthropology, University of Arkansas – Fayetteville. Prior to joining the Survey in 1997, she had a position with the Office of the State Archeologist of Iowa’s Highway Archeology Program, and worked for various private research firms and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Morrow’s background in earth sciences provides expertise in geoarcheology, geomorphology, and site formation processes. Much of her archeological research has focused on the Paleoindian period and multidisciplinary studies of hunter-gatherer lifeways, stone tool technology, and Pleistocene/Early Holocene ecology.

Sarah Stuckey (B.S. in Physics, Arkansas State University, 2013) was hired as station assistant in January 2014. She had worked as a volunteer at the ASU station for several years. Her Capstone project, under Morrow’s direction, explored the use of FTIR (Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy) for sourcing Burlington chert, an important lithic raw material that was quarried from many locations.

Contact Us

Dr. Juliet Morrow, Station Archeologist

(870) 972-2071

Email: jemorro@uark.edu

Sarah Stuckey, Archeological Assistant

Email: sdstucke@uark.edu

(870) 972-2071

HIGHLIGHTS

Research

-

What is a Sloan Point?

-

Points Formerly Typed as Sedgwick “PFTAS”: A New Point Type for Northeast Arkansas

-

Dr. Julie Morrow's published research on ResearchGate and on UARK.ACADEMIA.EDU

Unique Artifact

From station archeologist Julie Morrow:

From station archeologist Julie Morrow:

I recorded this Mississippian artifact in 2015 during artifact identification day at Parkin Archeological State Park/ARAS-Parkin Research Station. It is a perforated ceramic disc that was made from a sherd of a broken pottery vessel. I think that people began making these around the same time they started processing maize into hominy. Until 2015, I had not seen a ceramic disc that was incised/engraved with a “motif” or design. These ceramic discs are usually tempered with bits of burned shell and they are fairly abundant in the Central Mississippi Valley (CMV) and beyond from at least A.D. 700 to 800 until sometime before Europeans arrived. Possibly used as spindle whorls for spinning vegetable fiber, as bottle or funnel stoppers, and as gaming pieces for a game called “blanket toss” these perforated ceramic discs are multi-functional tools and could have been ornaments as well. They could have served as a part of a composite lamp system for burning bear oil. This example is broken, yet it still provides information about the people who made it, used it, recycled it, used it, and then discarded it at an archaeological village several thousand years ago, south of Jonesboro, Arkansas. This small baked clay piece is a classic example of what’s known as “upcycling”. Upcycling is when you take some trash and use it make something even more valuable to society.

Prairie Cemetery, Craighead County, Arkansas

-

Work Day at Prairie Cemetery (February 2017)

-

"Reclaiming a place of rest: Volunteers work to restore dignity at old cemetery" by Nan Snyder. In Delta Crossroads, Spring 2017, pp.119-122. http://www.deltacrossroads.com/

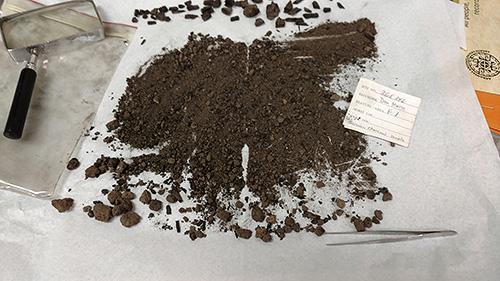

Botanical Samples for C14 Dating

At the ASU Station we are currently selecting charred botanical samples for C-14 dating as part of a long term project on the development of Mississippian-related communities in the Western Lowlands of Arkansas from A.D. 700-900 to 1350. The selection of samples is time-consuming because the context has to be evaluated on a sample by sample basis. Using field notes and other records, in combination with analyses of ceramics, we hope to date at least several more contexts at previously undated Mississippian-related Western Lowland sites. For those unfamiliar with the process of the C-14 method, the first step is to identify to the lowest taxonomic level possible the material to be dated, whether it is wood charcoal, seeds, rinds, nutshell, animal bone, or other organic material. After the material is identified by a specialist, we try to use the smallest amount possible so that the remainder can be preserved for the future. It is possible that there will be improvements in the radiocarbon dating technique as this occurred in the early 1980s with the advent of Accelerator Mass Spectrometry. But it is also part of the general preservation ethic in archeology to save a remainder for future archeological research. We try to preserve for the future, some sites, features, artifacts, and the material remains that are not modified directly but are part and parcel of the archaeological record, that is the remains of meals (animal bones and plant remains) and many other activities. Analysis of plants and animal remains, in concert with other datasets, can help us create a more accurate picture of the past.

Save

Richards Bridge (3CT11)

For the Richards Bridge site, Julie Morrow designed a strategy to gather information about the occupational history of the largest feature at the site. She briefly examined the feature in 2015 and thought it might be a borrow for the mound that once stood to the north of the site. After detailed observations in 2014, it appears that the feature was still in use during the historic period. Based on exposures examined in June 2016, her working hypothesis is that it may be an area where Euroamerican animals like horses, cows, and/or pigs were corralled. This project is a collaboration between the Arkansas Archeological Survey and the Arkansas Archeological Society.